Posted by Manmeet Kaur

When working with young girls in government secondary schools and discussing intersectionality, I often share a personal example of overlapping identities. As a woman, feminist, and practicing the faith of Sikh, my relationship to my body hair is dictated by at least three different identities. It is one of the rare intersections where my religious and feminist identity, partly coincide. During the course of these workshops with the girls, I take up two of my identities fairly often. For my lack of critical engagement with my own religious identity, it gets left out of the mix.

Feminism’s engagement with religion and faith has always been fraught with a complicated sense of distance. The personality of its practice, and the fragility of its interpretation makes it difficult to initiate critical dialogue which is usually possible where patriarchy is otherwise concerned. This complex engagement was the subject of Feminist Multilogues’ first session on Faith and Feminism. The discussion was led by Dr Uma Chakravarti, Dr Syeda Hameed, and moderated by Kamla Bhasin.

Feminism’s engagement with religion and faith has always been fraught with a complicated sense of distance. The personality of its practice, and the fragility of its interpretation makes it difficult to initiate critical dialogue which is usually possible where patriarchy is otherwise concerned.

Also read: Sangat & Feminist Multilogues Webinar: On Questions Of Caste & Gender Within Religion

Dr Uma Chakravarti started her talk by laying bare the reasons behind the complexity of feminist questioning of religion: she argued that religion came together in a package with culture and patriarchy, and it was almost impossible to completely separate these out, to the extent that they inform each other.

As all panelists hail from the first generation of Indian feminism, she described the inherent “unease” this generation had with faith and religion and questions of the “spirit”, enmeshed as it was with gender inequality. This reluctance is exacerbated by the “thekedaars” of religion, mostly men, who have a vested interest in upholding hierarchical social relationships.

As a feminist historian, Dr Uma shared insights on the chronology of this enmeshing: patriarchy was well in place before faith and religions like Hinduism started to take shape, thus arriving in an already patriarchal setup.

As a feminist historian, Dr Uma shared insights on the chronology of this enmeshing: patriarchy was well in place before religions like Hinduism started to take shape, thus arriving in an already patriarchal setup. Moreover, it is difficult to extract women’s criticism of religion, as the circulation of knowledge has also been largely controlled by these “thekedaars”.

Dr Uma illustrated her arguments with examples from Buddhism and the Bhakti tradition. The formation of Buddhism was within a patriarchal setup, centered on the celibate male monk, denying women’s entry into the system. She also shared the story of Ananda, Buddha’s first cousin who pleaded the case of Buddha’s foster mother to enter the Sanghas, and succeeded after much debate with the Buddha. A very insightful narration of the tradition of Bhikkhunis followed, and the rejection of confinement of women to the kitchen they embodied. She spoke lyrically of the world of spirit and expansion of self which these women now inhabited, leaving behind the life of the “grinding stone”.

Dr Uma then moved on to discuss examples of experimentation in the 19thcentury, the stories of religious conversion of Pandita Ramabai and Urmila Pawar, laced with an important observation–the rebellion against the establishment and concretisation of unequal religious ideals is as old as the ideas themselves. It’s not like men have always agreed with the upholding of these ideals either: there have been significant oppositions and alternative interpretations of firm systems, structures, and ideas which have come from men.

The feminist history and political perspective was followed by Syeda Hameed’s recounting of her personal relationship with Islam. Quoting verses from the Quran and drawing on her own experiences, Syeda laid out the understanding of Islam that currently exists at large, and the possibilities of textual interpretation. Sharing her journey of growing up in a religious but secular household, she quoted from the Quran on there being no compulsion in religion. She also shared her rediscovery of her relationship with the religion at a difficult time in her life, drawing again on the Quran on Allah being closer to the human being than their jugular vein itself.

Syeda spent some time discussing the misinterpretation and notions which exist regarding gender inequality and Islam, being completely opposite of her understanding of Islam’s proclamation of equality much ahead of its times. She also shared snippets from the fourth surah of the Quran, the second longest surah of the holy book, being all about the right of women.

Syeda Hameed’s own endeavor of drafting the Nation’s first Status of the Muslim Women’s report, and being the first woman Qazi to perform a Nikah ceremony, was a telling experience in understanding and narrating the lives of Muslim women, and their dual tussle with intra religious forces, and preconceived notions regarding the faith and religion of Islam.

Also read: Session On Contemporary Dilemmas In Feminism By Nivedita Menon

Syeda’s personal journey and negotiations with gender and religion, especially as a political figure made for a fascinating insight. The two Maulanas, whom she counts amongst her mentors, wrote and talked extensively about the gentle face of Islam. Syeda’s own endeavor of drafting the Nation’s first Status of the Muslim Women’s report, and being the first woman Qazi to perform a Nikah ceremony, was a telling experience in understanding and narrating the lives of Muslim women, and their dual tussle with intra religious forces, and preconceived notions regarding Islam.

Syeda herself gave many examples of revered women in the Islamic tradition like the Prophet’s daughter, Fatima and granddaughter Zaynab. The tragedy of understanding in knowledge, according to Syeda, lay in the halt of interpretation in Islam, which made newer cultural and spatial readings of the texts impossible, and blasphemous.

Kamla Bhasin’s talk in the session was an overarching conclusion, which summed up the significance of religion in the current times–personally and professionally. The role it plays in shaping one’s identity may be a personal experience, but the one it plays in shaping the larger cultural narrative, public life, and spaces is undeniably strong, collective, and political.

