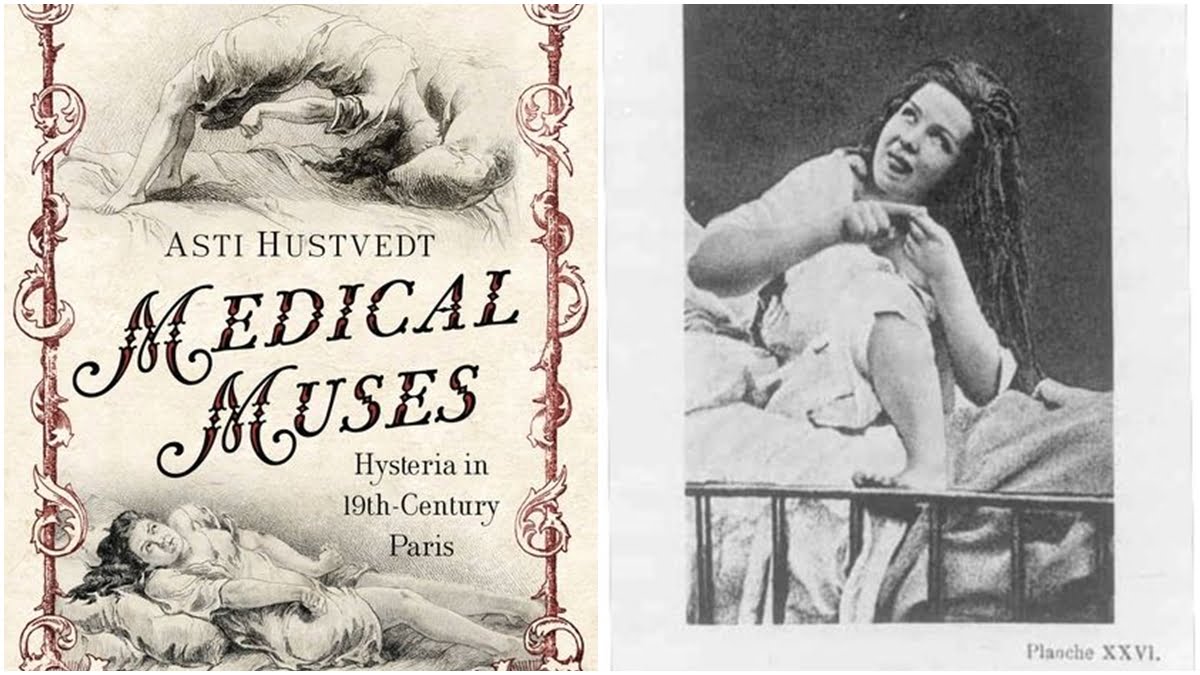

Medical Muses: Hysteria in Nineteenth-century Paris written by Asti Hustvedt was a serendipitous find at the Shakespeare & Company bookstore in Paris when I was loitering around it on a sunny afternoon in April 2019. If not for the chance encounter, I would have missed the book, its riveting content, the pulsating impact of its archival drive and the coincidence of location. Medical Muses goes back to the nineteenth-century epidemic of hysteria in the Paris of the era, compiling material from municipal archives, hospital records, memoirs, intimate letters and popular speculations around the disease to narrate its meandering trajectories through three patients who ended up gaining recognition as ‘celebrities’ while housed in the psychiatric ward of the Salpêtrière Hospital, which was exhumed from academic collapse when neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot took over and introduced facilities and curricula to ensure otherwise. Medical Muses‘ narrative focus on the women bespeaks an empathy on the part of the author, which has been lacking in historical recitations of hysteria; it is the fissures in the accounts, their dualities, contradictions and rejection of cognitive closure that makes the book an engaging read for anyone interested in dissecting a past otherwise divided into a neat exploiter-victim binary bracket.

