Warning: Spoilers ahead. Trigger warnings for mentions of sexual assault, caste violence and transphobia.

What do you imagine when you think of a ‘hero’? I’ll venture that it is an upper class, upper-caste (Raichand/Oberoi), presumably fair skinned and good-looking man. That’s the ‘hegemonic’ ideal of masculinity for you. This is not fixed, but keeps changing depending upon the societal context. Unfortunately, there has been relatively little scholarship on masculinities in India, until recently. In this backdrop, Paatal Lok does multiple things: it represents a range of masculinities going beyond the contemporary romanticized Brahmin hero (Chulbul Pandey, Balmukund Shukla, Chintu Tyagi, etc.), shows how masculinities are molded albeit in a North Indian context, and reflects how popular anxieties about masculinity inform fictional character development.

Paatal Lok is a highly provocative call-out of everything ugly about Indian polity-casteism, communalism, fake news and police corruption. I personally greatly enjoyed it as no Indian show has ever charted such radical territory. However, it is nonetheless important to critique the show from a feminist perspective, given that it forms an important part of the cultural discourse on masculinity, though this analysis is by no means exhaustive.

The premise: A mid-level police officer Haathiram Chaudhary (Jaideep Ahlawat) is assigned to investigate an assassination attempt on a primetime journalist Sanjeev Mehra (Neeraj Kabi). The alleged killers are Vishal ‘Hathoda’/‘Hammer’ Tyagi (Abhishek Banerjee), an infamous gangster; Kabir ‘M’, who is circumcised but refrains from claiming a Muslim identity (Aatif Khan); Tope Singh, a Punjabi youth fleeing caste oppression (Jagjeet Sandhu), and Mary ‘Chini’ Lyngdoh, a transgender woman who is presumably of North East ethnic origin (Mairembam Ronaldo Singh). (Note: I use ‘North-East’ not to clump the seven states as a homogenous category but because the show doesn’t clearly identify which state she comes from).

Paatal Lok is a highly provocative call-out of everything ugly about Indian polity-casteism, communalism, fake news and police corruption. I personally greatly enjoyed it as no Indian show has ever charted such radical territory. However, it is nonetheless important to critique the show from a feminist perspective, given that it forms an important part of the cultural discourse on masculinity, though this analysis is by no means exhaustive.

At the beginning, Haathiram divides the localities of Delhi based on his WhatsApp University knowledge of Hindu scriptures. Obviously, Lutyens Delhi is Heaven, adjoining areas of Vasant Vihar and Noida belong to Earth, and his station, Outer Jamuna Paar is from the Netherworld. Similarly, the protagonists are coded into three categories of masculinity. At the top is Sanjeev Mehra, your typical Savarna liberal elite who criticizes the government from the comfort of his Defence Colony bungalow. At the bottom are the three male accused (and Mary). Haathiram, a frustrated Average Joe trying to earn respect in the eyes of his exasperated wife Renu (Gul Panag) and his bratty teenage son Siddharth, is trapped in between. Paatal Lok contains interesting commentary on these three categories.

Heaven

Initially, the show suggests that Lutyens-bred Sanjeev is a victim of circumstance. You see him as an idealistic journalist whose corporate overlords are penalizing him for exposing corruption. He is trapped in a dead-end marriage to Dolly (Swastika Mukherjee), a frivolous South Delhi socialite with anxiety issues. To escape his disillusionment, he predictably starts an affair with a young employee Sara (Niharika Lyra Dutt). However, as the story progresses, his façade unravels. You see that Sanjeev is the embodiment of the weaknesses of mainstream Indian left-liberal opposition-an ivory tower elitist who is willing to obfuscate the truth for holding on to power.

Further, instead of turning his infidelity into a Bajirao Mastani style contest between the two women; Paatal Lok shows Sanjeev as a weak man who lacks the sensitivity and empathy to cope with his wife’s mental illness and save his marriage. It is only by acknowledging Dolly’s contribution to his life that Sanjeev can redeem the little humanity remaining in his hollow personality (Though there is a very dicey scene where Dolly almost commits marital rape before Sanjeev pushes her away. Writers, just because she is a neglected woman, it does not excuse an attempt to sexually assault her husband).

Hell

…is the most controversial part. Paatal Lok heavily deals with caste politics in U.P. and Punjab. Some might critique the screenplay for being akin to ‘blaxploitation’ inasmuch it shows marginalized characters undergoing extreme brutality for the benefit of a privileged audience. This furthers the popular bias that crimes occur exclusively in rural/underdeveloped areas, amongst ‘backward’ communities. However, it can also be argued that this is the reality of India, and while crime is equally prevalent in urban spaces, there is a different level of violence simmering in the underbelly.

