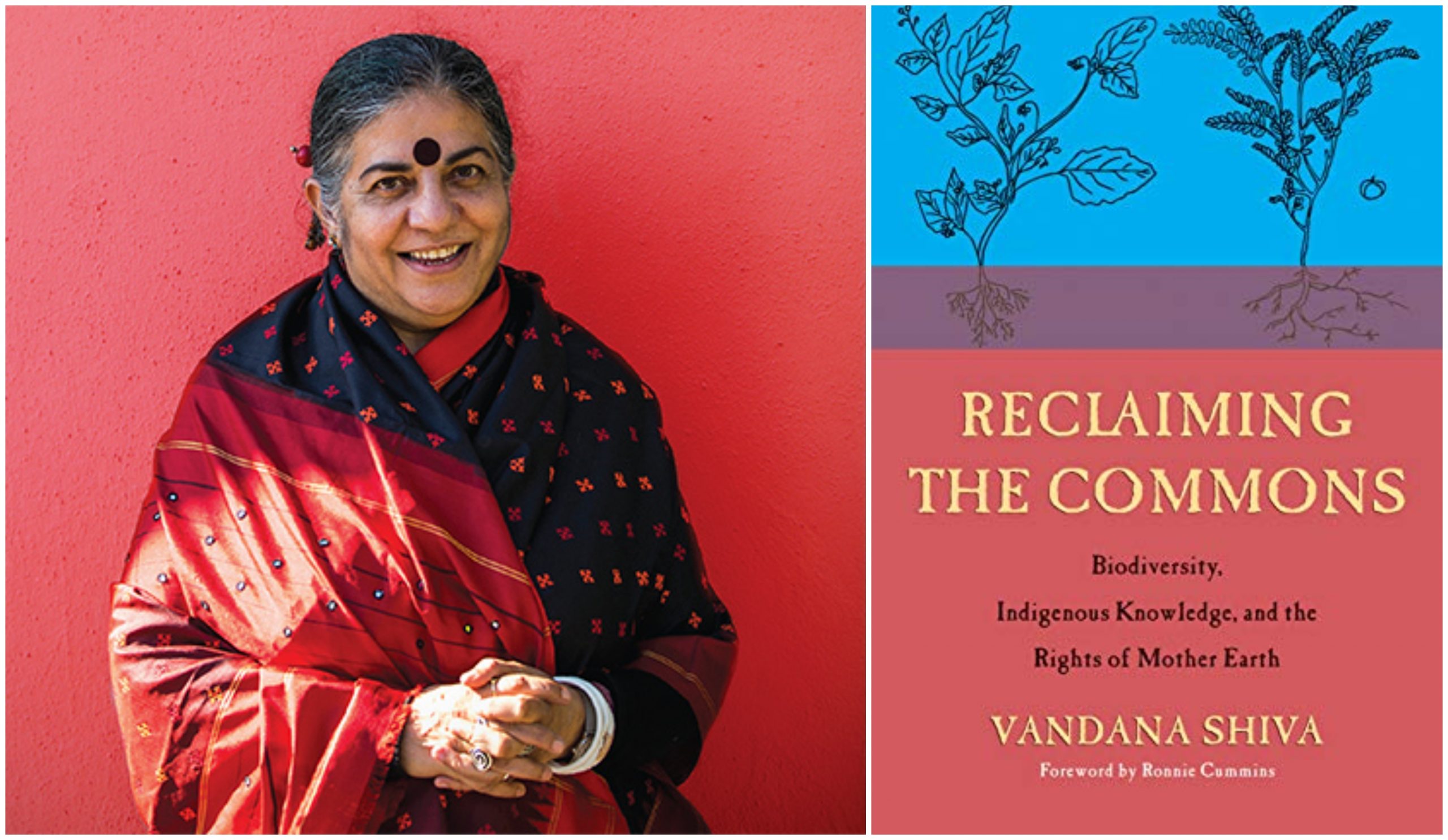

Vandana Shiva, the author of the book, “Reclaiming the Commons: Biodiversity, Indigenous Knowledge and the Rights of Mother Earth,” is an Indian scholar and an environmental activist, who has been at the forefront of the battle fighting corporate globalization that feeds on the efforts of farmers and indigenous knowledge systems. She is the founder of the Research Foundation for Science, Technology, and Natural Resource Policy (RFSTN), an organization devoted to developing sustainable methods of agriculture. She launched Navdanya (Nine Seeds in Hindi) in 1991 which has been significant in combating the practice of monoculture promoted by corporations and increase awareness regarding the benefits of biodiversity conservation and ills of the “Green Revolution.”

