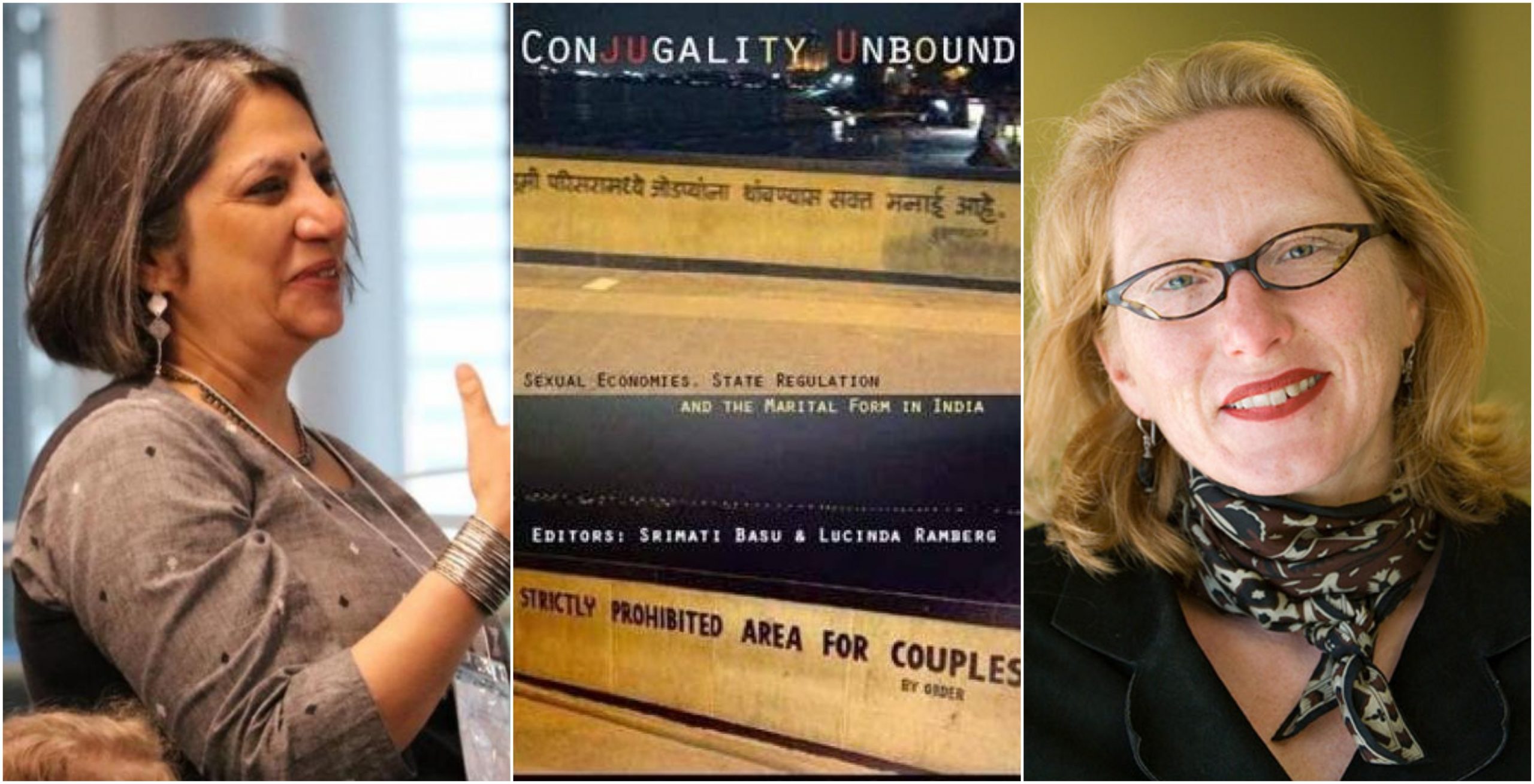

“To all the possibilities and pleasures of conjugal trouble and troubling conjugality” – this is what the dedication page of the book reads, telling the readers in succinct form what is to follow. Srimati Basu and Lucinda Ramberg, both academicians with specialisations in anthropology, gender, women’s and sexuality studies, in their joint work question the dominant understanding of marriage. Conjugality Unbound discusses marriage from three lenses—feminist materialist, post-colonial, and queer theory.

Basu and Ramberg, in the opening essay, engage with the question of what would be a more accurate and inclusive term for referring to the array of unions that people live in. Marriage is a capacious term embracing even non-human alliances (marriage of women to trees, etc.), polyandry, sambandham marriages, temporary conjugal-like contracts, devadasi tradition, etc. Albeit being a fluid term allowing variability, it poses difficulties because of its pervade acceptance. It hails normativity—of heterosexuality and procreation. Marriage denotes an inevitable stage in people’s lives.

This creates and marginalises the other—unmarried people, those in polyamorous or non-sexual relationships, and so on. Marriage accords a superior air to itself. Conjugality on the other hand is not that familiar a term and is thus not burdened with meanings. It is, nevertheless, also a problematic term as it is strongly associated with legal sanctioning and sexual relationships. Conjugality Unbound is informed by existing literature on marriage from Levi-Strauss’s feminist materialist critique that marriage is a practice to build social cohesion among groups through the exchange of women and goods, to Gayle Rubin’s, and Carole Pateman’s view of marriage as a sexual contract that subsumes other forms of being for women- political, economic and cultural.

