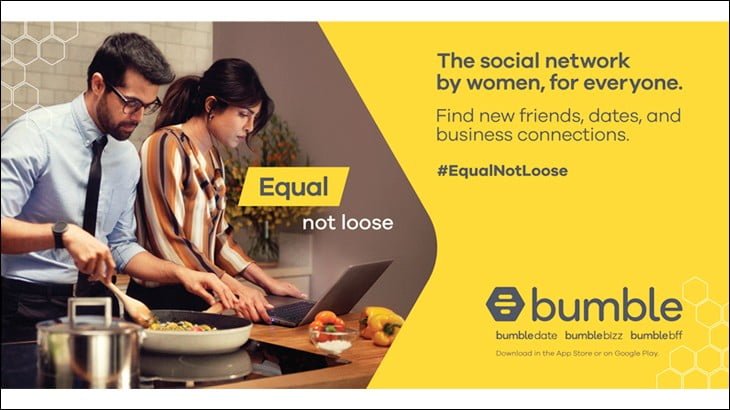

We live in a world, where everything from groceries to love, can be found online. Apps such as Tinder, Bumble, Hinge etc., have spearheaded the process of finding love, both freely and universally. Bumble, the brainchild of Whitney Wolfe Herd revolutionised the online dating app industry by claiming to be the world’s first “feminist” dating and networking app. Herd, formerly the co-founder of Tinder, found herself in a position that compelled her to start her own company, as a result of the gender based discrimination and harassment she faced at Tinder. In Bumble, she found an opportunity to reverse the wrongs done to her.

Bumble, much like Tinder and other dating apps, operates via an algorithm that requires users to put in their personal information, genders, sexual orientation and pictures, and provides them with a pool of people to choose from, within a set distance and location. A right swipe is for when users want to make a connection with the significant other, and a left swipe indicates rejection. If two users match with each other, they can begin a conversation.

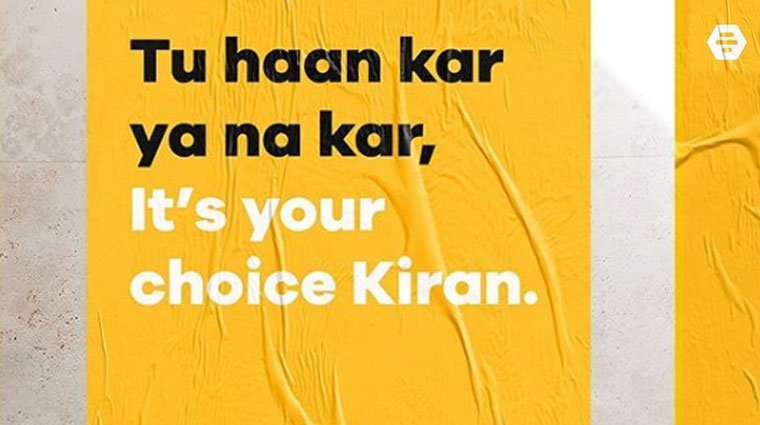

What makes Bumble stand out, is the ‘women text first’ feature in heterosexual equations. But when it comes to same sex equations, either party can initiate the conversation. Many people have seen this as an empowering feature for women, that inadvertently gives them an upper hand in the conversation initiation process, perhaps because they can pick and choose who to text and who not to text. Interestingly, if no texts are sent by women within 24 hours, the match expires, and the conversation window is suspended. It is perhaps this ’empowering feature’ that drove Bumble to market itself as a ‘feminist’ app.

What makes Bumble stand out, is the ‘women text first’ feature in heterosexual equations. But when it comes to same sex equations, either party can initiate the conversation. Many people have seen this as an empowering feature for women, that inadvertently gives them an upper hand in the conversation initiation process, perhaps because they can pick and choose who to text and who not to text.

How does the idea of women taking charge of initiating a conversation with their significant others fit into the paradigm of feminism?

Some feel that this provides a certain level of power or agency to women, in their process of decision making. To others, it symbolises the shattering of certain gender stereotypes that believe that only men should make the first move. This feature perhaps creates an illusionary element of empowerment by making women feel that they are in a position of power, at least temporarily.

The flipside to this however, is that in India women who are “forward” are often seen as “easy” or are repeatedly slut-shamed, for their ‘go-getter’ nature. So, in this sense, the illusion of empowerment falls short. Interestingly, this idea will also find a place for itself in the context of consent, where after having taken charge of the conversation, if the woman withdraws her consent midway, the men on the other end also deploy misogyny via derogatory name calling.

Also read: Disabling Tinder: Online Dating For Women With Disabilties

The debates around Bumble and its ‘feminist’ agendas, have thrown open to me a Pandora’s box full of questions. A trinket from the box however, is consent.

What is consent in the online dating app world?

Is it simply a right swipe that signifies consent to initiate relationships?

Or is consent shrouded in the act of conversation making?

To many, consent is automatically granted when two people match; however, the ambiguity surrounding the idea of consent might persist. At first, consent is perhaps given, for either party to initiate a conversation. But, as numbers and Instagram handles are exchanged, glimpses into each other’s lives are made possible, with the prospect of late night phone or video calls until it is time to meet in person.

Where does one decide, that consent is to be given?

Is consent for chatting also consent for meeting?

Dating apps are bridled with ambiguity surrounding consent, where most often than not, consent comes and goes. One might feel comfortable enough to start a relationship with the other person, but in the process of learning about the latter, they might withdraw the consent they had earlier granted. This ties in well with the question that is the fact that, are women in heterosexual equations, who are entitled to text first truly empowered?

In the context of same sex relationships, there is no underlying assumption that a said party will be the oppressor and the other the oppressed. In fact, it is only after a significant amount of interaction and mutual understanding that this dynamic emerges. So, in this context, consent is towered over by the shadow of ambiguity as well.

If we come to think of it, the reason that women have been entrusted with this prerogative, is that between heterosexual men and heterosexual women, it is the women who are considered to be more susceptible to assault and harassment as most women have at least once in their lives received sleazy texts and unsolicited images without consent. Is the notion of women being allowed to text first in any way going to curb the probability of assault? No. As once the conversation has begun, the ambiguity of consent arises. This idea also manifests itself in the context of how in heterosexual relationships, it is assumed that in most situations, the man is the oppressor and the woman the oppressed, which to a great extent is true; however where does this hierarchy lie with respect to same sex relationships?

In the context of same sex relationships, there is no underlying assumption that a said party will be the oppressor and the other the oppressed. In fact, it is only after a significant amount of interaction and mutual understanding that this dynamic emerges. So, in this context, consent is towered over by the shadow of ambiguity as well.

Also read: How Grindr, The Dating App Is Destroying My Mental Health

While Bumble’s efforts towards appearing and marketing itself as a ‘feminist’ app need to be acknowledged, a deeper re-evaluation of its policies, structures and algorithm needs to be carried out, to fulfil the claim that it is feminist.

Featured Image Source: Law Street Journal

About the author(s)

Janhavi Sharma is a gender, history and food enthusiast and recently graduated from the Young India Fellowship at Ashoka University. She wants to study Gender and Sexuality for her master’s and wants to travel to Azerbaijan. She is an ardent feminist and aims to make a difference within the discourse of academia.