Motherhood should be a choice, made by those who are autonomous to decide on what may be the best route to parenting. But the overarching patriarchal system has made motherhood a burdensome obligation demarcated for rigorous routine and duty. Being a parent has been historically a challenging domestic role in spheres that have calculated virility as the price of a woman’s worth. And such hyper-gendered roles have become a regurgitation into how invisible mental health issues are in childbirth and parenting.

As we go into a more muted form of celebrating mothers’ day given the current pandemic, I thought to myself why not revisit the popular myths of motherhood. And one of them is the consistent generational push for ‘happiness in being mothers’. Sadly, the reality is not the same. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), around 22% of India’s new mothers suffer through postpartum depression (PPD) after giving birth. In the wake of new maternal health reform where the country has seen a decline in maternal mortality, we need to build a capacity to aptly approach postpartum depression which is becoming more evident in women. And if left unattended, it may cause long term chronic behavioral and psychological struggles.

Because culturally motherhood has been endorsed to prove self-worth and fulfillment for women, we have developed a hazardous environment for child bearers who become naturalized to reproducing rather than retrospecting on their availability to nurture or even to have second thoughts on their choices. Being a mother has made an ornamental gain in our lives while navigating our own agencies. This becomes an insular lifestyle for new mothers who are caught up in the traditional, stifled roles of perennial caregivers to infants while also tending to being in domesticated narratives.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), around 22% of India’s new mothers suffer through postpartum depression (PPD) after giving birth. In the wake of new maternal health reform where the country has seen a decline in maternal mortality, we need to build a capacity to aptly approach postpartum depression which is becoming more evident in women. And if left unattended, it may cause long term chronic behavioral and psychological struggles.

This also brings us to question the socio-cultural factors that have bred this conclave of motherhood in India. Being mothers has always been a symbol of ‘success, stability and bliss’ and ultimately puts undue pressure on mothers who are burdened by financial circumstances, domestic abuse and a history of unhealthy relationships. I think if we are to celebrate mothers’ day to show respect to all the individuals out there who have borne children, the patriarchal standards of child bearing is perhaps a little untoward to the current generation of would-be new mothers who are exploring a variety of options.

Also read: Post-Marriage Depression: The Under Diagnosed, Untreated Reality

As we see a deepening bandwidth of famous personalities coming out with their stories of postpartum depression, or experiencing ‘pregnancy blues’, there needs to be a growing humanization of the struggles new parenting or motherhood carries. But sometimes, young mothers are faced with a hill of challenges in the millennial era that is strife with quests of productivity and material driven accomplishments. Motherhood is now seen more as an inclusive term for care and parenting, not as much as fulfilling dutiful lineage or potency norms.

So while we are committed to embracing change in new age love, marriage, family and parenthood, we should take a more serious look into maternity mental health and how it may cost us a lot in the long term future. Society has invariably romanticized motherhood and distanced its moral chores on the ground to grand baby showers and naming ceremonies so popularly seen on screen. Yet, very little has been done to elevate the sentiments of loss, fatigue, responsibility and guilt that new mothers often experience in the shadows of their bodies becoming shrines of fertility.

