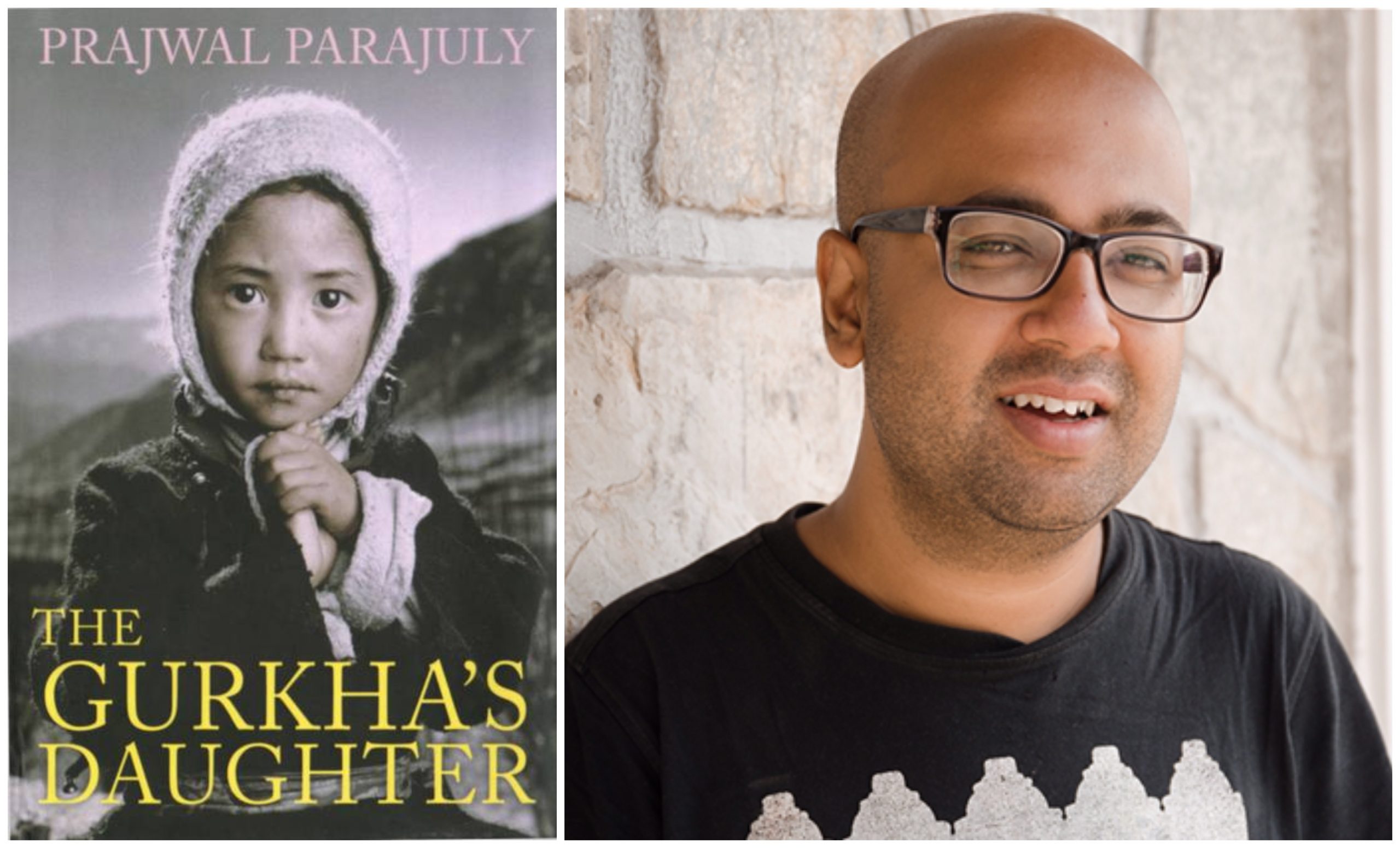

A promising debut, Prajwal Parajuly’s The Gurkha’s Daughter is a collection of 8 short stories. With little purple in the prose, the stories have a beguiling rustic appearance. On better reflection, one can sense strong emotional tinges that, effortlessly, illumine the socio-political milieu of the characters. Highlighting the stark contrasts, Parajuly is an honest-storyteller. He refrains from romanticising about “his world”, blatantly wording biases that plague the Nepali speaking community. Issues of caste, class, religion, and ethnicity are casually brought up, without overshadowing the plot. These stories closely mirror reality, as the narrative implies the normative status these prejudices hold.

The Cleft narrates the story of Kaali, a helper with a disfigured lip. Invested in a codependent relationship with her verbally abusive mistress – Parvati from Kathmandu – she also exchanges letters with a man who promises her stardom, which the reader understands are to cajole her into a life of prostitution. Parvati’s hypocrisies are revealed through the story, where the duo set off to the funeral of Paravti’s hated mother-in-law. Insults like “Adivasi”, “you aren’t good at anything”, “…with a face like that…” and numerous others are regularly flung at Kaali. When her sister-in-law confesses about wanting a divorce or going to college, Parvati tries convincing her to do otherwise, on being a widow herself.

Munnu, in Let Sleeping Dogs lie, is a Bihari “Musalmaan” “paanwala” who is eventually called a “Kukkur” (dog). A shop owner in Kalimpong, Munnu has to deal with Shraddhanjali, the daughter of the “richest lawyer in Kalimpong”, and her shoplifting. Having started from mere toffees, Shraddanjali graduates to stealing expensive colognes in broad daylight. Afraid of losing his job as an outsider, he stays silent. When word reaches the thief’s mother, she attacks his “class” and “religion” for his “false” accusations. In an attempt to quench his burqa-wearing wife’s ambition and find a recourse, Munnu is forced to apologise to his “superior” by putting the blame on his wife, and ultimately hiring her as an apprentice.