Reclaiming the Commons: Biodiversity, Indigenous Knowledge and the Rights of Mother Earth

Author: Vandana Shiva

Publication: Synergetic Press 1 Bluebird Count, Santa Fe & London (2020)

Genre: Non-Fiction

“Saving our planet, lifting people out of poverty, advancing economic growth… these are the one and the same fight. We must connect the dots between climate change, water scarcity, energy shortages, global health, food security and women’s empowerment. Solutions to one problem must be solutions for all.”

~Ban-Ki-Moon

The battle for and against biodiversity conservation has over time revealed a conflict of interests over those who has access to natural resources and those who in turn is benefited from its use. This book attempts to understand this ensuing conflict that has, for generations, defined and redefined the rights of communities in rural India on one hand, and the acceleration of global projects that have commercialized and marketed these ‘community resources’ for their vested interests, on the other. These two paradigms of conservation as the author suggests, is connected to different value systems for the different sections. While the traditional communities are dependent on these resources for survival, the global corporations are concerned with their use values that is only to the extent that they can maximize profits.

The battle for and against biodiversity conservation has over time revealed a conflict of interests over those who has access to natural resources and those who in turn is benefited from its use. This book attempts to understand this ensuing conflict that has, for generations, defined and redefined the rights of communities in rural India on one hand, and the acceleration of global projects that have commercialized and marketed these ‘community resources’ for their vested interests, on the other.

A significant idea that this book revolves around is the question of sovereignty of the nation and autonomy of the individual. The autonomy of the individual or the nation does not occur independently but is intertwined with the question of community rights. What the term ‘commons’ entail is in fact this interconnection.

Seed Sovereignty and Community Rights

‘It is an erasure and enclosure of the source of seeds; the culture of the seed and the commons of the seed.’

‘Commons’ are the resources that cannot be monopolized by a handful. The term itself suggests a strong attachment to community. Vandana Shiva states that, ‘…commons and communities are beyond the state and the market’. Community resources then mean that they are not just used collectively by a particular community but used in a way that ensures their sustenance for the future generations. This sustainability is ensured through a series of practices and knowledge, that are indigenous to these groups and are culturally significant for a given area and community—the control and exploitation of which not only leads to depletion of these resources but also puts the community and their traditional knowledge systems at risk.

An important relationship that the author explores is that between farmers’ rights and biodiversity conservation. What is central to this relationship is the ‘Bija’ meaning seed, which is again connected to life. Vandana Shiva beautifully uses ‘seed’ as a metaphor for a sovereign being. The seed is free and evolving. Its growth reflects that of the sovereign individual who is also self-organised and ever evolving without being intervened. However, as a result of western hegemonic ideas, this sovereignty is in a vulnerable position. Their idea of ‘improvement’ that rests on monoculture and the introduction of Genetically Modified Crops (GM crops) has created a monopoly of seed production thus creating an “enclosure of commons.”

Image Source: Navdanya

The Question of Agency and Farmers’ Suicide

‘The free sharing does not apply if there is commercial utilization of the variety of innovation. It should be assured that communities retain control over their resources, emphasizing the non-monopolistic facet of community innovation.’

An important step towards the protection of agricultural biodiversity has been The Convention on Biodiversity Conservation (CBD). Two important implications of this Act have been:

(a) To recognise the sovereign rights of the countries to their biological wealth, and,

(b) Recognition of contribution of indigenous communities to knowledge about utilization of biodiversity.

This recognition has created a major shift with regard to the question of ownership, use and control of resources particularly its production. The fact that GM crops have led to the replacement of farmers’ traditional agricultural practices with artificial breeding strategies has not only pushed farmers to poverty and malnourishment but also created a rift in their status as a producer as well as consumer.

For generations Indian farmers have been self-sustainable and relied on their traditional know-how to produce crops not only for their families but also for the Indian market. However, with the intervention of transnational corporations, there has been an increased pressure on the government to withdraw subsidy and provide greater incentives to the TNCs for investing in agricultural production in India. What this transition has created is an incongruence in the definition of ‘improvement’ for the farmers on the one hand, and global corporations, on the other.