One can also find the socialist feminist critique of family being at the root of gendered economic subordination. The book has ten contributors who put under examination—conflict, severance, violence, non-heteronormativity and non-reproductivity in unbound marriage and conjugality. It is an interdisciplinary engagement on marital and non-marital relations among individuals discussed in the backdrop of themes of law, governance, religion, caste, kinship, sexuality and materialism.

While all contributors provide necessary critiques of the accepted understandings of conjugality, I’ll discuss two of them at length here.

Prostitution And Marriage, Violence And Choice

Sarah Pinto talks of the confounding intermix of marriage and transactional sex, violence and agency through the story of Lata, a North Indian Brahmin, nineteen-year old, girl. She is going through psychiatric assessment in order to gauge her testamentary capacity. Her mental state is being judged by her moral state whose judgement is based on her sexuality and marital status. Hers is not a straightforward story of absconding for love, even if it is with the domestic help. She runs away with a Brahmin man, Amit, and they live with another man, Faisal. He is referred to as “that Muslim” by everyone except Lata.

The moral status of Lata’s polyamorous marriage is perhaps made worse by the fact that she had relations with a man who was from another religion, thus ruining a potential kinship transaction. She claims to have two husbands with whom she has sexual relations, apart from having sex with other men for money. Amit runs a prostitution ring and according to Lata’s mother, she had been sold to Faisal. One is reminded of Gayle Rubin’s essay, The Traffic in Women: Notes on the “Political Economy” of Sex published in the 1975 collection Toward an Anthropology of Women by R. R. Reiter. She argues that transactional kinship depends on the traffic of women.

Srimati Basu and Lucinda Ramberg, both academicians with specialisations in anthropology, gender, women’s and sexuality studies, in their joint work question the dominant understanding of marriage. Conjugality Unbound discusses marriage from three lenses—feminist materialist, post-colonial, and queer theory.

Lata had escaped from one kind of trafficking, that of a “decent marriage” to get into another. There is an implicit and unwitting critique of marriage in Lata’s story. She is confounding love and marital arrangement, desire and transaction. Her seemingly autonomous agency is reordering gender and dependency. Pinto uses Lata’s story to present a polyvocal polemic against marriage and yet is cautious in calling her a feminist heroine.

An important aspect of Lata’s life is sexual violence which everybody including Lata is ignoring. She paints it as choice, even the incident when she was raped as a fifteen-year-old after which her psychotic episodes started. Her mother blames puberty and “heat” to be responsible for her mental state. Doctors even after concluding that she has histrionic personality disorder do not entertain the possibility of past trauma. Her bruises do not raise doubts that chosen relationships can also be violent. Her sexual agency drowns her victimization. Many cultural formulae dictate that in marriage and sex-work, there is no such thing as rape. Pinto in Conjugality Unbound, paints a critical picture of violence and autonomy making references to Mary Wollstonecraft’s calls for justice instead of agency to ensure remedy for violence.

Also read: Book Review: Freedom Fables By Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain

Women’s Sexual Victimhood

In her essay, Srimati Basu examines the links between rape, marriage, resource acquisition, shame and consent in the context of feminist theories and law. The recognition of rape as violence and not just property violation was a success. But the treatment of sex as a form of property embedded in systems of exchange and kinship, and the resulting inability of viewing rape as sexual violence alone is problematic. Women’s status is that of victims and economic dependents. Their sexual agency is recognisable only as a victimised and transactional sexuality.

Basu highlights the state’s protective realm that women are dragged into. This only results in the enhancement of communities’ and families’ control of their mobility and sexuality. Legality of sex is reliant on marriage rather than on consent or violation. Legal remedies only compensate for or restore this transactional order. Thus, marriage as a remedy to rape victims does not raise outrage in the patriarchal psyche of our society. Violence is restricted to some women instead of preventing it against all women.

Conjugality Unbound provides a necessary critique of marriage highlighting the control of women’s sexuality, mobility, productive and reproductive labour, and the questionable presence of their agency. The contributors analyse multiple facets and aspects of conjugality, thus questioning our understanding of conjugality as a stable category. While the essays displace marriage as a self-evident given, they ironically take patriarchy as a self-evident constant treating it as a bedrock of their critiques.

Women are either sanctioned sexual objects or victims, quandary is never between their sexual agency and victimhood. Rape legislation is undoubtedly problematic which raises a need for alternative justice mechanisms, but there is fear that a critique of this legal articulation might result in the withdrawal of the minimal and incomplete protection that it offers. Law and traditions do not view sexuality sans marriage, or marriage sans sexuality. Feminist theories need to take this as the core of the problem and proceed thereupon.

Takeaways

Conjugality Unbound provides a necessary critique of marriage highlighting the control of women’s sexuality, mobility, productive and reproductive labour, and the questionable presence of their agency. The contributors analyse multiple facets and aspects of conjugality, thus questioning our understanding of conjugality as a stable category. While the essays displace marriage as a self-evident given, they ironically take patriarchy as a self-evident constant treating it as a bedrock of their critiques.

Also read: Book Review: The Gurkha’s Daughter By Prajwal Parajuly

The volume as a whole gives a subtle critique of capitalism, although none of the authors explicitly mention it as a category but all examine how women are oppressed through the necessary labour demanded or expected from them, and how their economic state ensures their continued dependence and oppression. The book goes beyond examining marriage as a stage reached by persons (either necessitated by families and communities, or chosen by individuals). In doing so, it rectifies the lacuna in feminist and anthropological literature by discussing it as an experience lived by people and communities.

About the author(s)

Sumaiya Taqdees is a content editor, and a post-graduate in Political Studies from JNU. With a penchant for art, a love for ironies, and an aspiration to become a tree, she is a person of few words except when writing.