A promising debut, Prajwal Parajuly’s The Gurkha’s Daughter is a collection of 8 short stories. With little purple in the prose, the stories have a beguiling rustic appearance. On better reflection, one can sense strong emotional tinges that, effortlessly, illumine the socio-political milieu of the characters. Highlighting the stark contrasts, Parajuly is an honest-storyteller. He refrains from romanticising about “his world”, blatantly wording biases that plague the Nepali speaking community.

Prabin reflects on his relationship with his only daughter, Supriya, and the absence of spousal love in A father’s journey. The reader traverses through tumultuous emotions shared by this “Brahmin” family situated in Gangtok. The onset of puberty, and the practice of menstrual untouchability, leads to an eventual distance between the father-daughter. Nonetheless, they still dote on each other, much to the dislike of the mother. Supriya, despite her strong-willed spirit, conforms to the societal expectations of marrying within one’s caste, despite Prabin’s liberal approach. Echoing his ideals of Brahmin and the others, he, sadly, watches her stick with a “Brahmin” alcoholic.

The psychological turmoil of class-divides is explored in the Missed Blessing. The reader sees Rajiv, a recent graduate, unhealthily, identifying his self-worth with his social status. He feels trapped between caring for his ailing grandmother and putting his cousin-funded engineering degree to use. Pressured to accommodate relatives during a festival, he vents out his frustration by beating his cousin up. He further sours his relationship with the white couple in Darjeeling, vocally suspecting them to have an ulterior motive of converting everyone to Christianity. When his cousins prefer booking a hotel room, Rajiv, humiliated and angry, sees his poverty as filth.

The geographical canvas, ranging from Bhutan to Manhattan, presented before each story does not disperse the common emotional undercurrents. All seasoned with words from the local lingo, The Gurkha’s daughter opens a whole new world for the unfamiliar but feels like coming home for the familiar. Unsentimental, Parajuly unapologetically reverberates the echoes of the mountains that follow even those who try to escape it. Unconscious choices and unfound fears shown by these characters expose the biases harboured even by the best of them.

A beautiful Nepalese-Bhutanese refugee, Anamika Chettri feigns bravado in No Land is Her Land. With two daughters from two failed marriages, despite her roars, Anamika questions her “character” in the same way the rest of the people do. Forced to leave her place due to her ethnicity, she flees Bhutan with the baby of a renegade. Needing security in the camp due to the lurking looks and lecherous comments from men, she decides to remarry. Due to her “inability” to produce a son, she’s sent back to the camp. With the possibility of settling in the States, her abusive husband comes to claim her, threatening to reveal her loose morals. As they pose for a “family picture”, it is revealed that the personal is not akin to the public in her new home.

Also read: What Does It Mean To Be A Tibetan Outside Tibet?

The titular story, The Gurkha’s daughter depicts the friendship shared by the narrator and Gita, whose fathers are part of the British Army. As they mimic their fathers and don fake moustaches, they reveal the post-imperial status of these soldiers. The narrator hoards secrets created out of innocent mischief and guards those of others. It also lets the reader glimpse into the pseudoscience of Hinduism which casts women as “unlucky” creatures due to “dosh” in their charts. Ingrained in the young psyche, the narrator superstitiously tries to distribute to bad fortune to her other friends when Gita leaves.

Passing Fancy is a tale about how a recently retired woman from Gangtok, catches feelings for a fellow morning jogger. With her nest empty, the protective and ever-worrying nature of mothers is played out by the protagonist. As she struggles to get used to the humdrum of being a retiree, the fellow jogger Mr. Bhattarai converses about interesting and almost taboo topics with her. She brings back ideas about nursing homes, alcoholism, gambling, and mental illnesses home, to her husband who brushes them aside. Having realised her predicament, she gets rids of all romance books, as duty rears its ugly head.

While all the other stories are located in the Sub-Himalayan region, the last story takes place in another continent. The Immigrants narrates the story of 2 Nepali-speaking arrivistes in New York. Despite being confused about how one can be ‘Indian-Nepali’, the Nepalese gets along fairly well with the former. The serendipity is ironic, as the narrator goes out to impress someone who looks “rich” but ends up with a maid from a lower class. This well-established person struggling to get legitimate citizenship, hires her, a girl from Nepal who won the green card via a lottery, as a cook in exchange for English lessons. She soon moves in as a roommate, to suggest he marry her for the sake of getting a green card. When he confesses his intention to do so without the suggested motive, she bawls out saying she’s a “servant”.

The geographical canvas, ranging from Bhutan to Manhattan, presented before each story does not disperse the common emotional undercurrents. All seasoned with words from the local lingo, The Gurkha’s daughter opens a whole new world for the unfamiliar but feels like coming home for the familiar. Unsentimental, Parajuly unapologetically reverberates the echoes of the mountains that follow even those who try to escape it.

Also read: Gorkhaland Movement: Have The Gorkhas Been Inclusive Of Their Minorities?

Unconscious choices and unfound fears shown by these characters expose the biases harboured even by the best of them. Flawed traditions and privilege show the weakness of the ignorant upper caste and class, and the damaged self-worth of the marginalised. Parajuly has taken the first step, which is to acknowledge the normalcy of such beliefs, to change. His nomination for Dylan Thomas prize gives hope about how South Asian literature is changing its course, perhaps beyond tokenism.

About the author(s)

Philosophy major with divergent interests, all unified by the need to share her voice and find beauty in the smallest of things.