Editor’s Note: Last month, that is July 2020, FII’s #MoodOfTheMonth was Feminism And Body Image, where we invited various articles about the diverse range of experiences which we often confront, with respect to our bodies in private or public spaces, or both.

Society has always been geared towards order – a stable structural condition has generally been extolled across space and time. Change, flux, flows have consequently been sources of much worry and anxiety, as they often herald the unknown. This basic tenet can be found working across many phenomena in society – be it the fear and distrust towards migrants or a revulsion towards change in general, human society has, time and again, reaffirmed its faith in statics and indicated its concomitant dislike of dynamics. An inherent reason for this pattern of preferences is the unpredictability of dynamics – that which cannot be predicted cannot be controlled, a major setback to a civilisational realm that obsesses itself with bringing everything under its control. It is in these domains that a crucial aspect of the gender order can be located.

Women have, for the longest time, been construed majorly in terms of their body and bodily states by mainstream society – a woman’s life stages are often demarcated in terms of attainment of puberty, (re)productive engagements and menopause. The image of the woman has thus, been tied to the body for long. On the other hand, women have also been likened to nature. This has had major implications for the ideas associated with womanhood. To be a woman, then, means to be a passive being, out there to be taken hold of, by some other agentic force.

Like nature, however, women are also unforeseeable and temperamental – almost akin to natural calamities, women’s emotions and moods cannot be managed effectively. This point has been repeatedly captured in cultural metaphors as well popular sayings in movies and other media – best embodied by the adage, “Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned.” Of course, the historical background of these ideas can be traced back to the notion of the hysterical woman, a major ploy to check women’s autonomy.

Like nature, however, women are also unforeseeable and temperamental – almost akin to natural calamities, women’s emotions and moods cannot be managed effectively. This point has been repeatedly captured in cultural metaphors as well popular sayings in movies and other media – best embodied by the adage, “Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned.” Of course, the historical background of these ideas can be traced back to the notion of the hysterical woman, a major ploy to check women’s autonomy.

These two strands of gendered symbolic order combined give us a situation where, interestingly, women are often associated with bodily fluids and substances. This, clearly, finds its strongest articulation in menstruation and the flow of blood that is so dreaded and tabooed. Constructions of women being majorly engaged with bodily fluids also portrays them as being preoccupied with their bodies and tied to nature.

But, what is most alarming is the added layers of meanings that are attached to this already gendered contriving – perceptions of dirt and danger populate these conceptions, so as to imply the conventional notions of women as dangerous and as likely to “get out of hand”. Intriguing, however, is the question: out of whose hand? An easy answer, of course, is men’s and larger society’s hands.

The phenomenon of women being in constant association with dangerous and dirty bodily fluids necessitates strict control over these. This control is initially the work of women – to ensure that their corporeal traces are diminished and erased, women have to be constantly on guard. Talk of menstruation as a taboo, and accommodations within public realms according to a woman’s menstrual cycles are unthinkable. Women must ensure that their bodily fluids are strictly hidden from the unflinching public gaze. Thus, a blood stain is acceptable as long as it is not due to menstruation.

Also read: Navigating Romantic Relationships In A Fat Body

This philosophical idea spills on to larger questions of space and spatial arrangement. Conventionally, work in the domestic sphere has been allocated to women and there is no end to the contentions that have been raised regarding the highly unequal situation that arises due to the unpaid, unrecognized forms of labour that women have to toil in under the roof of the house. Specifically, however, with respect to the question at hand, women have always had to bear the responsibility of ensuring that the house remains spick and span, tidied of all sources of dirt and disgust to its other members.

A sanitised space has to be produced within the house, more so with the onset of an age when domestic space is increasingly commodified and intruded by consumerist concerns – this is clearly exacerbated by the pandemic which requires a ‘presentable’ work-from-home station. What must be noted, nevertheless, is men’s role in this scenario. When things get out of hand, metaphorically, and when there are leakages in the sewage and drainage system, it is the men who take up the task of climbing up pipes and walls to repair the breaches – symbolically, this is equivalent to men arduously containing and restricting the damages wrought by women’s uncontrollability. Thus, men are the final upholders of the status quo of the society, who ensure its perpetuation by attempting to control women, both intimately and distantly, bringing violators to book.

