Posted by Manmeet Kaur

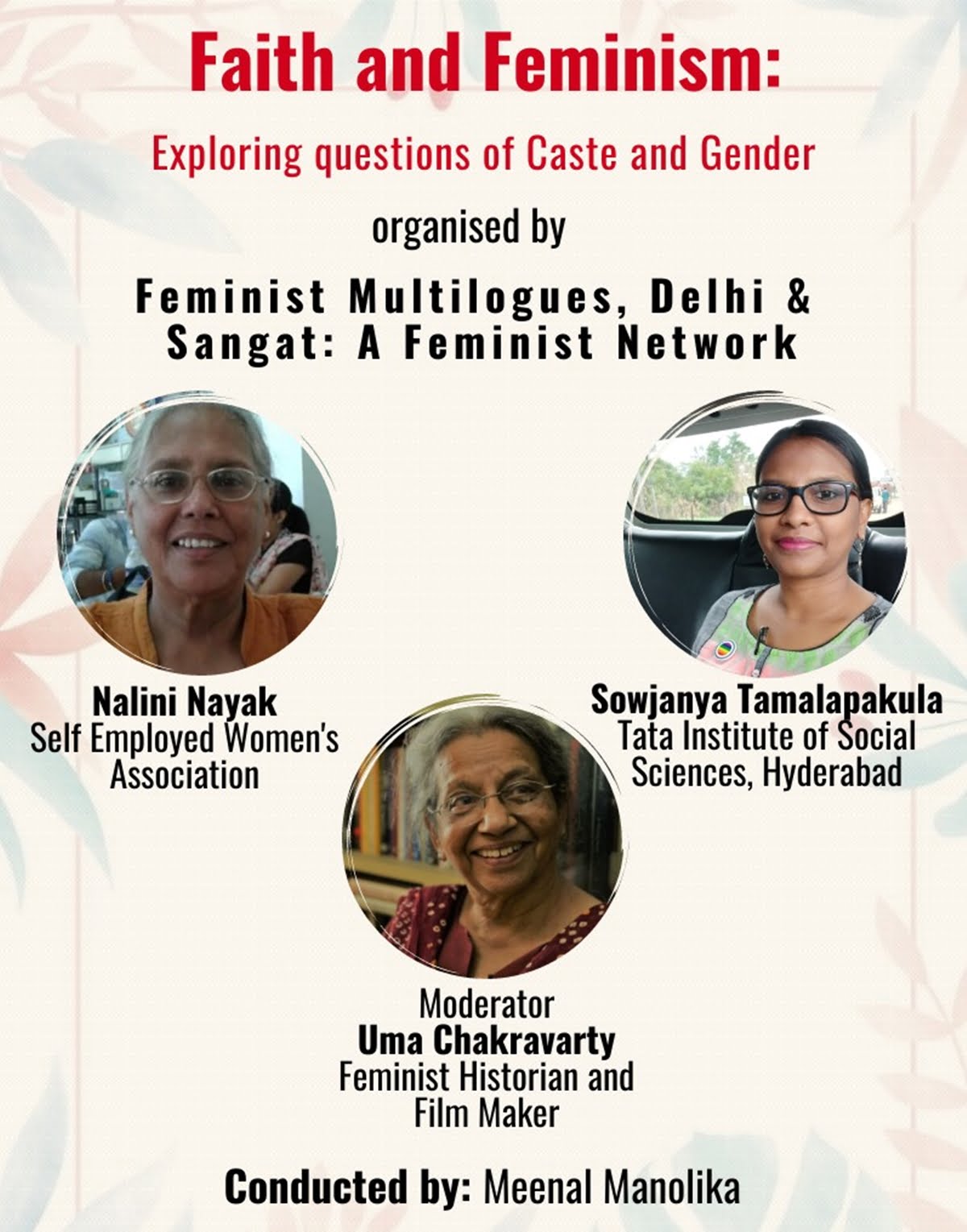

We’re at a crossroads. Of course as a society, but as individuals too. There are multiple threads which make up the complicated design that we put forth, and like all good labour, the tapestry hides the effort. One such uncovering was held on 25 July 2020. Faith and Feminism: Exploring Questions of Caste and Gender was the second in a series of talks on religion and feminism organised by Feminist Multilogues, Delhi and Sangat. Perspectives from Christianity and Navayana Buddhism from an intersectional feminist lens were shared by Nalini Nayak and Sowjanya Tamalapakula. The discussion was moderated by Dr. Uma Chakravarty.

Perspectives from the religion of Christianity and Navayana Buddhism from an intersectional feminist lens were shared by Nalini Nayak and Sowjanya Tamalapakula. The discussion was moderated by Dr. Uma Chakravarty.

Also read: Women Qazis- A Step Away From Patriarchal Religion

Dr. Uma Chakravarty began the discussion with a short recap of Faith and Feminism, Session 1, and its focus on understanding the first generation Indian feminists’ engagement with institutional religion, and building a feminist consciousness within patriarchal structures of faith. What followed was a beautiful narrative description of Urmila Pawar’s writings on her family’s renunciation of Hinduism, symbolic in the floating away of Hindu deities in the river, and their subsequent conversion to Buddhism. Pawar is a leading Marathi Dalit writer, and the family’s conversion like many others’ came as a ripple effect of Babasaheb Ambedkar’s conversion and rejection of the Hindu caste system. This narrative paved the way for Nalini and Sowjanya to pick up on the overlapping questions of caste, gender, and religion – discussing the tussle/cordial relationship amongst these identities through their personal journeys and political engagements.

