Indian English Poetry in the 1960’s used the confessional mode to render the ordinary experience in recognisable locations. As Robert Phillips rightly observes,

“Confessional art whether poetry or not, is a means of killing the beasts which are within us, those dreadful dragons of dreams and experiences that must be hunted down concerned and exposed in order to be destroyed.”

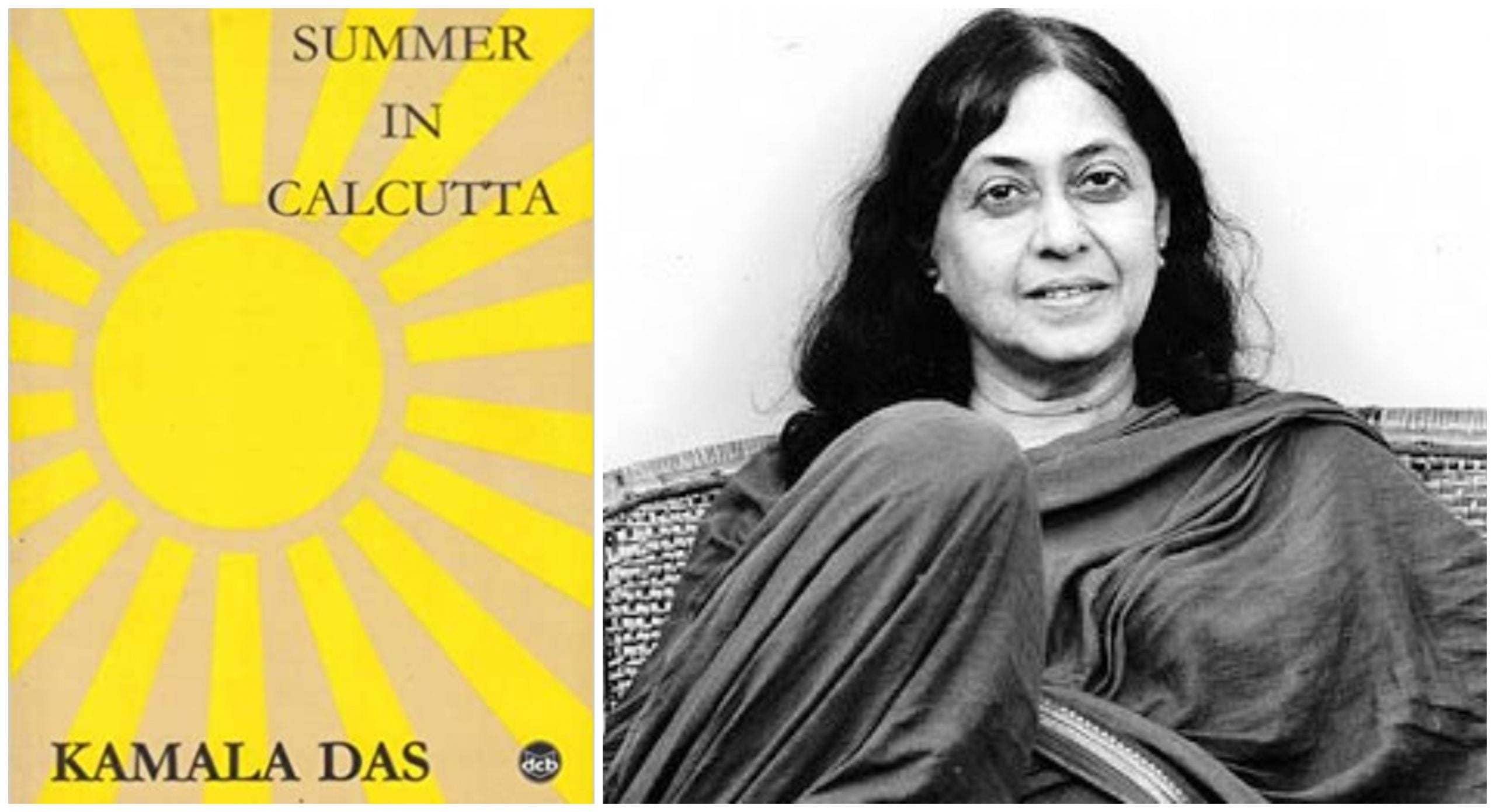

Kamala Das (widely known as Madhavikutty) is one of the pioneer, feminist poets who used the confessional mode in creative and different ways. She published her first collection of poems, Summer in Calcutta in 1965. It was the first of its kind – explosive, bold and assertive in exploring women’s body politics and sexuality like a ‘parcel of dynamite.’ These poems have probably inspired present day feminist poetry more than any other Indian poet – they explode in your face with truths, yet the unraveling of the truth is a subtle, painstaking and emotional process.

Feminist Politics, Identity and Exploration

Kamala Das seeks to explore and slowly peel off, one by one, three layers of politics to locate her identity. The first layer is that of the external – the politics which manifests in public and has implications which are universal. These may be visible power structures as well as invisible hierarchies, that are normalised in the daily course of life but are extremely detrimental to the evolution of the self.