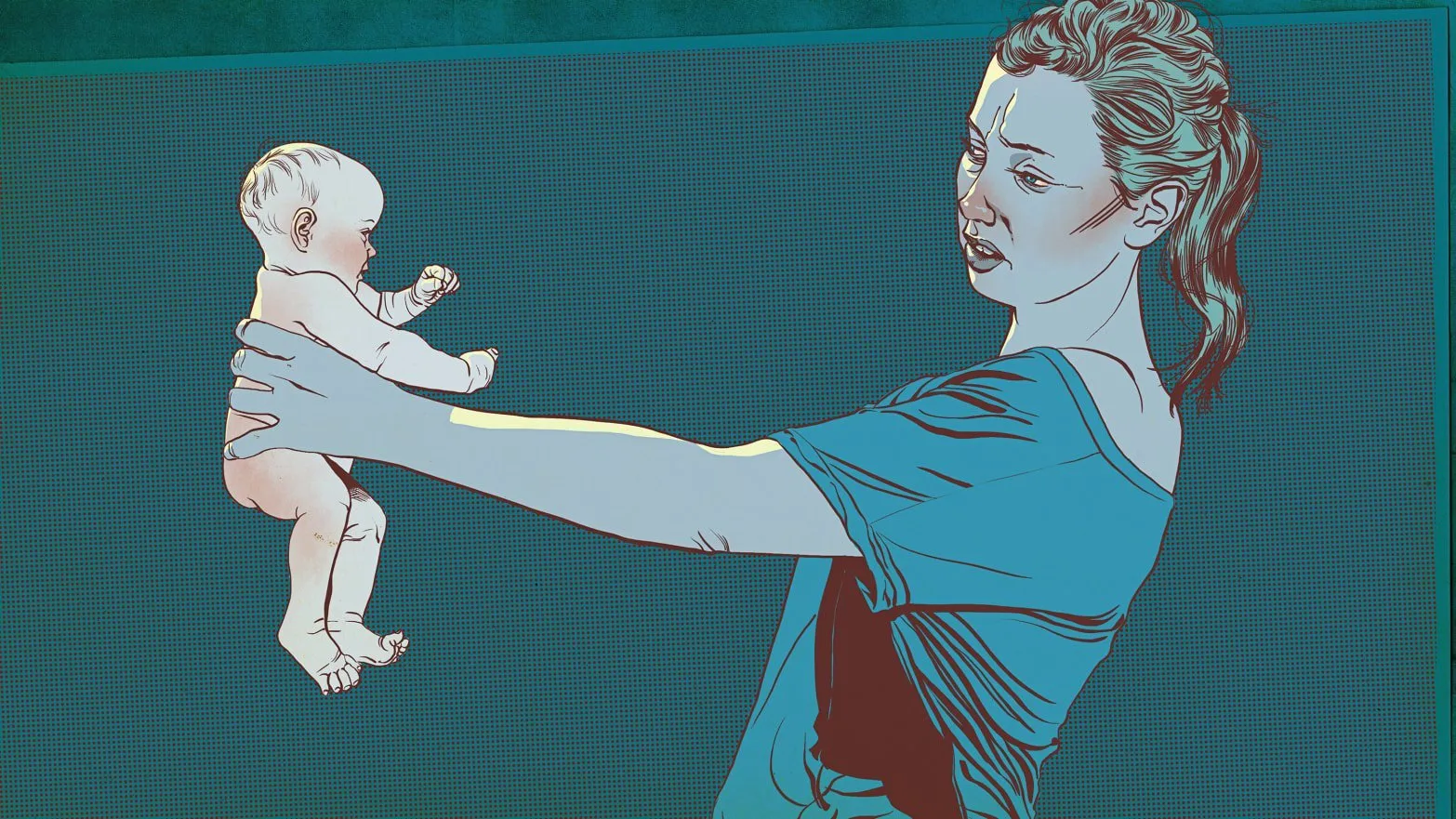

In PPD or postpartum depression, we see new mothers ache in isolation and refusing the supposed comfort and joy in their baby that is almost always found by others. It is not that she doesn’t want her child but at that point, her natal experience or just even becoming a new mother is daunting, exhausting and overwhelming.

Motherhood has been more advertised as a mythological summary of womanhood than that of individual choice and possession. Even in the wake of mental health of new mothers, we have to refer to policies and laws that are made by men who may not be certain of what mothering may entail holistically. So women’s bodies will always be claimed under remittance just like patches of land or factories. In PPD or postpartum depression, we see new mothers ache in isolation, refusing the supposed comfort and joy in their baby that is almost always found by others. It is not that she doesn’t want her child but at that point, her natal experience or just even becoming a new mother is daunting, exhausting and overwhelming.

Childbirth is traumatic and that is a stand alone point that needs to be present in conversations of motherhood. And rearing a child is more celebrated than preserving feminine individuality. It is ‘radical’ to think about self care during motherhood because we are ingrained to believe we are nurturers who have maternal instincts. I find that insulting to an extent because it ultimately reduces us to being ovaries, ready to bleed and carry. Furthermore, it stigmatizes things like abortion, adoption or sterility, which have generationally shunned to mitigate the terms around which motherhood is acceptable or not.

Also read: Postpartum Depression: Deromanticizing Motherhood

Hence, you need to reach out to someone you may know or have known to be struggling with raising a child or experienced postpartum depression. We need to disintegrate this cultural narrative of motherhood being a standpoint of a woman’s life. Normalize postpartum depression and celebrate the mothers who have sought to carry on despite this. Honour mothers not because we can but we should and would want to, regardless.

Sumona is a Kolkata native, currently living in Cape Town. She believes in intersectional feminism and humanism. She is an MPhil candidate in Justice and Transformation at the University of Cape Town where her research interests lie in social politics of citizenship, minority identity and human rights in the post-colonial paradigm in South Asia as well as international security and public policy. She has Bachelor of Social Science Honours degree in International Relations from UCT.

Featured Image Source: The Daily Beast