Published by Shruti Parikh and Yashi Jain

Over the last six months, the COVID-19 pandemic has simultaneously triggered economic, social, and health crises all at once, in addition to recurring crises and natural disasters like the Amphan Cyclone, floods in Assam, crop destructions, and more. While many communities and population groups in India suffer from this burden, marginalised or vulnerable demographics disproportionately bear the burden of crises.

Women and girls comprise of one such group. As the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak has been far and wide, the harsh reality that marginalised women and girls in our country are a disadvantaged population group has become more visible. The effects of such vulnerabilities are only further compounded by a state of recurring crises.

Women and girls comprise of one such group. As the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak has been far and wide, the harsh reality that marginalised women and girls in our country are a disadvantaged population group has become more visible. The effects of such vulnerabilities are only further compounded by a state of recurring crises.

However, this is not a new problem – a look back at past examples shows us that women and girls in India have been sitting on the fences of such recurring crises for far longer than just the past 6 months.

Reflecting on times of crisis in India over the past decade, some trends observed among vulnerable populations and practices adopted by civil society and governments reveal systemic breakpoints, needs and solutions for women and girls. As we seek to reinvent and rebuild our society, economy, programs and policy to overcome and recover from the impacts of COVID, India’s history of crisis presents learnings on important considerations, effective solutions, and gender-equitable practices that we can take forward into the coming decade.

This article is an attempt at documenting past and recurring crises, highlighting gaps that continue to exist, and identifying learnings which are relevant and applicable to our efforts today. It is contextualized to gender-based disadvantages and aims to recommend ways for government, communities and civil society organizations to build a balanced, gender-equitable and crisis-resilient society post-COVID.

The next time a crisis, or like in the case of the last 5 months – crises, hit, we hope for gender inequality to have become one less thing to worry about.

Also read: Bihar Floods: Extreme Weather Events Are Not Gender-Neutral

2018: The Nipah Virus presents a Public Health Crisis

While the current pandemic is unprecedented in scale, severity and impact, there are important lessons we can draw from past outbreaks and recurring crises such as the Nipah virus outbreak in Kerala in 2018. The Nipah virus was first seen in Malaysia in the late 90s and in Bangladesh and West Bengal in the early 2000s. The virus, although not very efficient, is communicable through contact with a very sick patient, making it very similar in nature to the corona virus. During the time that the Nipah outbreak was spreading in Kerala, it claimed 17 lives.

Many credit the government’s swift action for this relatively low mortality and prompt containment of the virus.

Cut to 2020, Kerala was one of the forerunners in the response to the COVID-19 crisis in India. KK Shailaja, Minister of Health and Social Welfare, Kerala, credited Nipah virus learnings for their quick response to COVID-19. In fact, she was recently honoured by the UN.

Reflecting on parallels we can draw, similar to the case in 2018, it was the Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) workers, who are some of the most respected and empowered women in rural communities, that emerged as the real warriors. Unfortunately, what seems to have failed to carry forward from the Nipah outbreak was the value, compensation and recognition for India’s frontline workers.

ASHAs, mainly women, play a key role in the health system by working closely with communities to shape attitudes, awareness levels, health response and preparedness, and systemic accountability in the regions in which they work. Today, ASHA workers continue to be at the frontlines but are still paid inadequately in comparison to their spectrum efforts, their working conditions which are unsafe and unregulated, as seen in reports from the lockdown stating shortage of PPE equipment for them, and they continue to be overburdened with multiple public responsibilities ranging from election duties to relief and response.

So how can we change this moving forward?

First, there is a clear need to revisit the financial incentive structure for front line workers and better compensate them. Additionally, it is critical that they be given appropriate protective equipment to perform their responsibilities without risking the health and well-being of their own families.

Increasing incentives, appreciation and financial stability for ASHAs and other women in such roles is one priority intervention to ensure our frontline response remains strong and economically inclusive. We explore economic inclusivity for women further below, but the need of the hour is to recognise the value of labour that women continue to put into the caregiving industry and support it with financial incentives.

Second, we need to unburden our health force by decentralising and distributing the burden of healthcare instead of a standardised central solution. Decentralisation of solutions worked well for Kerala during the Nipah crisis. A group of over 26,000 ASHA workers responded in tandem with the community and the local public health system to deploy a two-fold approach, creating a robust database of every household and implementing the ‘trace-test-isolate-support’ strategy during the 2018 outbreak.

Hence, equal distribution of responsibilities, localised effective solutions, and economic inclusivity could strengthen and incentivize the health workforce, especially for women.

