The Dark Road tells us the story of Meili, a young woman from the Hubei Province in China. Her story is told against the backdrop of the one child policy in China. It is the story of one woman and her constant battle for her right to exist on her own terms against a husband and the state both of whom wantonly place demands and regulations on her womb and her body.

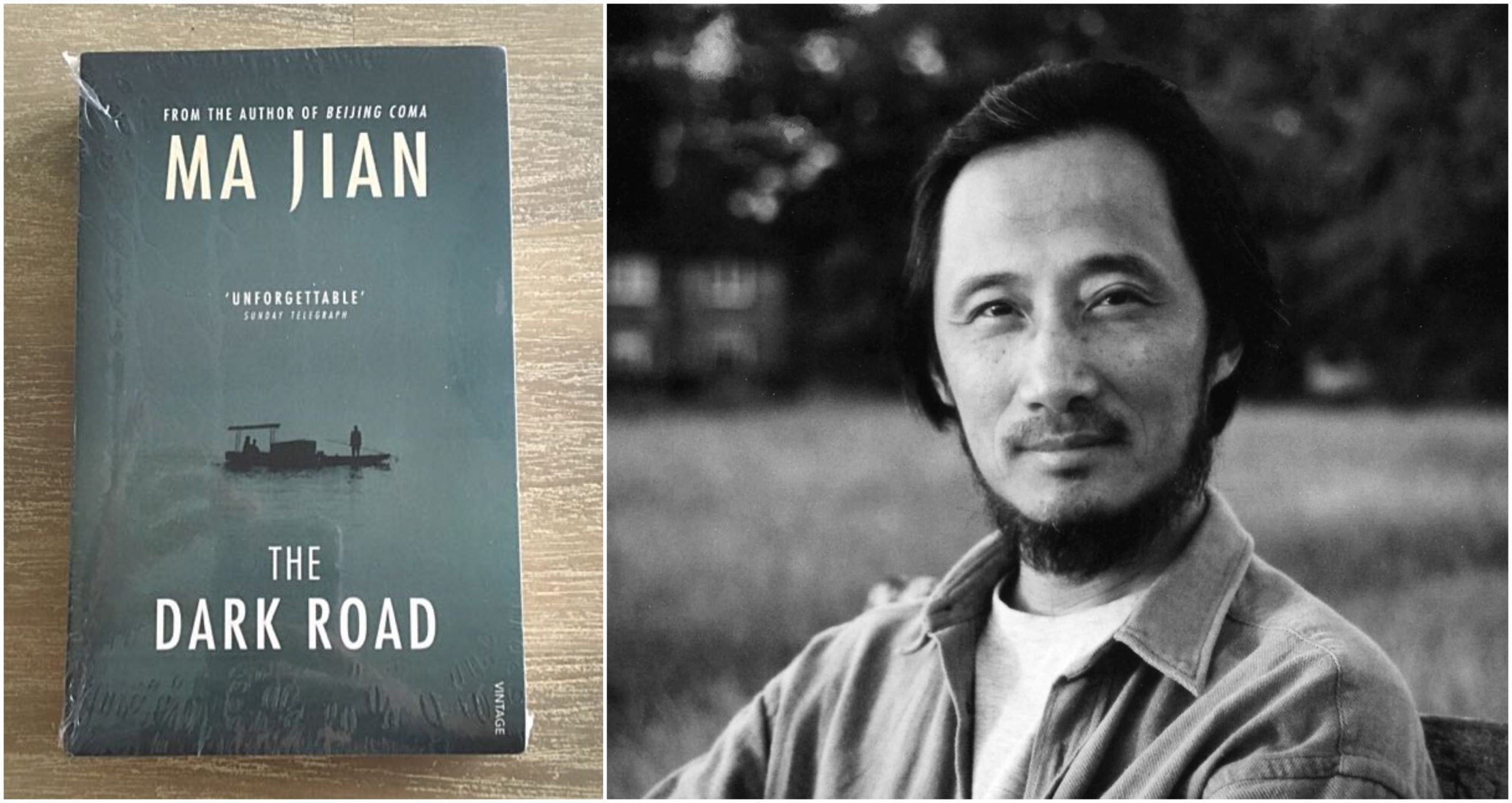

The Dark Road

Author: Ma Jian

Translator: Flora Drew

Genre: Fiction

Publisher: Penguin Press HC (2013)

It has been 35 years since the one-child policy was first implemented in China. It is reported to have prevented up to 400 million births. Introduced by Deng Xiaoping, the goal of the policy was to ensure that population growth did not overtake economic growth. Family planning departments were established at every level of government from villages up to national government branches. Rigorous propaganda paired with heavy surveillance and brute force was employed by the state to ensure compliance to the policy. The Dark Road gives us an account of this brute force.

