Whether we like it or not, mass media plays an important role in shaping discourse related to health. Demonstrably, inaccurate or inaccessible renderings of medical research, dangerous narrativisation of healthcare workers and often, and propaganda-esque proclamations on medicine, mar Indian health reporting. Solving for these impediments to journalistic nuance is a steeper hill, as public health so often becomes political in India. It is worthwhile reflecting on the gross inequity the situation reveals—misinformation and disinformation on such an intimate subject.

This piece analyzes a few recurring themes in health and medical journalism in India, whilst flagging caveats related to the issues that journalists face in creating credible and investigative reportage.

Translating Research

For the majority of the population, scientific jargon is inaccessible, even for individuals who have completed post-secondary education. Further, it is increasingly difficult to translate bio-medical parlance for the masses, due to terminology-laden research reports and press releases. In India, translations into local languages are necessary to extend the reach of verified bio-medical information. This purpose especially seeks to counter unscientific health-related rumours that often vilify marginalised groups—women, persons with disabilities and/or mental illnesses, queer individuals, religious minorities, lower-caste workers, racialised communities among others.

Unsurprisingly, this goal seldom materializes in media. Due to the lack of time, space and knowledge, many journalists publish low quality health reportage. With harder-to-read research, journalists scramble to communicate the gist, if someone else (a doctor, government programme) has not already done it for them. Moreover, health news, if ever substantiated, often cites questionable studies. In these hasty attempts to overcome bio-medicine’s inaccessibility (or to generate panic or click-bait), reporters often resort to oversimplifying research findings. Examples of this oversimplification include conflating correlations with causation, inattention towards the stated limitations or biases of studies, and cherry-picking research to suit a favourable narrative.

Senior Journalist KG Suresh rightly notes that, “[p]ublic health reporting based on unverified, unsubstantiated and unattributed information can have disastrous consequences on the public at large.”

How individuals navigate their own and public health depends on the information they receive. Public Health is at risk due to the poor quality health reportage. And since the existential stakes of health-related and medical knowledge are very high, health reporting must do better.

Bio-Medical Data: Reliable Enough?

Moreover, scientists are as blameworthy as journalists communicating health information.

Bio-medical research is notorious for its biased datasets. For long, it has discriminated against marginalised people’s bodies by labeling them as non-normative, and imposing treatment for diseases that manifest differently on their bodies. Women, for instance, present symptoms, unlike men’s for the same conditions. They are hence discouraged to access treatment since as they have been historically underrepresented in clinical trials. In India, this looks like women accessing hospitals at dramatically lower rates than men, outside reasons like prevalence of disease.

Also read: Covid-19: Why are Women more vulnerable to Mental Health Issues?

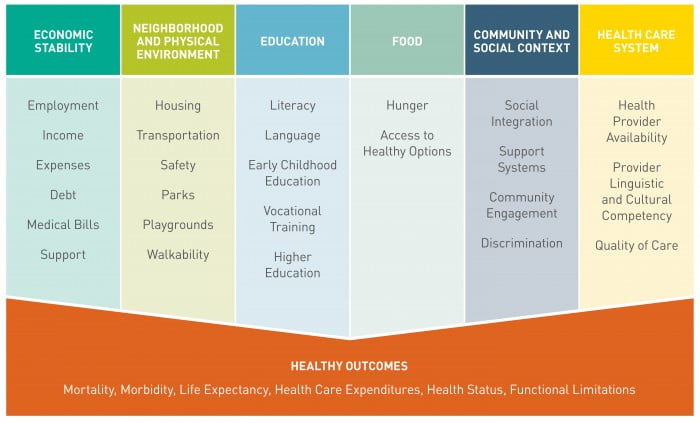

Sample composition is one of the biggest causes of bias i.e., how diverse are the study’s participants. Participant diversity is key for a robust and generalisable outcome. It’s a simple concept—result applicability, validity and scope increases with the variety of variables accounted for in a study. Such variables can include distance to the nearest hospital, incidence of caste discrimination, linguistic barriers to medical information, diet, religion, exposure to air pollution etc. Predictably, clinical studies disregard these variables (also known as social determinants of health) as they are difficult to measure and verify, and recruiting based on those determinants is a Herculean task.