November 2016: India’s Economic Crisis Sparked by Demonetization

One of the boldest economic moves of the past decade took place in 2016, when PM Narendra Modi declared 500 and 1000-rupee notes to be invalid in order to eradicate ‘black money’ from the economy. The consequences and the impact of the move has been highly debated ever since.

According to a UN report, 80 percent of women in India in 2015 saved money in cash and did not have bank accounts. For many, these cash reserves provided a measure of independence and security, acting as a safety net to escape violence or to feed their children when family funds were low. For others, the savings were a means to fulfill desires that would otherwise not be acceptable at home.

During demonetisation, when all piggy banks at homes had to be forcefully broken, it forced many women back into family savings pools, exposing the limited and easily-lost financial independence of women in society.

Women were also the worst hit in the unemployment wave that followed. As cash went out of the system, the informal economy that accounts for 45 percent of India’s GDP and employs 80 percent of the Indian workforce was left in shambles, leading to many of the unskilled women dependent on this economy unemployed.

To put this in perspective, reports indicate that 5 million men in the informal sector lost their employment and that women were hit far worse. Even though the working-age population of women increased from 2016-19 (44.1 to 47.1 crore), the number of women in the labour force had decreased (7.41 to 5.23 crores).

Today in the wake of COVID-19, we see a similar story unfolding. Families are facing a cash crunch and loss of income. The informal labour market and migrant workforce have been exposed to the harshest realities, and yet again women and youth have been the most affected.

Reflecting on 4 years since demonetisation, there are various lessons we can learn on mitigating such financial risks for women:

The most important lesson from demonetisation is the need to empower women financially and get everyone on an equal financial footing. After demonetisation, it was found that the percentage of women with bank accounts increased to 77 percent (Findex Survey 2017) from 53 percent in 2014.

Unfortunately, this didn’t translate to a holistic inclusion and parity. Despite the establishment of bank accounts, the active use and participation of women in lending and transacting practices through these accounts were low. A culmination of various socio-cultural mindset and disadvantages ultimately lend to low awareness, confidence and demand for financial inclusion for women.

Another need that is pressing is the inclusion of women in the formal economy through intentional and immediate special provisions and measures. Economic exclusion has a direct correlation to safety, agency and social equality for women. Gender gaps like these, if closed, could lead to a 27 percent increase in India’s GDP.

India currently ranks 120th among 131 countries on women participation in the workforce, our Female Labour Force Participation (FLFP) has been falling over the last two decades. The work that most women do daily, tirelessly is “unpaid”, resulting in Indian women working seven times more on unpaid work than Indian men.

The need to normalise the equal distribution of unpaid work, as well as including women in the formal economy couldn’t be more glaring.

If we want to emerge out of the pandemic without economic bruises, the need to put on a gender lens is immediate. Financial inclusion and a foot in the door for women in the formal economy through equal distribution of work stemming from a change in cultural attitude is the way forward.

Be it a social, health or a natural crisis, a common thread to the road to empowerment for women is financial inclusion and independence.

2014-2017: India’s young women face a social crisis as rates of early and illegal marriage are on a steady incline

History suggests that there are visible spikes in child, forced and early marriage immediately after times of crisis and disaster. For example, child marriage was observed to increase immediately after the 2004 tsunami and after the Ebola outbreak in the early 2000s.

A similar effect is expected as a result of this year’s pandemic, which is putting an estimated 4 million more girls at risk of interrupted education, loss of essential services and agency and forced/early marriage and trafficking.

While the situation sounds bleak there are always ways to overcome it. Understanding what worked in the Indian context in the past might provide us with an effective way forward to keeping child marriage on the decline –

