Trigger Warning: Mentions of self-harm, suicide, rape and assault

Safia (50) and Gudia (28) set themselves on fire on July 17 in the evening some time this year, in the middle of Lucknow’s high-security zone, on a road that houses the Lok Bhawan and the Chief Minister’s office. While Gudia is stable, Safia succumbed to 90 percent burns after being rushed to the hospital. In fact, the last couple of weeks of July witnessed multiple cases of attempted suicides through self-immolation. The majority of cases were painted political and forgotten amidst the humdrum of ‘more relevant’ news, but the act of self-immolation of a mother and a daughter unmasked a debate on the ritual of women burning in India.

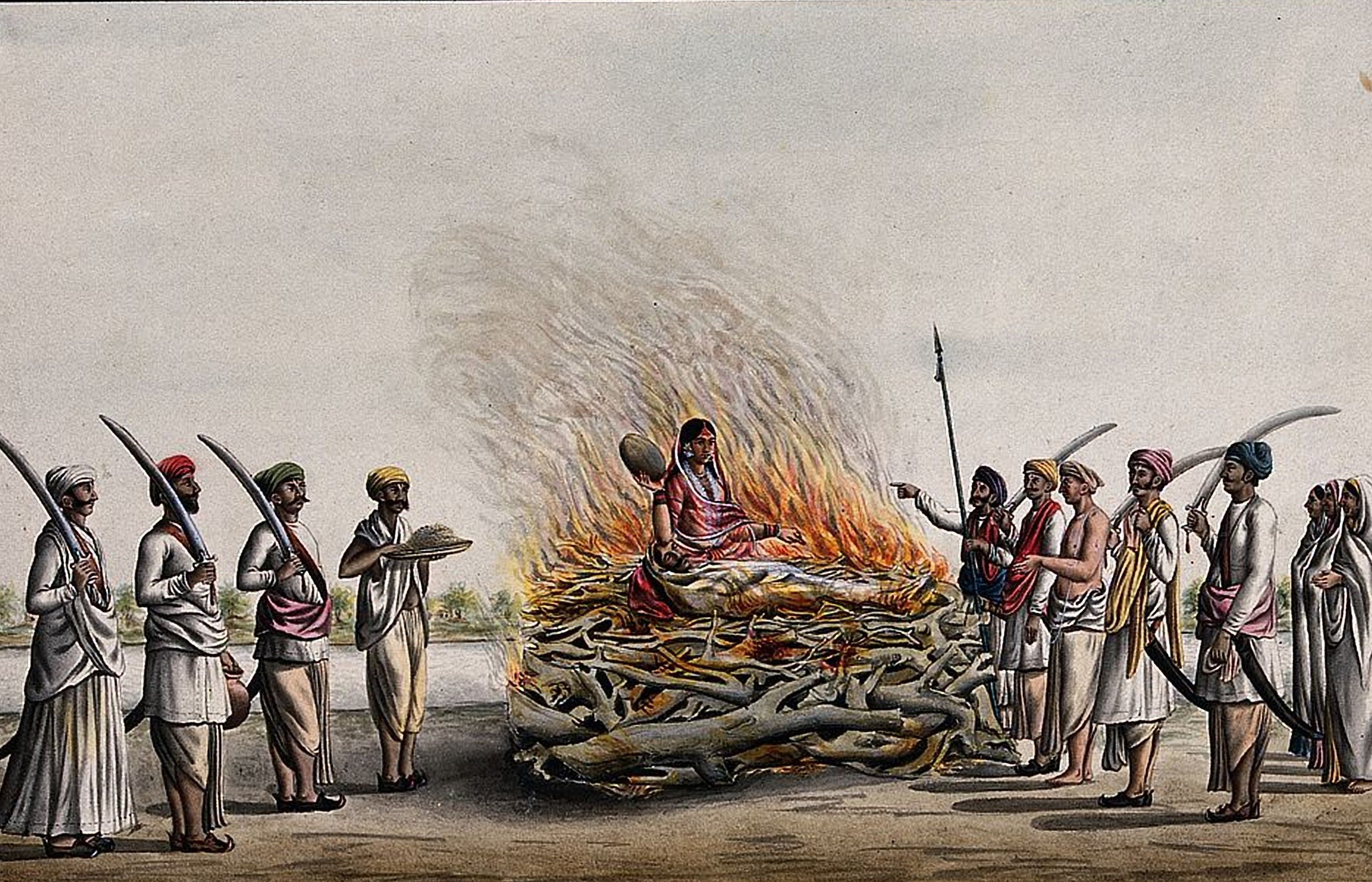

For a myth to prosper, a ritual validated by a religious population is required so as to avert any sign of transgression. The patriarchy myth in India survives on the ritualistic objectification of women where they are reduced to mere sites of creation, they are taught to sacrifice their bodies for them to be heard. Puranas and folk tales have always tried to bind women’s bodies in the hymns of patriarchy. Sati‘s self-immolation to voice her disagreement at the treatment of her husband Shiva by her father, Daksha is well-known. Many different versions are available, reasoning the clash of egos of the patriarch, but at the end of those, the self-immolation of Sati is one segment that remains constant. This act of self-immolation is seen as an attempt to voice her discontentment of the behavior of either. Her body is the subject of her father’s protection when unmarried, and her husband’s ownership after getting married. The body that she never has any right over becomes the ‘other’ that must be sacrificed through self-immolation when she wants to voice a protest.

Also read: How Did Sati Get Abolished In India?

Sati‘s self-immolation to voice her disagreement at the treatment of her husband Shiva by her father, Daksha is well-known. Many different versions are available, reasoning the clash of egos of the patriarch, but at the end of those, the self-immolation of Sati is one segment that remains constant.

Padma Purana explains Sita’s Agnipareeksha: Her husband had given his ‘real’ wife to the fire to be kept safely, and what Ravana abducted was merely an illusion (Maya). Sita unapologetically proved her purity by entering the flames, which can be read as an act of self-immolation yet again, creating her body as a separate entity that can be corrupted. Draupadi was born of fire, a dark princess emerging from the flames to avenge her father’s insult. Her body was constructed to serve her father’s ambitions by marrying five brothers. Mahabharat, a saga that eventually subjects Draupadi to numerous episodes of harassment, after each of which she would find herself standing in a court of patriarchs demanding justice. Padmini of Chittor performed Johar, a voluntary act of self-immolation, an act of preserving her body from being corrupted by any foreign touch. Suffice to say, a woman’s body in the rituals has been constructed as a site of myth, a layer that is not her own. The ‘otherness’ of a woman’s body inspires her to burn it, as an attempt to be heard in a man’s world. Centuries have spent their intellect on fettering the woman in her manifested body, the site of her purification and corruption, a site of family’s honor, and a site to voice her protest.