For example, the show heavily borrows from Mirzapur’s success by peppering in a healthy dosage of gender-based slurs and cuss words. In every episode, at least one male character will insult another by references to the latter’s penis size or his mother’s vagina. It seemed gratuitous and a blatant attempt to appeal to the Mirzapur fanbase. But is this an example of fiction glorifying reality, or are the show-makers just holding up a mirror to society? The comments on the recent Carryminati v. TikTok controversy indicate that gender-based insults have almost become a second language for Indian men. Do shows then owe a responsibility to moderate the usage of such language? More importantly, why is it that we focus so much of our aggression towards each other’s reproductive parts?

Paatal Lok heavily deals with caste politics in U.P. and Punjab. Some might critique the screenplay for being akin to ‘blaxploitation’ inasmuch it shows marginalized characters undergoing extreme brutality for the benefit of a privileged audience. This furthers the popular bias that crimes occur exclusively in rural/underdeveloped areas, amongst ‘backward’ communities. However, it can also be argued that this is the reality of India, and while crime is equally prevalent in urban spaces, there is a different level of violence simmering in the underbelly.

Similar questions arise with respect to the depiction of rape. I was somewhat disturbed by the Game of Thrones-esque use of sexual assault to show the dark past of some of the characters. But then, how do you address caste-based violence without accounting for rape? It would have been naïve to assume that Tope Singh’s attempts to resist caste oppression would not be met with retaliation against his mother. The show also adopts a conservative rhetoric towards rape by showing how Tyagi is initiated into a life of crime when his uncle orders the rape of his sisters to settle a land dispute.

As the only son, he avenges his family by viciously murdering his cousins. There is no scope for liberal academic discussions of restorative/reformative justice here. Tyagi’s teacher says, almost proudly, that revenge is considered a karmic duty in Bundelkhand. However, this honor killing doesn’t make life better for his sisters-they are quickly married off to families who consider them ‘used goods’. In this way, you see how the commodification of women destroys their male relatives as well, by drilling in a lifetime anxiety about the need to preserve the family’s ‘honour’.

Standing apart from these two cis-het men is Mary, who faces both sexual harassment and racism on account of her queer and North-Eastern identity. If Tope Singh is the ‘angry Bahujan’ who becomes a threat to his Brahmin girlfriend (similar to the Angry Black Man trope), then Mary is the passive queer victim. Tyagi and Tope Singh as cis-gender men bear at least some active responsibility for their fate, but Mary has no choice but to sob copiously as she accepts whatever punishment is meted out to her.

Interestingly, the most wholesome men in the show are its Muslims. In a subversion of the ‘righteous Hindu man’ and ‘sinister Muslim’ dichotomy, Kabir is the only person who comforts Mary while Tyagi and Tope Singh practice callous detachment. Pertinently, Kabir and Mary are the ones who break most easily under interrogation. It is worth wondering whether this reflects how a ‘good’ Muslim/North Eastern/queer character is one who is ‘feminized’ and ‘weak’, therefore non-threatening to the majoritarian Hindu/cis-gender audience.

Imran Ansari (Ishwak Singh), Haathiram’s Muslim colleague/BFF is somewhat different. Imran patiently listens while his colleagues share conspiracy theories about Muslims, and utter communal slurs. However, Imran resists being slotted as the ‘Good Muslim’, who bears unconditional loyalty to the State. When he is asked to be ‘positive’ and ‘progressive’ while discussing the status of minorities in the country, he is visibly frustrated. Later, he lashes out at Haathiram for expecting him to unquestioningly follow his orders. Thankfully, unlike Sacred Games, Paatal Lok avoids killing off the hero’s minority sidekick/friend to further the former’s character development.

Earth

The champion of the show is inevitably its ‘Earth’/middle-man, Haathiram. Though the show covers left-radical issues, it frames its hero (Haathiram) and anti-hero (Tyagi) in the ‘Narsimha-Hiranyukashyap’ dichotomy from Hindu mythology. Tyagi’s horoscope-telling scene is a direct rip-off from Asur, and he is shown to be the Shiva-worshipping Raavan to Haathiram’s Vishnu avatar. Therefore, while the show highlights the realities of caste and communal violence, it deliberately frames the apolitical, cis-het, soft-Hindutva preaching Haathiram as the central character instead of the other protagonists, so as to not completely alienate the audience.

Haathiram has severe daddy issues, which are replicated in his tenuous relations with Siddharth. In a poignant scene, Renu says, ‘Your father was not angry with you, he was angry at himself. I won’t let you take out your anger on our son in the same way.‘ The show therefore identifies how men inherit, or rather imitate aggressive behavior, from what their fathers and other male relatives exhibit at home. Further, that the aggression displayed by men is often a manifestation of their own insecurities about not being able to conform to hegemonic masculinity.

