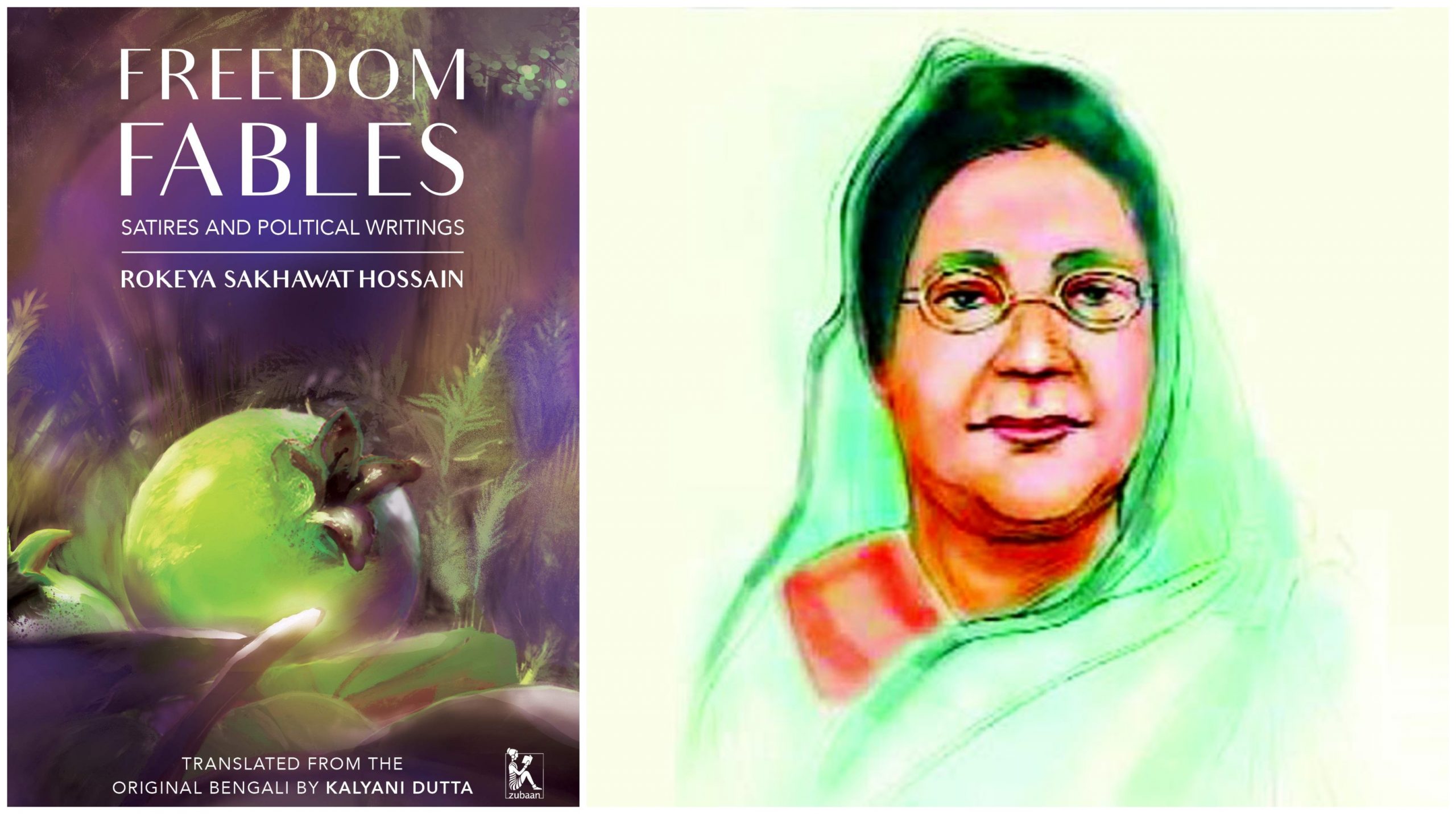

One of the fierce feminists of her times, Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain was a pioneering writer, too. In her lifetime, she advocated women rights through her writings. This slim volume called, Freedom Fables: Satires and Political Writings, published by Zubaan and exquisitely translated from Bengali to English by Kalyani Dutta covers her fabulist writings and a few poems, and closes with an unfinished work that’s left on her desk when she died a quiet death.

