From popular imagination to legal discourse, women’s bodies are characterized as victims of violence more often than perpetrators. There is good reason why this narrative exists; it informs protections of women and children in warfare, internalizes understandings of gender power dynamics, and to some extent, enables survivor-centric sexual assault policies. It is however, not entirely intersectional as it obscures the agency of women engaging in violence.

In revisiting mid-twentieth century Telangana, a poignant challenge to this narrative comes out in the militant women of the Telangana People’s Struggle. By pushing against what has been termed as a “formula for erasure and banalisation,” understanding women’s agencies in militancy and violence is central to amplifying the voices of caste and class oppressed peoples.

The Telangana Peoples’ Struggle (also known as the Telangana Peasants’ Struggle or the Telangana Armed Struggle) was an anti-feudal and anti-caste movement against the Nizam of Hyderabad’s oppressive regime, and later that of Independent India. In many ways, it was inherently feminist—with numerous women leaders advocating for socio-political reform not limited to caste justice, labour protection and women’s freedom. The armed movement lasted from 1946-1951 and was one of the first major labour uprisings following India’s Independence in 1947.

Historical Background

In the princely state of Hyderabad, people belonged to three broad linguistic identities—Telugu, Kannada and Marathi. The Telugu-speaking Telangana region constituted over fifty per cent of the state (including the capital, Hyderabad). With the Nizam, Mir Sir Osman Ali, and Muslim elites at the top of the state’s exploitative hierarchy, caste-Hindu zamindars (landlords) and money-lenders physically and sexually exploited agricultural labourers, perpetuated vetti (bondage), charged exorbitant interest on cash and grain loans, and forcibly evicted small-landowners. Lower-caste and Dalit-Bahujan women formed a large section of the six-million strong agricultural labour force and were slated to not benefit from India’s Independence.

Since 1938, the Hyderabad state witnessed marked growth in dissent, particularly among students and youth, against the Nizam as well as British colonialism. The Communist Party of India (CPI) was significantly involved in propagating a specific type of anti-imperial nationalism which overthrew tyrannical social institutions perpetuating labour abuse.

To aid the decolonisation and revolutionary process, local functionaries of the CPI such as the Andhra MahaSabha (AMS) were established to enable village mobilization through Sanghams (local committees) against the zamindars and Razakars (Paramilitary militia of the Nizam). By the 1940s, Sanghams proliferated much of present-day Andhra Pradesh and Telangana and became centers of village political organization against the landlords. Often, village ‘republics’ taken over by Sanghams would redistribute land to the peasantry, much to the chagrin of the wealthy land-owners and Razakars.

The Telangana Peoples’ Struggle (also known as the Telangana Peasants’ Struggle or the Telangana Armed Struggle) was an anti-feudal and anti-caste movement against the Nizam of Hyderabad’s oppressive regime, and later that of Independent India. In many ways, it was inherently feminist—with numerous women leaders advocating for socio-political reform not limited to caste justice, labour protection and women’s freedom.

Women in Arms

One of the most popular leaders of the movement was Chityala Ailamma (Chakali Ilamma), who asserted the rights of the lower-caste labouring classes, and specifically women, to cultivate their own land and reject caste-Hindu supremacy. As a Bahujan labourer, her militant defiance to the Razakars inspired hundreds of women to join the armed struggle. Ailamma’s pioneering dissent became a rallying call for peasant women to defy gendered domestic expectations, as well as structural oppression at the hands of the land-owning caste-Hindus.

Notably, women’s revolutionary activity in the Telangana struggle was in contrast to their upper-class and caste-Hindu counterparts in the 1920s armed revolution against the British. Peasant women in 1940s Telangana militancy were overwhelmingly disenfranchised by caste, class and educational and political opportunity. However, they played greater roles in planning and mobilization, while leading Sanghams, which doubled as village defence squads, in armed raids.

Also read: Belli Lalitha: The Nightingale Of The Telangana Resistance

Ironically, women of the Telangana movement seldom get their due credit while the likes of Suniti Chaudhary, Bina Das, Durga Devi and Pritilata Waddedar have comparatively lasted longer in public memory. Women of the Telangana movement are conversely memorialized as a mass, and not individual actors.