The book explores how this intervention has created a shift in the food economy and knowledge system as well. The lack of autonomy of farmers over their inputs as well as outputs has pushed a lot of farmers in India to commit suicide. While ‘Green Revolution’ has been an important milestone in Indian Agricultural scenarios, but it has undergone a revolution in recent years that has only made agricultural communities more vulnerable and pushed them to adversity.

The author talks about this pertinent issue—‘Farmers’ Suicide’—which has been a fundamental area of concern. Suicide statistics are reliable for redressal and preventive mechanisms, but they fall short of pointing out the determinate causes of why suicide happens. The author states that rapid increase in indebtedness is at the root of farmers’ taking their lives. This indebtedness has been a result of trade liberalization and corporate globalization.

For generations Indian farmers have been self-sustainable and relied on their traditional know-how to produce crops not only for their families but also for the Indian market. However, with the intervention of transnational corporations, there has been an increased pressure on the government to withdraw subsidy and provide greater incentives to the TNCs for investing in agricultural production in India.

Yet the very constitution of Suicide as a category only remains limited to fit demographic aggregates. The very construction of the category of a farmer creates a lot of tension which in turn is influenced by an interplay of the state, the police and the rural citizen. Although the author touches upon agrarian crisis and farmers’ suicide, she doesn’t explore at length about how this agrarian crisis is aggravated by social and cultural factors.

Also read: In Conversation With Dr Vandana Shiva: Chipko Taught Me Humility

As the author states, the recognition of community rights would only be effective in so far as this recognition is not only limited to ownership of these resources but also their right to protect these resources through their traditional creative methods. These methods are largely rooted in a system of development, based on survival, harmony and cooperation. These ideals also reflect a significant element of how different communities have co-existed over years indulging in an array of exchanges that both benefit their communities and also replenish biodiversity.

Thus, a system of legal and political acts is the need of the hour to induce a more decentralised approach to these communities in terms of their rights and resources. It’s important to realise their agency and autonomy in doing so, and providing incentives to make them active agents in biodiversity conservation and not merely passive receivers.

She further draws a divide between the personal and political, and states how the West has merged the two in a state of perpetual adversity. Because the idea of ‘shared resources’ is non-existent in the western context, it has created a negative impact for Indian agricultural communities who for generations have relied on shared resources for survival.

Image Source: Navdanya

Criticisms and Conclusion

The author reflects extensively on how the struggle over the commons is interconnected with a larger struggle for ecological conservation and ownership rights. These rights are inalienable from the community, and as such entail a continuous struggle to deconstruct the meaning and idea of ‘progress’.

However, one aspect that the book lacks in is its discussion is the gendered aspect of the agrarian crisis. This becomes significant for the very archetype of a farmer, who is most imagined as a male although the impacts are more strongly felt for the women farmers. This is especially true in the context of farmers’ suicide wherein the woman is often left to tend to both the household chores as well as the field. Even under normal circumstances, a significant part of agricultural work is performed by the women farmers. Yet the woman’s position is only always limited to not more than a helper, thus depriving them of the agricultural output. Their ‘secondary’ position becomes more precarious for even though they continue to labor, they do not possess any ownership rights of their produce, even after the death of their husband.

Also read: Book Review: Staying Alive By Vandana Shiva

Furthermore, the book also fails to give an elaborate picture of the caste and class dynamic in relation to agriculture. Since most agricultural communities belong to upper caste-class, what would the question of “rights” entail for the peasant communities who have no land ownership?

Divisions in the farming community continue to prevail along caste and class lines in contemporary India where dominant communities (upper caste-class, politically powerful) continue to own land and landless labourers are forced to labour with no ownership. Social and economic mobility remain a distant dream for peasant communities (lower caste-class, Adivasis, Dalits) who have to take up non-farming occupation or migrate to urban centres for a living.

Nevertheless, this book is an important work towards the conservation of biodiversity and intellectual heritage while challenging separatist ideas of evolution and progress.

About the author(s)

A Sociology graduate with an interest in art and music. An enthusiastic reader especially concerning gender dynamics in mythological stories. A cat mom and an occasional photographer often found cafe hopping in Delhi.