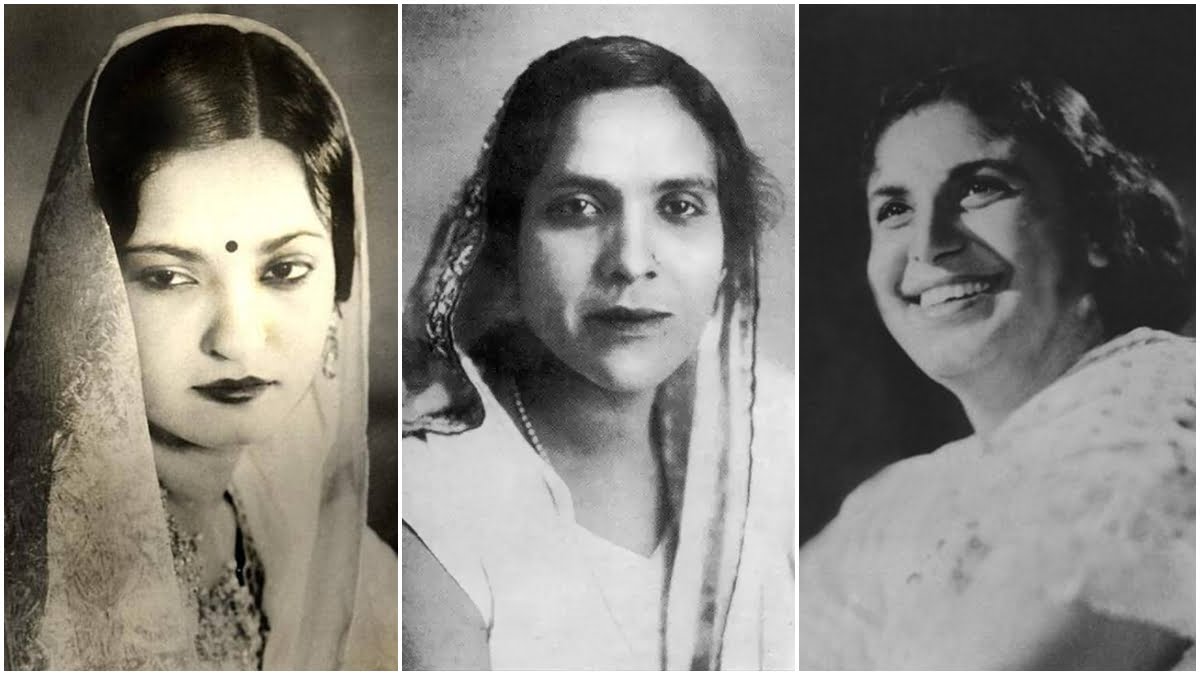

In the 1940s-60s, many women from the community of courtesans (also known as tawaifs) joined the Indian film industry, which was still dominated by film-makers from foreign nations. These women set many milestones in the industry and established legacies that are alive till date, even if the artistic culture of tawaifs is not.

However, the story of tawaifs and their free-spirited endeavours in the film industry took a darker turn as India’s independence appeared imminent. As the nation woke up to its future, it chose to leave many aspects of its past behind.

The story of tawaifs and their free-spirited endeavours in the film industry took a darker turn as India’s independence appeared imminent. As the nation woke up to its future, it chose to leave many aspects of its past behind.

Also read: When Cinema Came Calling For Tawaifs: Leaving For Bombay Part I

Yours Nacheez

Appreciation of Indian classical music often feels insincere, no matter how deeply felt. The intricate grammar of this style only reveals itself to the trained ear. The layperson has to often make peace with just the emotional import of the music. Despite the rough sound of the YouTube version of Gauhar Jaan’s Ghoomar, it manages to produce an overwhelming feeling of astonishment. How does a voice flow like hers, seemingly unfettered by physiological restrictions?

Gauhar Jaan was a wealthy courtesan in Kolkata, born to Badi Malka Jaan. Her voice inspired the teenage Akhtari Bai Faizabadi, whose voice had garnered Vijayalakshmi Pandit’s appreciation, to abandon her cinema dreams and anchor her music career in classical traditions. Faizabadi was a hereditary courtesan or a tawaif. In those days, tawaifs were associated with the Muslim elite. Scholars say that a man was not considered to be ‘polished’ if he had never visited a tawaif.

Pre-independence India may have been home to highly respected courtesan-performers who were talent powerhouses, but the cultural reimagination that accompanied India’s independence turned this around. After independence, a campaign was launched against tawaifs. Their kothis were closed and the national broadcaster, All India Radio, refused to allow them on its programs. It was famously said that people whose “private lives were public scandals” would not be allowed on AIR, and this sentiment side-lined all hereditary performers.

Faizabadi at this time was the opulent leading figure of Lucknow’s music. Lucknow residents reminisce misty-eyed the times when she would ride in her Packard, dressed in diamonds, smoking a cigarette. The years leading up to the independence put her position in jeopardy, as a deluge of public condemnation seemed imminent.

What solved this was a man’s shadow.

In 1945, Akhtari Bai Faizabadi married Ishtiaq Abbasi, a barrister who met her at a performance. This is when she came to be known as Begum Akhtar. Contrary to what one may think at first blush, she was not forced into this. In her own words–

“You can love a good person as much as you want, But when he loves you too, there is nothing else you want.“

Scholars have debated incessantly about the idea of choice, and how choices are often only an illusion created to convince a person that they retain at least an iota of agency over their lives. Was Begum Akhtar’s choice really her choice?