In India, a physician typically reaches out to their existing patient pool for clinical trial recruitment. Many researchers also register their study on the Indian Council for Medical Research (ICMR) online Clinical Trials Registry (CTR) which opens up recruitment for a wider audience. Alas, we cannot discount its inaccessibility; accessing a digital registry requires English comprehension skills, internet literacy and most importantly interest in the absence of incentive.

In news media, studies performed on primarily white (even if gender-balanced) samples are often generalized to Indian populations (think about the eye-catching headlines of how eating pineapples is linked to higher intelligence); but, even studies conducted in South Asia do not entirely account for social determinants of health that influence an individual’s underlying health conditions and access to healthcare. Since participant diversity is difficult to achieve, research does not always apply to large populations.

The blame of low quality mass reporting, hence, falls onto both researchers, and reporters without medical degrees (myself included). With persistent problems in bio-medical data construction, ungeneralisable results are communicated without nuance. The ramifications of such misinformation are grave, as medical information tends to be revered by the public.

A Divine Incarnation, “Male nurses” and Ward “boys”

One of the primary ways in which media shapes discourse is by creating accessible vocabularies. In the process, media trivialises mental health, gendered effects of healthcare and medical labour.

One such example is “male nurses.” Besides the gender-binary imposed by the word “male”, an even closer examination reveals the gendered aspects of the medical and care industry. Attaching the gender descriptor implies that it is an exception to a norm i.e. without the addition of “male” you would envision nurses as women.

It is true that women are overwhelmingly represented in the care industry due to connotations of “feminine work” that draws from “female” protective instincts. However, it is sexist to assume women best perform as health care workers as nurses only. Women doctors often report patients mistaking them as nurses despite visible indicators such as ID cards and name tags. Similarly men have reported being mistook as doctors when they are in fact nurses.

“Ward boys” is another. It appears benign, but is nonetheless problematic. It mitigates the dignity of the work they perform as if it is child-like. In fact, nurses, physicians’ attendants and ward workers perform necessary medical labour; but they often receive less respect than is warranted. “Ward boys” infantalises adults who are essential workers in the health care industry.

Also read: Infographic: How to Sensitively Report Suicide

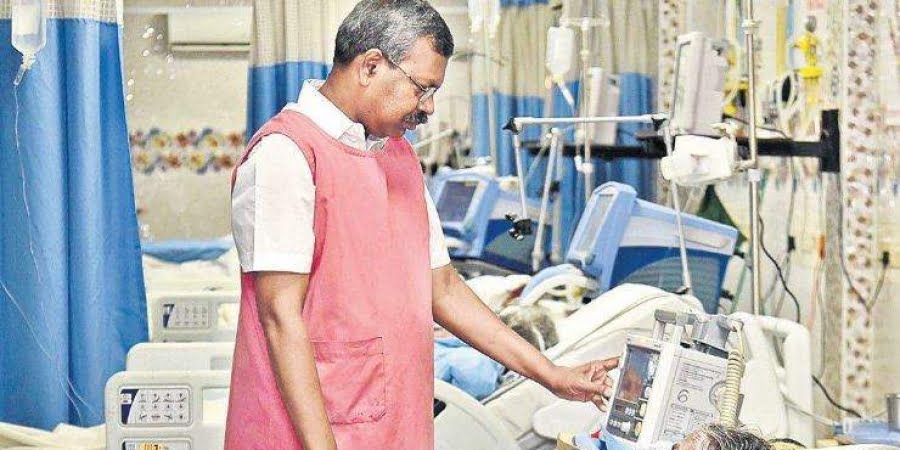

Perhaps the least obvious yet most threatening is the narrative of doctors as ‘gods’. The trope supposes that doctors are a divine incarnation who perform miracles and on whom prayers work. As saintly figures within this framework, doctors are expected to accept the status quo because they supposedly benefit from the reverence of being ‘godlike’. It internalises an expectation—that doctors must save lives and anything else is an indignant dereliction of duty. Hence, healthcare workers (doctors included) who challenge or fail to live up to this internalised idea are threatened and assaulted.

