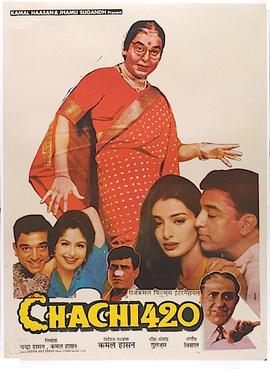

Aah 90’s/early 2000’s nostalgia! This was an era marked by iconic ensemble comedies (Andaz Apna Apna, Hera Pheri), frothy rom-coms and memorable original soundtracks (Dil Se, Saathiya). One of my favourite movies in the 90’s films category is Chachi 420 (1997), the Bollywood remake of Avvai Shanmughi (in itself inspired from Mrs. Doubtfire). Who can forget Bharti dancing while Chachi renders a pseudo-classical version of ‘Macarena’ in the midst of a Karva Chauth luncheon?

A recurring debate amongst cinephiles is whether movies of an earlier era should be enjoyed as they are or whether they ought to be given a relook in light of subsequent developments in culture and society. I personally believe it is important that we critically re-evaluate our judgements of older content if we are to keep re-watching them, celebrating them and imbibing the underlying symbolisms thereof. This is especially given that many of the regressive tropes used in ‘cult classics’ continue to influence contemporary film-makers, and the dearth of original scripts has given rise to a spate of ‘remakes’ (e.g. Judwaa 2) which reinforce these outdated tropes.

Another reason I find it relevant to take a re-look at Chachi 420 is because of the recent discourse surrounding portrayals of inter-caste romance in cinema. Contemporary inter-caste romance films (Sairaat, Pariyerum Perumal) are usually located in a rural or semi-urban setting, amidst a feudalistic family background. We rarely see how casteism affects love and gender dynamics in the context of urban capitalist spaces, which are stereotypically perceived as being more ‘cosmopolitan’ in nature. This is, even though series like Indian Matchmaking show that caste plays a role in ‘modern’ dating as well. In this regard, Chachi 420‘s portrayal of the misadventures of Jai and Janaki, an urban inter-caste couple, was quite ahead of this time.

To give a recap, the premise of Chachi 420 is as follows: Jaiprakash Paswan (Kamal Haasan), a lower-middle class assistant choreographer, falls in love with Janaki (Tabu), the only daughter of Durga Prasad Bhardwaj (Amrish Puri), a reputed Brahmin industrialist. After marital differences arise between the two (the final straw being a Thappad-style spat in front of their landlord and neighbours), Janaki divorces Jai and obtains sole custody of their daughter Bharti (baby Fatima Sana Sheikh). Jai masquerades as a Brahmin nanny, Laxmi Godbole alias ‘Chachi’, in order to be closer to his daughter. The resulting comedic mishaps form the rest of the plot.

If the movie had released today, there might have been calls to ‘cancel’ the scene where Jai spies on Janaki bathing, while he is in the guise of ‘Chachi’, whom Janaki treats as a mother figure. In another scene, Jai is slightly aroused when Janaki hugs ‘Chachi’. This kind of crass comedy depicting cross-dressing cis-het men fooling their wives, which is also present in films such as Golmaal Returns, may implicitly feed into TERF (Trans-Exclusionary Radical Feminist) stereotypes about how trans-women may misuse their femininity to sexually harass cis-women.

Over the years, Mrs. Doubtfire has drawn ire for featuring sexist and transphobic tropes. The same criticisms may be levelled at Chachi 420. Jai/Chachi constantly tries to emotionally manipulate his ex-wife Janaki by spouting outdated axioms such as ‘a husband and wife can separate but parents cannot separate’. Further, if the movie had released today, there might have been calls to ‘cancel’ the scene where Jai spies on Janaki bathing, while he is in the guise of ‘Chachi’, whom Janaki treats as a mother figure. In another scene, Jai is slightly aroused when Janaki hugs ‘Chachi’. This kind of crass comedy depicting cross-dressing cis-het men fooling their wives, which is also present in films such as Golmaal Returns, may implicitly feed into TERF (Trans-Exclusionary Radical Feminist) stereotypes about how trans-women may misuse their femininity to sexually harass cis-women.