Through her fabulist and satirist approach, she critiqued society like no other from her time. Born in 1880 in Pairaband village in the Northern District of Rongpur in East Bengal, Rokeya, much celebrated for “Sultana Ke Sapne,” was a towering figure in education for girls of her times. She even started a school (in Bhagalpur) just after her husband’s death and moved to Calcutta with her mother, in 1910. But a year later, her mother passed away leaving Rokeya vulnerable. However, none of this deterred her from her aim of liberating girls and women through education.

Book: Freedom Fables: Satires and Political Writings

Author: Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain

Translated from the Original Bengali by Kalyani Dutta

Publisher: Zubaan Publishers Pvt. Ltd. 2019

Fight Against Patriarchy and Rokeya’s Writing Style

In “Amader Abanti” (Our Degradation) in Freedom Fables, she vehemently criticizes the male-centric world, the religious texts, and all the agencies that subjugated women. She writes,

“We have fallen as low as it is possible. Yet we have never raised our heads against this subjugation. The most important reason is that whenever a sister has tried to raise her head, the pretext of religion or commands from holy books have been used as weapons to smash her head. To keep us in darkness, men have declared religious texts as commands from God…So, you see, these religious texts are nothing but man-made rules and regulations.”

Because she wrote in the vernacular, and not in English, her readership was limited. Thus, she didn’t come into the limelight like other contemporaries of hers, for example, Pandita Ramabai. Her approach to ridicule society with wit and humor can be easily compared with Ismat Chughtai’s; however, the stark difference is in the imagery. Chughtai is far more realist and in-your-face feminist writer, but Rokeya was more of a fabulist-satirist.

Because she wrote in the vernacular, and not in English, her readership was limited. Thus, she didn’t come into the limelight like other contemporaries of hers, for example, Pandita Ramabai. Her approach to ridicule society with wit and humor can be easily compared with Ismat Chughtai’s; however, the stark difference is in the imagery. Chughtai is far more realist and in-your-face feminist writer, but Rokeya was more of a fabulist-satirist.

She elucidates the issues of desirability of a male child by women. She creates a world in Muktiphal, in which the mother – befittingly named Kangalini for she’s poor – is cursed because she desired boys, and not girls. And the curser even says to Kangalini, “Therefore, you will suffer at the hands of these beloved sons.”

A stark determined character seems to emerge, with the help of Shrimati, the ever confident matriarch who challenged her own brother by saying, “But brother, if you don’t let us raise our heads, you are not going to become strong either.” But men being men, even in this fable, were too ignorant and her brother responds that he’s not interested in her “lectures,” and commands her to do what she’s gendered to do by the society: wash some dishes.

The Problem With Sugrihini

No one, and my conviction grows stronger with every book that I read, for sure in her times was able to achieve in the field of written criticism of society which Rokeya did; however, there’s a problem that I figured while reading Sugrihini – the Ideal Housewife, in Freedom Fables.

The armchair philosophy in this story is something that I didn’t quite enjoy; it reeked of the idea of “purity” for me. The story ends with this, “We must remember that we are not merely Hindu, Muslim, Parsi or Christian, nor are we only Bengali, Madrasi, Marwari and Punjabi. We are Indians. We are first Indians – and only then Muslim, Sikh or anything else.” The moment we try to pit one of our identities – in this case, religious and regional – we’re saying that one part of our identity ranks higher than the other. We all perform intersectional identities. We’re many at one point of time, one at another, and none in an altogether different scenario. We exchange the positions of the oppressor and oppressed based on what particular position we occupy when and where.