The term “family planning is met with contempt and fear. And for good reason too. Slogans that are intended to instill fear have been painted on random walls, abortion and sterilisation are doled out at the slightest suspicion and those who are unable to pay the fine for an unauthorised pregnancy have their houses destroyed and their livestock taken. Dead foetuses have become so commonplace that they are either found floating in rivers along with garbage (and other dead bodies) or find their way to the kitchen of cantonese restaurants where they are served in soups to wealthy men. However, what exacerbates the extent of this violence is the cultural preference for a male child. Most women are forced into a second, third and even fourth pregnancy in anticipation of a boy.

Family planning departments were established at every level of government from villages up to national government branches. Rigorous propaganda paired with heavy surveillance and brute force was employed by the state to ensure compliance to the policy. The Dark Road gives us an account of this brute force.

These are facts that any paper or documentary on the One Child Policy could tell you. Jian however gives us a personal account of a woman who is forced to endure the violent consequences of this policy at the behest of her husband. Having had the ill-fortune to give birth to a girl on her first try, Meili is dogged by her husband Kongzi to keep giving birth until they hit jackpot – a male heir that will continue his bloodline. However, family planning officials have started cracking down on their village, and women were being dragged off to administer abortions.

Fearing what this would mean for their unborn child, Kongzi makes arrangements for their little family to sail along the Yangtze River until Meili gives birth to a boy. What ensues is a nine year long journey along the Yangtze River as they dodge family planning officials and live out their lives as migrant labourers scavenging for work to keep their family afloat. Their journey comes to an end in Heaven Township – a riverside community that makes its living off the waste produced by western technology.

The beauty of The Dark Road is that, Jian does not mince his words. He casts a brutal and unflinching gaze on the plight of women and additionally the peasant community in China. The one-child policy acts as the backdrop for this story, but he also reminds us that such policies do not exist in isolation. Jian talks about communities that are alienated by the state in the name of economic empowerment. As the landscapes of China are demolished to accommodate modernity, its rivers face the brunt of this toxicity. Jian draws our attention to those communities – mostly migrant labourers – who negotiate their way around the toxicity to find means of survival. This may mean drinking water rife with parasites, bathing in water that smells like burnt plastic, selling and consuming counterfeit products like mouldy rice milled with wax and soy sauce made from fermented human hair.

Also read: Book Review: Colour Matters? By Anuranjita Kumar

At each stage of Meili’s life, from childhood to a smart 28 year old woman, she forms connections with the women around her, and draws strength from them to give her the push to pursue her dreams. By introducing us to these women, and fleshing out their characters – as infants born of the wrong gender, as unwanted babies and young girls who are nabbed and trafficked, as women who are prosecuted and violated for pursuing sex work, as mothers who are forced to meet their destiny as vessels for their community’s single minded desire for a son, as an old woman who is denied a quiet burial by the state and so on- Jian tells us of the profusion of violators that a woman might encounter in her lifetime.

The beauty of The Dark Road is that, Jian does not mince his words. He casts a brutal and unflinching gaze on the plight of women and additionally the peasant community in China. The one-child policy acts as the backdrop for this story, but he also reminds us that such policies do not exist in isolation.

The Dark Road is neither set in dystopia nor can we put it down and go on with our lives with an offhanded acknowledgment of the “plight of women” in China. Meili’s story is just another one in a long list of stories from around the world, and from the communities of our own country (and the women of those communities) that find themselves at the sharp end of government policies and developmental regimes that fail to take in or are dismissive of the cultural milieu in which they are implemented.

China repealed its One Child Policy in 2015 citing an imbalance in their sex ratio, an ageing population and a drastic drop in birth rates /fertility rates. However, it seems that very few have learnt from China’s lessons. Population growth has always been a concern in India, and while several NGOs and activists actively pursue the matter of family planning, and sensitisation against sex selective abortions, Prime Minister Narendra Modi expressed the need to address India’s growing population numbers in 2019.

Since then RSS Chief Mohan Bhagwat and BJP leader Ashwini Upadhyay have both argued for a population policy that penalises individuals with more than two children, and more recently, senior advocate and Congress leader AM Singhvi is planning to introduce a legislation to foster a two child policy for the country. This bill calls for a number incentives and punitive measures to ensure compliance to the law including penalties in taxation, employment and education. States like Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Assam already discourage individuals from having more than two children

Also read: Book Review: These Hills Called Home: Stories From A War Zone By Temsula Ao

A two-child policy implemented in India – a country that lords the male child over all else – stands to be just as destructive as China’s one child policy. It would bode well for the government to focus on improving socio-economic factors across the country rather than thoughtlessly instilling fear in people over the growing population.

About the author(s)

Krishna has a masters degree in Development Studies from Azim Premji University, and hopes to establish a career in psychology and counselling. She currently resides in Kochi and is taking time out to recharge - physically, mentally and intellectually. Any suggestion that will aid the recharge process will be received with gratitude and excitement.