Also read: 7 Anti-Caste Moments Of 2019 That Challenged Casteism In India

However, Chachi 420 is quite provocative if looked at from an anti-caste lens. The anti-caste critique is evident from the beginning of the narrative. When Durga Prasad is introduced to Jai, the first thing he does is to point out the portraits of successive generations of the Bhardwaj patriarchs. He then superciliously remarks, “After Durga Prasad Bhardwaj, the name Jaiprakash Paswan’ would sound out-of-tune wouldn’t it?” Some caste-blind critics may argue that Durga Prasad only had a problem with Jai’s class. If that was the case, Durga Prasad would have simply said, ‘After generations of rich businessmen, a poor dance master would be out-of-place.’ The emphasis on the surname smacks of casteism. The dialogue would not have been laced with so much snark if Jai’s surname had been ‘Kashyap’ or ‘Sharma’.

Unsurprisingly, it does not occur to Durga Prasad that Janaki could continue the family’s legacy. Caste and patriarchy are intertwined in India. An upper-caste woman who marries a lower-caste man challenges both patriarchal control and the maintenance of caste endogamy. Durga Prasad’s haughty disapproval of Jai masks his underlying fear that if Janaki marries a lower-caste man, the Bhardwaj name, and therefore his position in the caste hierarchy, will come to an end. He holds on to this belief even after Janaki divorces Jai. When Janaki quarrels with him over the presence of a Muslim cook (Nassar) in the house, he castigates her by saying, ‘This is not your house anymore. You have left your house behind. This is the house of Durga Prasad Bharadwaj’. The intersection of caste and patriarchy means that Janaki stopped being a ‘Bhardwaj’ for him the moment she married Jai, notwithstanding the subsequent change in her marital status.

Durga Prasad’s casteism is also apparent in his distaste when Chachi says her supposed ‘husband’ Hari (Johnny Walker), who is actually Jai’s makeup artist Joseph, is a ‘convert’. This has less to do with religious intolerance and more to do with the fact that Durga Prasad probably perceives Hari’s conversion as a transgression of caste boundaries.

Though Janaki summons the courage to elope, her own caste prejudice continues to make its presence felt. When Jai signs up Bharti for a film shoot without her consent, she angrily says, “The granddaughter of a Bhardwaj is not a (casteist slur) that she would work in the film industry!” Of course, as the child’s mother, Janaki had every right to object to the shoot, and Jai should not have subsequently slapped her. If she had chosen not to forgive Jai for his misbehavior in the climax of the film, it would have been justified.

I find it relevant to take a re-look at Chachi 420 is because of the recent discourse surrounding portrayals of inter-caste romance in cinema. Contemporary inter-caste romance films (Sairaat, Pariyerum Perumal) are usually located in a rural or semi-urban setting, amidst a feudalistic family background. We rarely see how casteism affects love and gender dynamics in the context of urban capitalist spaces, which are stereotypically perceived as being more ‘cosmopolitan’ in nature.

However, Janaki also represents the failings of savarna feminism. Though she is a well-educated working woman and a strong single mother, she is also someone who chides her lover for being a meat-eater. Durga Prasad is willing to forgive Jai’s friend Shiraz (Nassar) for masquerading as a Brahmin cook, but Janaki stands by her belief that they have committed ‘dharm bhrasht’ because of him. Janaki’s indignation does not really stem from religious sentiment or any intrinsic love for animals-after all; she works for her father’s company, which uses animal hides. What irks her is the violation of her caste taboos. Moreover, both Janaki and Durga Prasad stress that the candidates applying to be Bharati’s nanny must be Brahmin women, which is why Jai gives Chachi a ‘Chitpavan Brahmin’ surname.

Also read: Being An Anti-Caste Ally—5 Things To Keep In Mind

Therefore the characters of Durga Prasad and Janaki are testament to the fact that caste discrimination is not some outdated practice which is only present in ‘backward rural areas’ but thrives amongst the urban educated and so-called ‘liberal’ elite as well. Ironically, Jai has to assume the identity of an upper-caste woman for the two to see the error of their ways. It is ‘Chachi’ who points out that Durga Prasad’s vegetarian superiority complex is hypocritical because he is the owner of a company which fashions belts and shoes out of animal skin.

This brings to mind Dr. Ambedkar’s words, “Not only have the Brahmins given up their ancestral calling of priesthood for trading, but they have entered trades which are prohibited to them by the Shastras. Yet how many Brahmins who break Caste every day will preach against Caste and against the Shastras?” Real life Durga Prasads and Janakis should ponder over this, irrespective of whether a Chachi opens their eyes or not.

Reference

A Reply to the Mahatma by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar

Featured Image Source: ScoopWhoop

About the author(s)

Megha Mehta is a legal researcher based in Delhi.