The Indian Medical Association reports that nearly 75% of doctors in India face violence in the workplace. Early-career or young and womxn doctors are more likely to face physical and verbal violence.

In the context of COVID-19, this narrative is “strategic messaging” to convince people that healthcare workers are necessary collateral damage in a fight against disease. It glorifies healthcare workers (albeit not all of them) as heroes in the face of adversity, distracting the public from issues faced by doctors due to government apathy. Amidst India’s COVID-19 response, government doctors in five states are working unpaid. Understandably, the over-enthusiastic liberal masses clapping and clanging utensils are deaf to these concerns as long as doctors are “doing their jobs.”

A critique of the god-narrative is in no way an ungrateful lament directed towards healthcare workers’ labour. It actually recognizes that doctors face scrutiny from patients and institutions for not fashioning themselves to fit the ‘god’ role. What does this scrutiny look like, you may ask? It looks like mob violence against healthcare workers who are unsuccessful in treating terminal conditions (for reasons apart from negligence). It includes police violence meted out on dissenting doctors and disciplinary action against those demanding Personal Protective Equipment (PPE).

Health as Propaganda

Coupled with lack of medical or statistical knowledge, malevolent propaganda worsens the quality of health reporting. Shortly after WHO declared COVID-19 as a pandemic and India went into state-sanctioned lockdown, Indian media launched a blame-game tirade. Notably, coverage of the contagion following the Tablighi Jamaat convention in New Delhi blamed Muslims for spread the coronavirus in India. Private news channels referred to those affected as carriers of the “Tablighi virus”, “human bombs” and “Corona bombs“, “traitors of the nation” or performing “Corona Jihad.”

Such hateful and insensitive characterisations are epitomes of bad journalistic practice around health care. Granted, it is reductive to claim that nuanced health reporting is easy in India. Investigative reporting by Indian and Kashmiri journalists on the institutional failures comes at the cost of reprimand, detainment or arrest and physical assault. In the early days of the lock-down, the Prime Minister instructed print media journalists and “stake-holders” to publish “inspiring and positive stories.” Over fifty reporters have been arrested during the lockdown for their criticism of the Centre’s COVID-19 response.

The acceptable voices are unfortunately those which appropriate public health to vilify minority groups, and conveniently sideline the same to celebrate a temple borne out of hate. The asymmetry highlights news’ media’s divisive tendencies, vocalizing the ruling party’s Islamophobia, jingioism and violent masculinity. Disinformation of this sort gravely endangers public health, both physically and in terms of civic life.

Health and Medical Journalism: A “Report” Card

Admittedly, news media is not the sole source of medical and health information. ASHA (Accredited Social Health Activists) workers and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) distribute valuable health communication in India. Additionally, in both rural and urban communities, religious bodies and traditional healing focused on astrology, ayurveda and folk medicine.

But, in the era of WhatsApp and high political literacy, news media is a prominent (and arguably, loud) voice of health communication. Indeed, observations of only English and Hindi mainstream news media limit this article; However, these issues are not unique to specific kinds of broadcast journalism.

How individuals navigate their own and public health depends on the information they receive. Public Health is at risk due to the poor quality health reportage. And since the existential stakes of health-related and medical knowledge are very high, health reporting must do better.

Featured Image Source: The Print

About the author(s)

Sajneet is a History nerd who loves to bicycle.