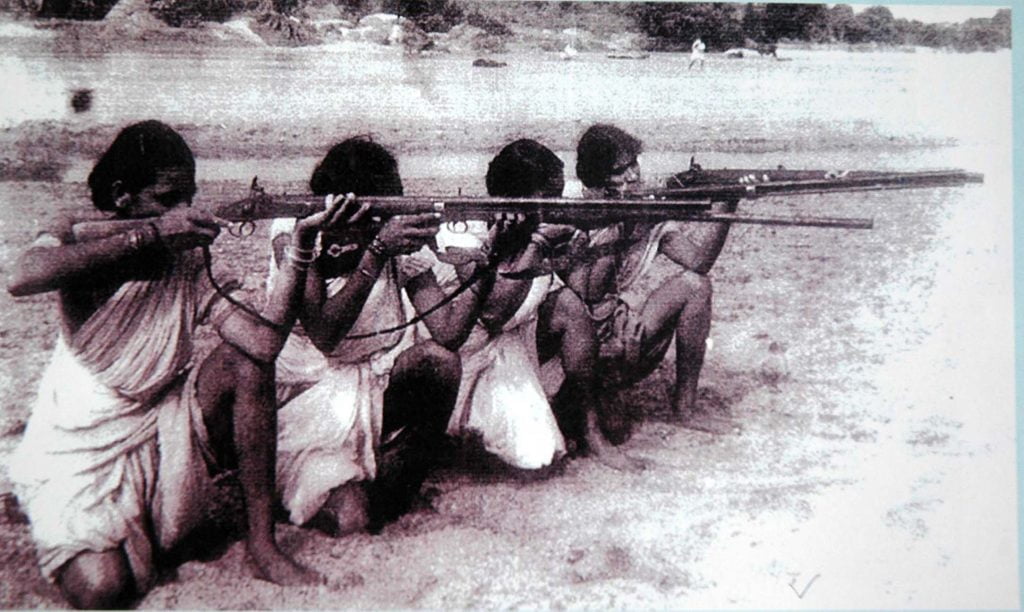

In 1989, the Stree Shakti Sanghatan published a collection of oral histories, We were making History… of dozens of female combatants, exposing powerful expressions of empowerment. Truly, the gun-toting female cadres of the movement also represented a uniquely violent female reclamation of political space. As a result of the movement, many women were venturing outside their homes alone during the nighttime for the first time in their lives, training with village defence squads, and traversing forests and formerly unfamiliar geographies.

Image source: The New International.

Moreover, women appropriated domestic objects like brooms, pestles, knives, slings and chilli powder as battle weapons with remarkable success. While the CPI and AMS provided rifle training to female fighters, women individualized their experience as violent combatants with new weapons.

A feminist reading of the struggle emphasizes the particularities and not just the roles or contributions of Dalit-Bahujan, and lower-caste women. By bringing the home and domestic into the conflict, whether through ingenious weapons or resistance against masculinist oppression, women of the Telangana struggle expanded the platforms of what female dissent looked like and what it meant to be a violent revolutionary woman.

The ancillary outcomes of the CPI’s and AMS’s mobilization of women included political and literary awareness since Sangham meetings featured talks and updates about imperial conflict (especially during World War II) and political developments in Northern India. While it is true that the CPI carved ideological and physical space for women to carry out violence, women designed revolutionary activity through their agencies.

Also Read: Bimala Maji And Intersections Of Class, Caste And Gender In Tebhaga Movement

Conclusion

Following the bloody annexation of Hyderabad by the newly independent Indian state in 1948, the Nehru government launched an offensive against the rebelling peasants. The intervention of the Indian army saw over 3 lakh people tortured and nearly 50,000 arrested and kept in detention camps (5,000 of which were imprisoned for years on end). The Indian armed forces brutally crushed the movement by October 1951. However, there were fleeting successes of the rebellion, including the abolition of vetti and land redistribution among the lower-castes.

Indeed, the movement expanded the spaces and platforms where and how women engaged in politics, but more importantly it expanded notions of who could engage in politics, that too violently.

A feminist reading of the struggle emphasizes the particularities and not just the roles or contributions of Dalit-Bahujan, and lower-caste women. By bringing the home and domestic into the conflict, whether through ingenious weapons or resistance against masculinist oppression, women of the Telangana struggle expanded the platforms of what female dissent looked like and what it meant to be a violent revolutionary woman.

References

- Vasantha Kannabiran, and K. Lalita’s “That Magic Time: Women in the Telangana People’s Struggle.”

- Kannabiran, Vasantha and Lalita, K’s We Were Making History: Life Stories of Women In the Telangana People’s Struggle.

- D N Dhanagare’s Peasant Movements in India 1920-1950.

About the author(s)

Sajneet is a History nerd who loves to bicycle.