These lines, said to her student Rekha Surya, throw a little bit of light-

“You must have a man’s shadow over your life. You are young and beautiful; they will not let you live in this world of singing. You will simply have to get married.”

Tawaifs like Begum Akhtar simply had to get married in those times to restore a smidgen of the respect they got in their previous, yet current lives. Begum Akhtar’s own marriage into a respectable family could have opened the door to independent India’s world of music.

However, she was forbidden from singing by her husband for five years, till her mother’s death made her so inconsolable that only singing could heal it. It is hard to miss the dramatic value of this moment. Public memory about Begum Akhtar is shrouded in an air of mystery and fascination, and one wonders if this event is also simply a product of a vigorous imagination.

Nevertheless, her debut on AIR (1949) caused an explosion of demand for her singing. She performed in concerts across the length and breadth of the nation, cut records, and even sang for films. Few vocalists in India have been celebrated the way Begum Akhtar has been, joining the likes of Lata Mangeshkar, Mohammad Rafi, and Kishore Kumar.

She is now known as Mallika-e-Ghazal (Queen of Ghazals) and is the face of the Nawabs’ cultural exports to their future.

Turns out, this wasn’t enough for a woman in her time to set her own rules for her home. Begum Akhtar was forbidden from singing in Lucknow, for she was to remain in the city as Barrister Abbasi’s wife. Visitors remember that Begum Akhtar would not as much as even recite a poem in her house. She had been ostracised by the women of her husband’s family, whom she showered with gifts to win their love.

In the public sphere, Begum Akhtar was a luminary. But in the private sphere, she continued to be what she used to sign off her letters as – yours nacheez (nothing).

Begum Akhtar’s later years were a lonely time to be a woman in semi-classical music. However, her early years saw a lot of women from similar artistic backgrounds introduce films to music that is cherished even today.

Making Airwaves

Ila Arun played a small role in the recent feature film Manto, which perhaps went unnoticed in front of Nawazuddin Siddiqui and Nandita Das’ stellar performances. However, her character, Jaddanbai, is a personality whose life could have warranted a film in itself, had it been better documented.

Jaddanbai was the daughter of Daleepadevi, a courtesan who was kidnapped by a band of traveling performers in her childhood. Her career began with recording ghazals for various companies. Eventually, she got her first film break in Raja Gopichand (1933) as an actress. She acted in a couple of films before establishing her studio.

With this, Jaddanbai became an institution in her own right, even if it was what we will today call nepotistic. Her studio produced the film Talashe Haq, which starred her six-year-old daughter Nargis. Talashe Haq (1935) featured Jaddanbai as a producer, film composer, and actress. She also went on to direct films.

Also read: How ‘The Last Courtesan Of Bombay’ Destigmatises Tawaifs And Mujras

Jaddanbai’s sphere of influence extended to her home. She was the sole breadwinner of her family, and she demanded that her husband change his religion to Islam to marry her. The family switched between Islam and Hinduism at will, with Jaddanbai using her alternate name Jayanti Devi at times.

Jaddanbai was one of India’s two earliest female composers. The other one, Khorshed Minocher-Homji, graduated from Bhatkhande Music Institute in the 1920s. Begum Akhtar had grown up in the area where this college is.

V.N. Bhatkhande played a major role in altering both this land and its musical culture to suit the nationalist narrative. Bhatkhande believed in restoring traditional forms of music–their classical variant, which according to him had been polluted by the ‘new artists’, predominantly Muslims and women. Bhatkhande College was named after him.

Homji thus did not belong to the now disrespected tawaif tradition, but she had other problems. She and her sister sang in the immensely popular show Homji Sisters on AIR. Her voice got noticed by Himanshu Rai, whose Bombay Talkies shaped Hindi films as we know them. Her first hit film was Rai’s Acchut Kanya (1936), featuring Ashok Kumar and Devika Rani. This was the first Hindi talkie film.

This was enough to make the Parsi community seethe in anger. In response to their outrage at a Parsee woman being shameless enough to sing publicly, Rai was forced to conceal Homji’s identity and give her the name Saraswati Devi. Saraswati Devi, along with Jaddanbai, was the first in a field that lacked a female voice up until Usha Khanna’s debut as a composer twenty years later.

Saraswati Devi gave her last film score in 1961. By then, the expansive influence of hereditary performers in Indian arts had been restricted to museums, history textbooks, and the roving memories of the elderly, who had seen tawaifs perform in their youth.

Saraswati Devi gave her last film score in 1961. By then, the expansive influence of hereditary performers in Indian arts had been restricted to museums, history textbooks, and the roving memories of the elderly, who had seen tawaifs perform in their youth.

In cities like Lucknow, Kolkata, and Delhi, the lives of tawaifs became uncertain stories that changed every time they were discussed in the streets. The tawaif tradition eventually vanished completely-leaving behind ruins in Old Delhi and a new performing arts tradition in Mumbai.

Disha is a permanent resident of Wikipedia rabbit-holes and a firm believer in the power of boring things. She is an Economics Graduate from Lady Shri Ram College. She can be found on LinkedIn.