One of the most remarkable insights I personally gained from the session was the difference between the textual religion and the one in practice. Tying in beautifully with Uma’s first observations, Kamla Bhasin’s words formed the perfect conclusion to the trinity of patriarchy, culture, and religion, which make any singular critique incomplete, and rather impossible.

The personal occupation of a religious space, the first intention of a religious text, and the practice of religion in its current form can all take vastly different faces, and still continue to be done ‘in the name of God’, and sometimes, the same God.

The process of coming to terms with an identity one inherited is possibly always a tough one. I have experienced this once before in letting feminism allow me to figure out what being a girl and a woman meant to me. This hasn’t changed much in what exists outside of my understanding of my womanhood, but it has helped me navigate this dissonance better.

With positive dialogue and debate restarting in the realm of religion, it is possible that I will soon be able to greet girls in senior secondary schools with a more wholesome truth about my own identities–but that is work in progress for now, god willing.

Manmeet Kaur leads Gender and Equity programmes for an Indian education non profit. She is an English literature graduate from Lady Shri Ram College for Women, Delhi University, and has a Masters in Gender and Development from Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex, UK. She loves to combine feminist thought and concepts with storytelling and creative expression, and is an active member of the Delhi One Billion Rising team, a global movement against gender based violence. She can be found on LinkedIn.

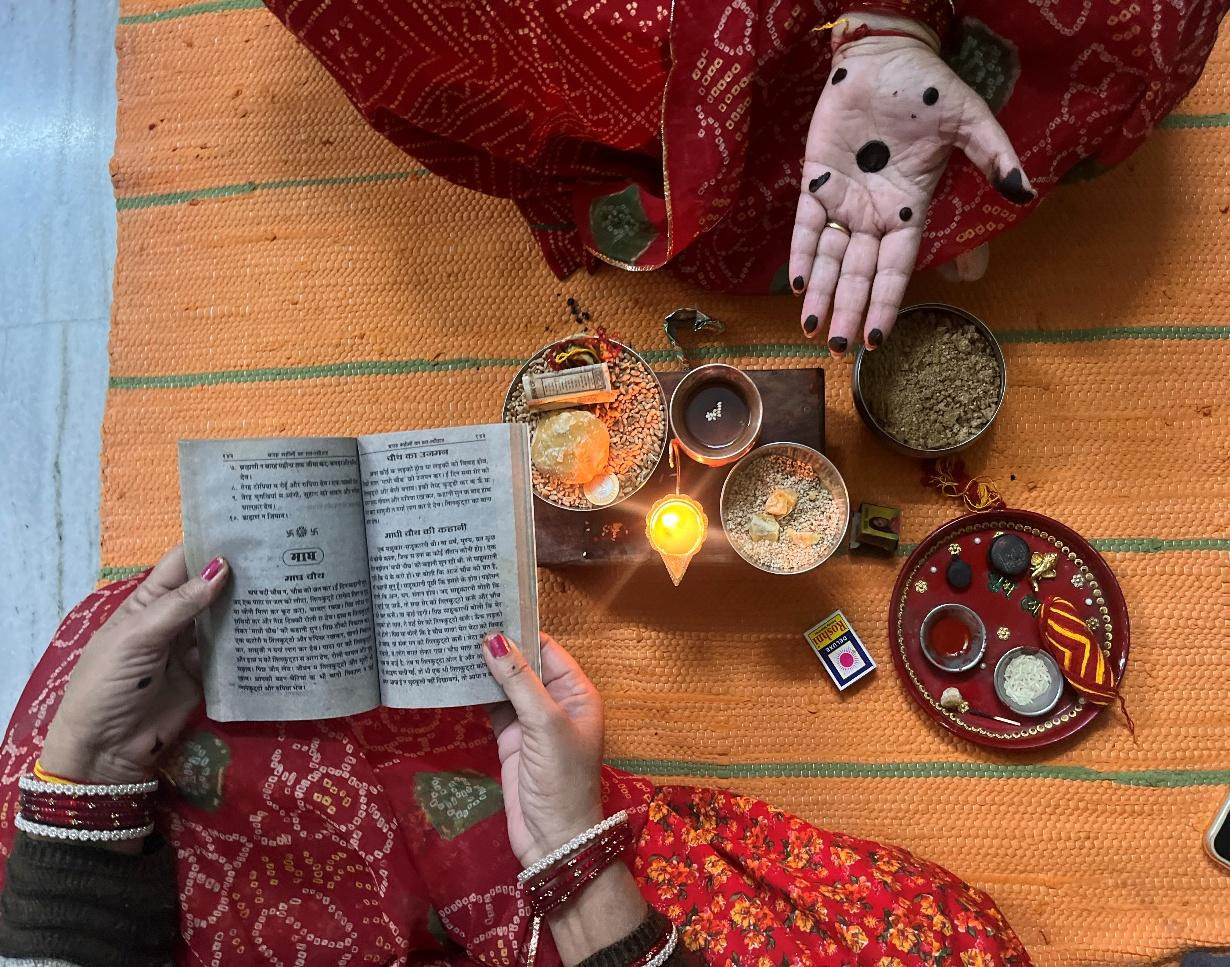

Featured Image Source: Facebook

About the author(s)

Sangat is a network of organisations and individuals working towards building and strengthening regional feminist solidarity through capacity building, campaigning and promotion of feminist culture.