Also read: The History Of ‘Hysteria’ And How Science Can Be Sexist

In the famous tableau portrait, A Clinical Lesson at the Salpêtrière (1887) by André Brouillet, Charcot is engaged in a demonstration of one of his hysteric patients with a group of curious onlookers and students—all men. The patient, a woman, is highlighted as a vulnerable body in the dishevelment of her attire (per the sartorial appropriate-ness of the era) and unconscious reliance on the body of another doctor for support. The painting is erotically suggestive in its voyeuristic impulse, and depicts an arrested vignette of what was a routine occurrence at the Hospital. The woman’s name was Blanche Wittmann, we are told.

This is one of the many examples in Medical Muses where the author ascribes names to the hysterics and furthermore, acknowledges their respective histories, culled from a range of close and disparate sources. Excavated from the anonymity assigned to these figures from canonical importance attached to the shared illness that enveloped their stories, the hysterics—Blanche, Augustine and Genevieve—are the eponymous medical muses in the Salpêtrière.

Blanche gained visibility owing to her adherence to (and impeccable demonstration of) the medical symptomology of hysteria (as developed over years from observation through sketches and textual accounts), Augustine through her photogenic capacity to evoke personhood (away from strict clinical intention), and Genevieve through her ability to merge neurosis with religious ecstasy (a major area of contention then amongst powerful male circles of authority). Blanche was also the ideal choice for demonstrations of hypnotism, which was used by the doctors not to treat patients, but to induce symptoms for study under controlled conditions; such a strategy conveniently erased the agency of the actor. Under a hypnotic trance, Blanche could be easily persuaded to become a dog or a bird, or even undress; the sexually provocative positions were often euphemistically labelled and recorded as “passionate poses”. Each of the three cases is studied with great attention to detail and presented with enlightening perspective and empathy in Medical Muses. The ‘stars’ became so through an exercise in appropriation of their own afflictions, where their conduct begot rewards for being model patients—not unlike how ideals of feminine beauty as strategies of a capitalist consumer culture become aspirations for like embodiment. In Medical Muses, Hustvedt thus argues that the institution’s focus was never on if, how or when the hysterics could be cured, but whether they demonstrated the symptoms as ideal specimens of the illness for the ulterior motive of (androcentric) academic perusal.

Also read: Tracking The Painful Credibility Deficit Of Women

In Medical Muses, Hustvedt thus argues that the institution’s focus was never on if, how or when the hysterics could be cured, but whether they demonstrated the symptoms as ideal specimens of the illness for the ulterior motive of (androcentric) academic perusal.

The perspective of Medical Muses could be called revisionist, one which argues that the history of the (now deemed pejorative) illness was the result of a complex matrix of exploitation, curiosity, participation, internalisation and circumstances of the specific contexts (of the patients) and era. Everything in Medical Muses—starting from the descriptions of the hysterics’ symptoms to the doctors’ engagement with them as informed by a fundamentally unequal dynamic of power—is compounded by the knowledge that the ‘illness’ of hysteria was without a biological source. Although the mind was suggested as a psychogenic source by Charcot (before the advent of Sigmund Freud with his formative theory of psychoanalysis), it wasn’t enough to support the large body of varying studies done on patients of hysteria, who were predominantly women. Furthermore, Charcot, despite insisting that hysteria issued not from the ‘wandering womb’ (a residual belief from the preceding centuries) but neurons, nevertheless located the source in the ovaries, thus implying that the disease was still essentially female. It was conjectured that the disease was a result of trauma in males while in women, it could be triggered without a plausible origin.

Ovarian compressions (conducted using an arcane tool that looks as appalling as its purported function sounds) worked successfully on patients under attack, hypnosis produced anaesthesia to the extent that the patient didn’t feel even a needle passing through her arm (during extreme experiments conducted by their doctors), and crutches (to allay hemi-anaesthesia resulting from hysterical fits) were abandoned following a (reluctant) engagement with the Christian enthusiasm in ‘miracle cures’ by the hospital—the reluctance issuing from their perpetual hostility with the clerics who deemed science and medicine an anathema to their cause. Medical Muses makes a case for the possibility that there was a larger force working behind this complex intersection of religion, medicine and patriarchy, where the cultures of the time responded to its occupying bodies and their currents. In an era when women had next to no power in the social realm outside the hetero-patriarchal perimeter of the family, claiming sacred possession, for instance, was a way of claiming respectable status and/or authority. This is not to say that the patients never actually suffered the attacks, and we may be indulging in retrospective blindness were we to debunk hysteria from the vantage point of modern medicine by labelling it schizophrenia, anorexia or like disorders (recognised by the DSM taxonomy), which hysteria resembled in its symptoms. The author, in tandem with Charcot, never doubts the ‘reality’ of the illnesses the women were suffering from, but questions, excavates, and studies the circumstances that might have bred them.