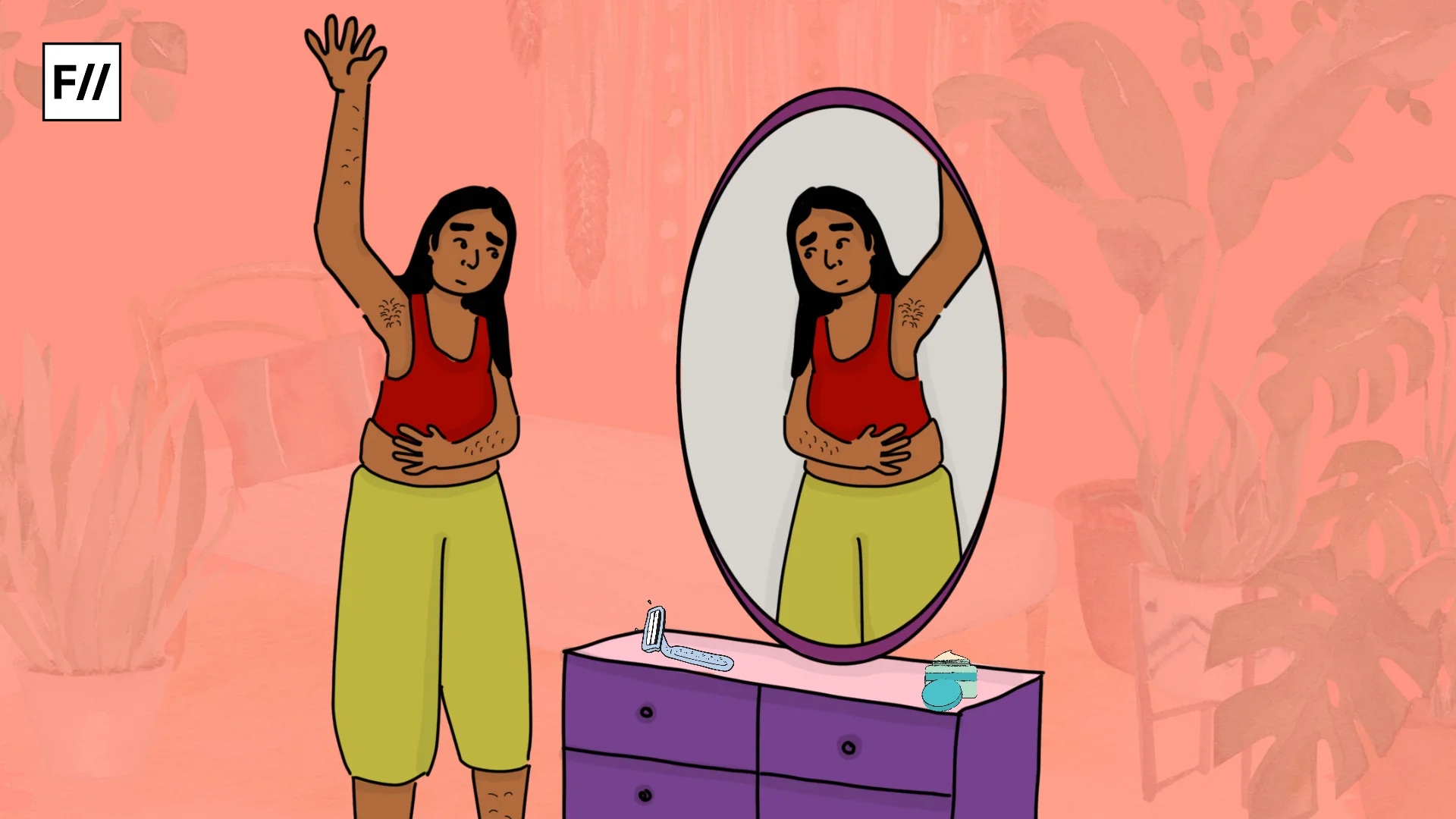

Self-surveillance is clearly the most dangerous form of monitoring – women are taught that their bodies must be managed – by themselves; if they fail at it, then, they will be met with violence. This goes on to, often, creating a situation, whereby, women themselves pay utmost attention to managing their bodies and ensuring that it is contained within definite boundaries – the body, thus, tends to assume the shape of a liability that women attempt to perform effectively.

Repeating falsehoods often give them the appearance of truths and socialisation has been one of the principal agents of inducing behaviour in women that corresponds to the above phenomenon. Self-surveillance is clearly the most dangerous form of monitoring – women are taught that their bodies must be managed – by themselves; if they fail at it, then, they will be met with violence. This goes on to, often, creating a situation, whereby, women themselves pay utmost attention to managing their bodies and ensuring that it is contained within definite boundaries – the body, thus, tends to assume the shape of a liability that women attempt to perform effectively.

While corporeal feminism has outlined the extreme discrimination and silent structural violence that women’s bodies have to face by virtue of such situations, the solution clearly lies in advocating an approach that goes along the lines of anarcha feminism – the way ahead lies in chaos, dynamic shifts and continuous innovations in strategies.

Also read: Why Do Mothers Body Shame Their Daughters?

Encouraging public discussions around menstruation is only a step in the longer path of allowing women to exert their bodily autonomy freely and reclaim space for themselves. One breach in the gender order is enough to produce ripple effects that can go a long way. Thus, strategic disruptions in the established hierarchies can pave the way for more effective and sustainable victories for women in the future.

Urbee Bhowmik is currently pursuing her Master’s in Development Studies at Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai. She has a Bachelor’s in Sociology from St. Xavier’s College (Autonomous), Kolkata. Urbee’s broad research interests include gender, migration, sociality and environmental sustainability among others and she has been associated with editorial work and academic writings. You can find her on LinkedIn.