Today, the intersectionality our feminist activisms need to be more pronounced than yesterday. I’m calling myself a feminist even though Manu Joseph seems to have a problem with being a feminist out of female body (again an “idea of purity”). We’re diverse, and everything that we do gives us an identity. Some people hate feminists, and that hatred gives us an identity too. If we’re to think of ourselves as “Indians” first, and then anything else, we’re missing the point; and the point is that no singular aspect defines us who we are.

The Great Divide: Haves and Have-Nots

Rokeya should be given the due credit that she’s one of the few who’re writing about peasants’ concerns, especially Bengali farmers – who despite their land being extremely productive of producing goods couldn’t quite do it, and were pushed to the margins.

She writes in Freedom Fables, “Our Bengal is well-watered, fertile, green with corps – but why is the peasant’s belly empty?” Interestingly, she critiqued the society here, too, which thinks that a writers’ and poets’ job is always to criticize. She writes, “No. This was not the fancy of a poet, not some literary text; this was our truth. All this existed in the past, and does not anymore. Arre! Now we are civilized. Is this progress? No use blaming civilization. The Great European War has impoverished the whole world; why speak of the Bengali peasant?”

Also read: Book Review: These Hills Called Home: Stories From A War Zone By Temsula Ao

Raising an important point that led to the great divide between the society and highlighting the stark division of “haves” and “have-nots,” she examines how all this happened. How people (Indians), in the Raj, exercised power and abused peasants. She explains,

“In Assam and Rongpur a kind of silk is found which is called ‘Endi’ in the local language. It is easy to keep Endi insects and make yarn out of their cocoons. This skill was a monopoly of the women of those areas. When they visited each other’s homes, they would carry the spindle and keep carding yarn while they strolled. Endi cloth is quite warm and lasts long. It is not inferior to flannel, yet it lasts longer than flannel. A piece of Endi cloth can easily last for up to forty years. If one has four to five pieces of Endi material, there won’t be need for quilt, blankets or kanthas made with old saris. And Assam silk was no longer available in Whiteway Laidlaw. Moreover, now Endi cocoons are sent to England and then reimported as silk yarn. The main point here is that as progress advanced, all native industries declined.”

She writes, “Our Bengal is well-watered, fertile, green with corps – but why is the peasant’s belly empty?” Interestingly, she critiqued the society here, too, which thinks that a writers’ and poets’ job is always to criticize. She writes, “No. This was not the fancy of a poet, not some literary text; this was our truth. All this existed in the past, and does not anymore. Arre! Now we are civilized. Is this progress? No use blaming civilization. The Great European War has impoverished the whole world; why speak of the Bengali peasant?”

The Beggar Queen and Narir Odhikar

With “Rani Bhikarini” in Freedom Fables, she jibes at the Hindu world, who’s displeased, along with Mahatama Gandhi, when an American writer, Mayo, exposed the caste divide in India and brought the Brahminical orthodoxy at the international level in her book: Mother India. She notes, “The Hindus may curse Miss Mayo to their heart’s content for stating the brutal truth, but the violence of their abuses will not transform a black crow into a white duck.”

Again, we’re dealing here with the idea of purity – when during the current oppressive regime’s times when there’s an ongoing protest (which has halted due to the novel coronavirus crisis) over the Citizenship Act, and when one says anything against the government, the person is asked to “Go to Pakistan,” we again see that no one has the right to criticize the government, which is now considered equivalent to criticizing the nation. She rebukes those puritanical forces, “However, the point is that what is good is already perfect and does not need to change. It is essential to reform that which is wrong.”

She further comments on the unbalanced power relationship between a man and a woman in marriage in Narir Odhikar saying, “In our religion, a marriage is completed only after the bride and groom have both consented. If, by mischance (let Khoda prevent it), it should come to divorce, it should happen by the consent of both. But why then, in practice, is divorce always one-sided, initiated only by the husband?”

Also read: Book Review: Women And Sabarimala By Sinu Joseph

To sum up, Freedom Fables is an enjoyable read, and one of the most important books to have been circulated in our times when women are at the forefront and leading protests all over India. By publishing such books, we’re crediting them their much-awaited due. And I think for that this must be in everyone’s bookshelves.