Woman’s body is how she communicates with patriarchy, by veiling it or exposing it she tries to express herself and when left unheard, she attempts to burn the bridge of communication through acts like self-immolation.

On July 30, 2020, in another act of self-immolation, a woman tried to burn herself to protest the destruction of the standing crops in her field, in Dewas of Madhya Pradesh. She soon became a social media spectacle and politics faded her voice and actual concern. The opposition party blamed the government for encroaching on her land and pushing her over the edge, the Dewas DC alleged her husband to have put her on fire to obstruct government work of paving a way through her agricultural field. Through the contrasting submissions of the men, was a woman, burnt!

Lata Mani in her book ‘Contentious Traditions: The Debate on Sati in Colonial India’ finds fault in the very construction of efforts against Satipratha. She explains how women were never included in the debates concerning their body and their right to live. A woman’s body has been discoursed in colonial courts and experts brought, but never a woman. Self-immolation had always been an intrinsic part of the mythology, but the twenty-first-century woman has turned the table and started using the tool of oppression as her voice of protest.

Also read: The Troubling Truth Behind “Stove Burst Accidents” And Women Burn Survivors

Self-immolation had always been an intrinsic part of the mythology, but the twenty-first-century woman has turned the table and started using the tool of oppression as her voice of protest.

The body that was never her own, is turned to ashes to get the attention of her patriarch counterparts. Lucknow’s evening of witnessing two women’s self-immolation and resultant burning on its streets is a political statement made to question the seams of a society that is bursting with the arrogance of not letting the marginalised sections have a voice. The cases of self-immolation come from the parts of society that are margins of the margins, they belong to either the financially weak sections or lower castes, the doubly oppressed, the subalterns. The situations when the women decide on self-immolation must be treated as separate and significant narratives of protest. They are no more the subalterns who can’t speak, but the few who have turned the tool of oppression to their weapon of protest. In the act of self-immolation is a final emphatic, assertion of one’s ownership of their body, until which it unfortunately is appropriated by patriarchal narratives that deem it a site of pollution, rape, and oppression.

Featured Image Source: Ancient Origins

About the author(s)

Dr. Guni Vats is an Assistant Professor at the Department of English, Manav Rachna International Institute of Research and Studies. A PhD in Gender Studies, she is a renowned researcher, writer, and scholar.