Medical Muses makes a case for the possibility that there was a larger force working behind this complex intersection of religion, medicine and patriarchy, where the cultures of the time responded to its occupying bodies and their currents. In an era when women had next to no power in the social realm outside the hetero-patriarchal perimeter of the family, claiming sacred possession, for instance, was a way of claiming respectable status and/or authority.

Medical Muses focuses on the subversive aspects of hysteria while studying its potential and active mobilisation as spectacle. The star-patients were painted, sculpted and fictionalised in novels. There are mentions in Medical Muses of actresses attending Charcot’s public demonstrations of hysteric patients to absorb tips for corresponding embodiment (especially gestures of collapse) that could be transferred from the context of the amphitheatre in Salpêtrière to the grandeur of romantic overtures on the cinema screen when the strong male body was an exciting visual receptacle for the delicate damsel. Public carnivals mushroomed, where amateur hypnotists attempted to imitate Charcot’s demonstrations in independent capacities (called ‘cabinet shows’ after the grand reveal of the hysteric body enabled by the box), simulating the spectacle for the mass audience that readily consumed the fare in exchange of money. There’s a story of a hysteric who escaped the hospital disguised in drag (then against the law and not just frowned upon), and another who walked across cities by foot and slept in jungles while foraging for food after escaping from the ward. There’s also the story of a patient who recounted and insisted on abuse by a Salpêtrière doctor who perhaps took advantage of the general doubt around the veracity of her words to continue the exploitation without detection or punitive threat. Sexual liaisons between patients and employees were common, but there was also a corresponding imbalance and lack of consent in these interactions, especially in light of the knowledge that hypnotism could be used to exploit female bodies without the latter consciously remembering the trauma.

Sexual liaisons between patients and employees were common, but there was also a corresponding imbalance and lack of consent in these interactions, especially in light of the knowledge that hypnotism could be used to exploit female bodies without the latter consciously remembering the trauma.

But were the women totally helpless before their anatomy? Patients could withhold their symptoms from occurrence out of spite for the doctors, reports Medical Muses. They were a demographic of “diseased, uneducated and lower-class women” for whom the space of the hospital was marginally better than the stifling conditions of the world outside. The reproductive body was mystified in its power to create life as much as it was relegated to the realm of the abject when it deviated from normative expectations. Their symptoms were often coping mechanisms and acts of resistance against a system that dubbed the deviant either a saint or a witch and accorded them like treatment. True, the history of hysteria is one of misogyny, but it cannot be viewed through the lens of a one-way traffic; the women were not always passive victims of male clinical attention. The women recognised power in their sexual difference, which they then used to galvanise a subversive affinity with the illness. Their contorted body was both a desirable spectacle and annihilatory threat to the patriarchy.

True, the history of hysteria is one of misogyny, but it cannot be viewed through the lens of a one-way traffic; the women were not always passive victims of male clinical attention. The medical muses recognised power in their sexual difference, which they then used to galvanise a subversive affinity with the illness. Their contorted body was both a desirable spectacle and annihilatory threat to the patriarchy.

Hustvedt talks about illnesses that could serve as contemporary analogues to hysteria (such as chronic fatigue and the Gulf War syndrome) that exist without apparent biomarkers, arguing that the absence of tangible symptoms, and the fact that they predominantly affect female bodies, still remains a cause for perusal and popular skepticism (even dismissal of their authenticity). The medical climate in the nineteenth century was one that held space for the illness through intensive study, where ‘outcasts’ were accommodated in a logic of rehabilitation that necessitated a performative compulsion. Hysteria was both a need and refusal to assimilate. Their very status as ‘muse’ was essentially a male anointment where conformity was rewarded. We would do a disservice to the hysterics by calling them pure victims of the patriarchy; they participated in the reciprocal logic of the illness and its study, and actively shaped the extant script from the century as a meandering, ultimately indecipherable and elusive text. The photographs and illustrations of Charcot’s patients remain in currency today as residue of and portals to a history of psychosomatic experiences; the illness remains ultimately irreducible to a singular diagnosis of the repressions of the era and its bodies.