They did this to her, the men who know her, the man

She loved, who loved her not enough, being selfish

And a coward, the husband who neither loved nor

Used her, but was a ruthless watcher, and the band

Of cynics she turned to, clinging to their chests where

New hair sprouted like great-winged moths, burrowing her

Face into their smells and their young lusts to forget

The second layer that she uncovers in her poems is that of the domestic sphere. In her poem, ‘My grandmother’s house’ she is yearning for the lost time and childhood she spent in her grandmother’s home. She associates a sense of security and comfort with that place and is in emotional turmoil for being unable to go back to it. Even the love she feels, is political. She has a deep cynicism towards the domestic idea of love and marriage and she feels that love needs to be de-mythicised and de-constructed. She also indulges in the process of catharsis through this poem.

Also read: Kamala Das – The Mother Of Modern Indian English Poetry | #IndianWomenInHistory

Catharsis is a process wherein you purge out your emotions and seek to address the demons within you. Kamala Das does that brilliantly with her poignant and longing tone. Everyone reading this poem is taken back to a grandparent’s memory and it is a bitter reminder how we have lost out on our childhood and we still crave for the portions of love we received from them. Thus, through this, she may have joined the leagues of Plath and Sexton, because her cathartic poems had a therapeutic effect on the reader as well.

…you cannot believe, darling,

Can you, that I lived in such a house and

Was proud, and loved…. I who have lost

My way and beg now at strangers’ doors to

Receive love, at least in small change?

The third layer she seeks to deconstruct is that of the ‘self’. The confessional mode and nature of her work comes forth through the way she seeks to lay bare her self. Her poetry is emotional, conversational, and it does not explicitly reveal a conscious desire on her part to confess and let her emotions out, in fact the way they unfold is very natural, organic and seamless. The world of power she seeks, lies within her too.

In laying bare the self, or by confessing her emotional turmoil, Kamala Das seeks to do a multitude of things. She has realised the connection between the personal and the political. As women, we seek to internalise power structures, institutionalised ways of oppression and hierarchies within us. Through the confessional mode, Das, (and subsequently we), bring out our self and personal politics, to the public spheres. This, in itself, is a rebellion, since women are not allowed to opine publicly about anything.

Don’t write in English, they said,

English is not your mother-tongue. Why not leave

Me alone, critics, friends, visiting cousins,

Every one of you? The language I speak

Becomes mine, its distortions, its queernessess

All mine, mine alone.

Kamala Das also seeks to question and challenge the heteronormative institution of marriage in the Indian context, which is abusive and oppressive to women. The kind of language she uses in this confessional-rebellious form of poetry is a statement in itself. Language, to her, is not just a means of expression, but it becomes an important tool in challenging the language of men, oppressors and patriarchy. Love, on the other hand, is often packaged as an idea that pertains to the male gaze by falsifying and fetishising the entire idea of womanhood.

Thus, her gendered identity comes through very clearly – as a creative writer and as a young woman raising these questions. Not only is she deconstructing language, she’s destructing and dismantling the language of love too, where she feels it serves the tool of the oppressor. There’s also an underlying exploration of the queer self in her writing. The confessional in her poem An Introduction gives her the space to do both simultaneously.

I asked for love, not knowing what else to ask

For, he drew a youth of sixteen into the

Bedroom and closed the door. He did not beat me

But my sad woman-body felt so beaten.

The weight of my breast and womb crushed. I shrank

Pitifully. Then . . . I wore a shirt and my

Brother’s trousers, cut my hair short and ignored

My womanliness. Dress in sarees, be girl,

Be wife, they said. Be embroiderer, be cook,

Be a quarreler with servants. Fit in. oh,

Belong, cried the categorizers. Don’t sit

On walls or peep in through our lace-draped windows.

Be Amy, or be Kamala. Or better

Still, be Madhavikutty.

Universality and Forging a Collective Feminist Politics

One of the reasons as to why her confessions through her poems is relatable is because of the fact that she places her issues and her own self universally. Whether she talks about oppressive structures of marriage or her discomfort in how she was forced to dress a certain way, she speaks for all women who have gone through similar dilemmas and situations. Her individual pain becomes the community’s pain. Her suffering as a woman, becomes the suffering of womankind in general. Her challenges manifest to reflect the challenges we collectively face on a daily basis.

Also read: Watch: Remembering Kamala Das, The Mother Of Modern English Poetry

When Kamala Das talks about ‘every man’ as an oppressor in her poems, she doesn’t mean all men as individuals are toxic. She believes that men, are symbols of patriarchy and have reinforced certain binaries and stereotypes that oppress women. She collectively sees them as a patronising force who might have been victims of patriarchy, but have benefitted from it more. And thus through her language, words and confessions she appeals for womankind to collectively rise up against these forces that have bound them for eons. She also hopes, that the male readers might get a little empathetic and might do better as men. After all, it is the emotional and intellectual labour that women put in, which makes men realise their oppressive behaviour. (if at all!)

About the author(s)

Imperfect Feminist and Literature Student. Raging to build a kinder world.

Loved reading this poem in class but always Astha’s insights, her words bring out a deeper and newer meaning. Well written, as always!