Nalini Nayak dwelled on the intersections of a religious, political, and feminist identity, building it by layers in her exquisite storytelling of her personal journey. She discussed the changes in institutional Christianity religion which came with the Vatican Council, and the evolution of the Theology of Liberation in the Brazilian context in the latter half of the twentieth century. The simultaneous development of the Pedagogy of the Oppressed by Paulo Freire lent a rigour to critical interpretations of the Bible, the energy rubbed off and how! Multiple tracts of the movement took shape in South India giving way to two critical approaches- the methodology of education as reflection, and the participation of people in their own well being. Her personal journey of first encountering Marxism, and then Feminism found meaning in the application of these concepts to her work with the fishing communities. This brought home a ‘materialist reading of the Bible’ and ‘Marxist social analysis’; and cross cutting it all, was of course, a feminist lens. What awed her, was how the meaning of texts can transform completely by its interpretation and by extension, the interpreter. The understanding of casteism layered it all, lending a new understanding of the bodily smells of the fishing business, and the political organisation of the communities around that.

Sowjanya Tamalapakula took the threads forward with her discussion of the understanding of caste in the religion of Hinduism, and the possibilities of equitable realisation which Navayana Buddhism offers.

Sowjanya Tamalapakula took the threads forward with her discussion of the understanding of caste in the religion of Hinduism, and the possibilities of equitable realisation which Navayana Buddhism offers. She started her narrative by giving the example of the Jogini system organised on the basis of caste, which lies at the other end of the Devadasi system, leaving the Jogini devoid of a livelihood. She also explained the applicability of Brahmanical norms of sexuality, purity, and morality, on Dalit women, who fall prey to upper caste patriarchal violence. Interesting also was her description of the pervasiveness of Brahmanical marriage sanctity on all castes’ marriages. She underscored the relationship between gender and caste by discussing the possibilities of dismantling endogamy through queer engagements. Further, she discussed the nature of Buddhism itself. Sowjanya described Buddhism as the religion of ideals and the soul, instead of ritual and sacrifice. Dhamma being open to all, and good and bad acts being a internal function in Buddhism, Sowjanya discussed how this could offer a way of thinking of patriarchal, sexual blame differently. She also illustrated this with the stories of Amrapali, Angulimala, and Prakriti.

The discussion was tied in beautifully by Dr. Chakravarty, and the audience questions. Dr Chakravarty brought in pertinent questions regarding a woman’s religious choices, and the extent to which a complete renunciation of a religion is even possible, given the beliefs religious patriarchy functions with.

Dr Uma Chakravarty brought in pertinent questions regarding a woman’s religious choices, and the extent to which a complete renunciation of a religion is even possible, given the beliefs religious patriarchy functions with.

While the speakers agreed and advocated personal spiritual paths, there was a deep understanding of the multiple structures which may and indeed, do hinder this fluidity. In fact, aside from differences in religious belief systems, communities created by religious affiliation may be desirable as a support system for women. Dr. Chakravarty also questioned the distance there is to travel between the ideals of equitable religious beliefs, and their manifestation in everyday lives governed by existing structures of inequity.

In this section, Sowjanya shared that the Bible contains contradictory views on women as it was a compilation of several writings, she condemned the claims of absence of patriarchy in Dalits by the male-centric Dalit movement, and also discussed the perpetration of rituals and institutions in Buddhism. Introducing Ramabai into the discussion, Dr Chakravarty also brought in the movement of a feminist consciousness from one religion to another, talking about the fight against inequality as a struggle against institutional authority rather than a particular religious belief.

Also read: On Feminism, Religion And Right To Worship

Some of the interesting themes that came of the Q&A session were: the politics and possibilities of religious conversion for a woman, the translation of a feminist consciousness to a religious one within and across religions, and the difference between the institution of religion, and the community it offers. A thought that Nalini Nayak left us all with is worth a mention: “How are these overlapping ideas communicated to the next generation? How does feminist practice of religion in a stratified context pass from one generation to the next?”

These discussions do not by any means offer all the answers, but they do take a step forward in unfolding multiple tapestries, and finding similar threads across persons, communities, and identities.

Manmeet Kaur leads Gender and Equity programmes for an Indian education non profit. She is an English literature graduate from Lady Shri Ram College for Women, Delhi University, and has a Masters in Gender and Development from Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex, UK. She loves to combine feminist thought and concepts with storytelling and creative expression, and is an active member of the Delhi One Billion Rising team, a global movement against gender based violence. She can be found on LinkedIn.

About the author(s)

Sangat is a network of organisations and individuals working towards building and strengthening regional feminist solidarity through capacity building, campaigning and promotion of feminist culture.

Bhagwan Mahaveer Viklang Sahayata Samiti (BMVSS) is the world’s largest organisation rehabilitating over 1.78 million amputees and polio patients by fitting/providing artificial limbs (Jaipur Foot variety), calipers, and other aids and appliances, mostly in India and also in 27 countries across the world. For more visit: http://jaipurfoot.org