Also read: How Psychology Wronged Women

Hustvedt argues that hysteria was primarily “an illness of being a woman in an era that strictly limited female roles”. We would be dishonest to ourselves if we claimed that this statement didn’t hold true for us even today. Vocal women such as US Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (better known as AOC) are deemed hysteric in the right-wing press for simply speaking their minds with clarity and without undue appeasement to male figures of authority. That clarity may be accompanied by a visible rage, which does not make their statements any less legitimate. Hannah Gatsby channelises this rage through searing comedy that admits no self-deprecation, and cuts through congealed gendered prejudice using the same tool—art history—that has served to shape the female body as image for centuries through an objectifying male gaze. Rebecca Traister points out that the act and sight of a woman “opening her mouth with volume and assured force, often in complaint, is coded in our minds as ugly”. These women have then enabled a powerful shift in perspective, the visibilisation of their rage validating allied emotions in less public figures. It is both a personal and political anger that issues from a sustained and relentless dismissal, trivialisation, infantilisation and vilification of female rage by peers and institutions alike.

We carry the weight of this historical pain in our bodies. Black women, white women, women of colour, Muslim women, Dalit women, trans-women and other bodies that have been historically marginalised through mutating forms of a systemic oppression, carry a cumulative weight of rage that stems from multiple binds of repression that vary with context and climate, the invariable thread being that of our assigned sex or encoded gender. We sometimes swallow our anger and it eats us up from the inside, diminishing potential possibilities to flourish in other directions. Some of us organise our furies around the status quo so they don’t tear us apart. Some of us give up and finally vocalise it because every instance of repression now causes nausea. Some of us yell into the face of denial despite the constant, discouraging invisibility, which renders us hoarse. And some of us just don’t give a damn anymore. Hysteria, as an illness unto itself, has probably dissipated in its exact nosology, but persisted in the form of a physical agony whose source had historically originated outside the immediate body—in a patriarchal matrix of desire and control, leaving only its impact inside the host. Both the illness of hysteria and its current iterations (that circulate in overt isolation from their etymology) betray a pervasive fear of female sexuality and agency.

Anger is insight, says Audre Lorde. Understanding anger is a means to understanding the frightening nature of unadulterated fury that renders it ‘hysteric’ in the popular eye. It helps us make sense of an immobilisation and numbness caused by the shared trauma of a collective body; my anger is then a historically belated reaction. Women’s anger has shaped our histories and that of activism and art. I think of activists Shehla Rashid, photojournalist Masrat Zahra and the many women who have raged against the incumbent government (often literally in the faces of hyper-aggressive male reporters) and been vocal about the plight of Kashmir against the toxic Hindutva regime despite institutional pressure. I think of Shaheen Bagh and the Muslim women who stepped out of the domestic ambit onto the streets in the biting Delhi winter in protest of the xenophobic Citizenship Amendment Act, and occupied them day in and out in civil resistance to fascist strategies of erasure. I think of the #Metoo movement and the many voices that left whisper networks and verbalised their narratives of abuse. The movement rippled across continents in pulsating vibrations of rage, disrupting longstanding hierarchies of power that privileged the male body. When systems of justice (itself a patriarchal construct) seemed elusive, it was anger that established the veracity of their experiences. The anger was (and still is) raw, profane and burning; rage leaks. There are stark reminders of our daily embattlement as women everywhere, and men think our fury is fiction.

One can hear Blanche laughing in her grave.

An independent researcher, Najrin Islam is a postgraduate from the School of Arts and Aesthetics, JNU. Working as a freelance writer and editor, she takes interest in performance, cinema and archival studies with a lens on marginal histories. She can be found on Facebook, Instagram and writes regularly on her work blog.