Haathiram has severe daddy issues, which are replicated in his tenuous relations with Siddharth. In a poignant scene, Renu says, ‘Your father was not angry with you, he was angry at himself. I won’t let you take out your anger on our son in the same way.‘ The show therefore identifies how men inherit, or rather imitate aggressive behavior, from what their fathers and other male relatives exhibit at home. Further, that the aggression displayed by men is often a manifestation of their own insecurities about not being able to conform to hegemonic masculinity.

Siddharth heavily resents Haathiram for enrolling him in a posh South Delhi school, where he is bullied on account of his father’s name (since ‘Haathi’ means elephant). He would rather hang out with his local gang, headed by Raju Bhaiya, who possesses a gun. The scenes with Siddharth and Raju show how juvenile crime often has more to do with young men wanting to seize power which is not available to them, than ‘in-built’ criminality.

Also read: Finding Falguni Pathak, The Queer Icon We Didn’t Know We Needed

When Siddharth spies on his crush Saloni making out with an upper-class jock Arjun, Saloni accuses him of making a video, while Arjun and his friends beat him up in front of the school. This is a telling commentary on how the elite are quick to point fingers at a class ‘Other’ if they suspect him of any transgression of sexual boundaries. It also signifies how pop culture perceives privileged women as being classist in their romantic preferences (Strangely, shows never put men under the scanner for wanting to date only a certain ‘type’ of girl). Siddharth cannot compete with the hegemonic masculinity that ‘Arjun’ symbolizes-fair-skinned, rich, drives a sports car-so the next best alternative for him is to brandish Raju’s gun at his school bullies.

Of course, when Raju’s boss finds out that Siddharth stole the gun, it results in painful consequences. This is when Haathiram has his moment. In a fit of rage, he drags Siddharth from their house to confront the goon. When Renu tries to stop him, he slaps her. This is ironic, because on two previous occasions, Haathiram had called out men who hit their wives. However, this is no Thappad. Renu slaps Haathiram back when he returns home, and the score is settled (Sandeep Reddy Vanga would be pleased).

One would think that this is the death-knell for their dysfunctional family relations. Instead, Haathiram earns the validation he always wanted. Siddharth starts respecting his father. Renu tells her brother that she is tired of putting up with his failed business ventures; though she had earlier defended him in front of Haathiram (This ‘annoying mamaji’ trope reflects the Indian middle-class expectation that a woman should abandon familial ties after marriage, lest they become a liability). She suddenly transitions from a nag into a loving wife who supports Haathiram’s unauthorized investigation adventures. The messaging is clear: it is only through becoming an ‘alpha’ that a man like Haathiram, who lacks socio-economic privilege, can uphold hegemonic masculinity and assert his patriarchal authority.

Also read: Has Elitism Won The Race In Indian Entertainment?

I won’t say more because this will turn into a thesis, but Paatal Lok is interesting to study how our perceptions of gender, religion, caste and class interact to form the ‘ideal man’. The show suggests that the test is simpler than what we think: A man who loves dogs is good. I’m sure there are genocidal dictators who possess pets, but it isn’t a bad idea-how you treat animals indicates how good a human being you are. Maybe that’s what the world really needs!

Megha Mehta is a legal researcher based in Delhi. You can find her on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

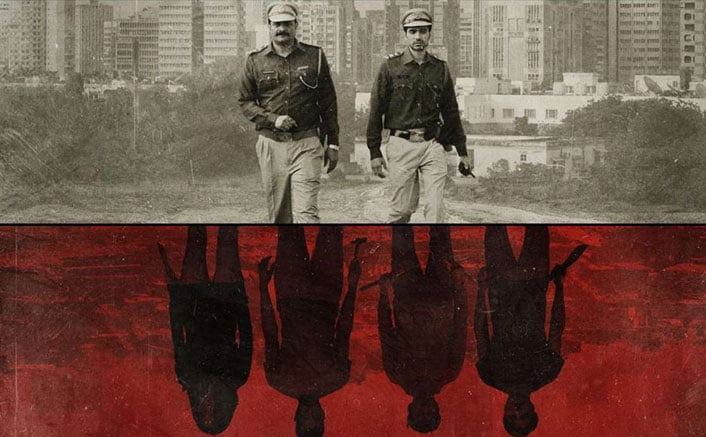

Featured Image Source: Koimoi

About the author(s)

Megha Mehta is a legal researcher based in Delhi.

It’s a mirror to society. Every part of the show is a clear reflection of catsist North Indian khap panchayat mindset and how it screws with people from all castes and walks of life.. Weather it’s upper caste revenge rape of Tope Singh’s mother or Tyagi’s drive to avenge his sisters and their honour.. Wouldn’t change a single bit except see master jis face once..