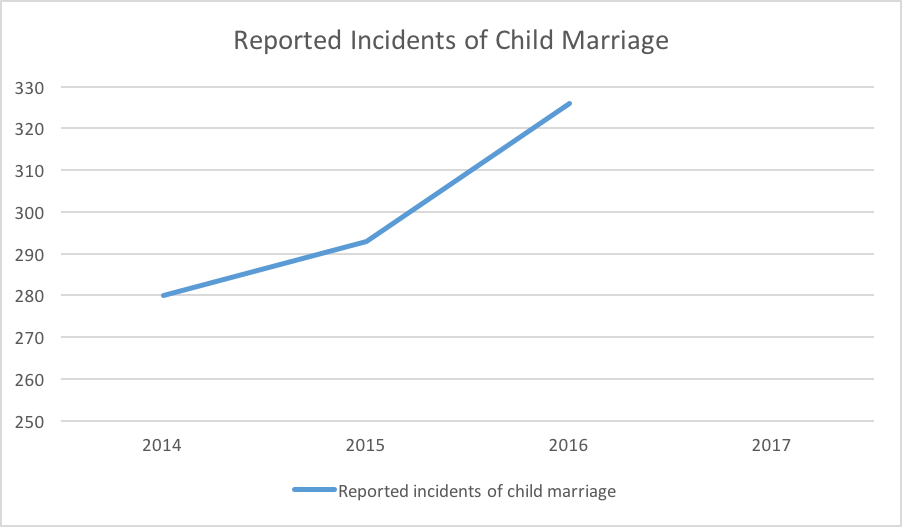

As recently as from 2014-2017, India reported a steady annual increase in child marriage cases. Reported incidents of child marriage went from 280 in 2014, to 293 cases in 2015, to at least 326 cases in 2016.

Using this time period as an example to learn from, we see that addressing its root causes and determinants can be effective to reduce child marriage, but also that sustaining interventions are important to avoid reversal of any gains made.

Child marriage is an outcome of the interplay of many social, economic, behavioural, religious and infrastructural factors. Economic pressures, extreme poverty, and the idea that girls cannot contribute financially often lead to situations in which girls are rushed and sometimes sold out of their homes at young ages through arranged marriages. Worse, they often are given no choice in who and when they marry.

When education and livelihoods are interrupted, it can lead to girls being prompted to leave their homes under the guise of finding jobs in cities, only to be trafficked into unsafe situations. COVID-19 has intensified nearly all these factors, while also breaking down safety structures around early marriage.

Frontline workers, who are usually key in reporting and preventing early marriage, are already overburdened and unable to give significant attention to the issue. Similarly, with schools closed, teachers and principals have been unable to flag unusual absences – often an early indicator of an impending marriage.

The nationwide lockdown has left many girls excluded from mobile and digital communication, reporting channels, and local safe spaces and peer groups. Further, the intensification of life at home and household responsibilities has reinforced patriarchal behaviours that lower society’s ideas of the value of girls.

As the government currently explores ways to combat child marriage through legal action around the legal age of marriage, the following are key levers that have worked in the past to control and reduce child marriage:

Evidence suggests that ensuring that education, technology, and informational services remain accessible to women is effective in maintaining girls’ agency and self-worth, value in society, and support networks, thereby having a direct correlation to lower risk of child marriage.

There are many interventions that can help in the continuation of these essential services. For example, extending the right to free and compulsory education up to at least age 16, ensuring well-monitored distribution of cash incentives for girls completing education and abiding by the legal age for marriage, finding localised and resilient ways to keep girls informed and connected through IVRS, helplines, leveraging local police, etc.

Some of these considerations are relevant especially in the context of the Ministry of Human Resource Development’s New Education Policy.

Second, the issue of child marriage in India is very contextualised to social and cultural factors. These, however, vary from state to state. Tackling child marriage has proven more effective when solutions are decentralised.

For example, despite the introduction of a National Action Plan to prevent child marriage in 2013, major movement on preventing child marriage was seen once state-level action plans, such as the Strategy and Action Plan for the Prevention of Child Marriage in 2017, came into play.

Therefore, as we try to mitigate the several risks that COVID-19 presents, it will be important to drive and maintain accountability among state governments to create and deliver localised protection from child marriage.

Finally, early marriage will continue to be a risk while anti-female biases and gender inequality are still prevalent in society. As we rebuild our economy post-COVID, we need to sustain advocacy for greater representation and inclusion of women in the formal economy and workforce, narrative change for women and girls to one in which they have agency and independent decision-making power, and attitude shifts around the value and dignity of women and girls such that they are no longer viewed as financial burdens.

In the last 17 years, India has faced over 300 recurring crises like natural disasters, including floods, cyclones droughts, landslides, and earthquakes. Available data from these disasters shows that women and girls are more likely to die in the aftermath of a disaster.

2013: Flash floods in Uttarakhand disproportionately affect Women, especially in post-disaster recovery

In the last 17 years, India has faced over 300 recurring crises like natural disasters, including floods, cyclones droughts, landslides, and earthquakes. Available data from these disasters shows that women and girls are more likely to die in the aftermath of a disaster.

Having less access to resources like education, health, psychosocial and financial services left women dependent, trapped and unable to exercise agency. Owing to a de-prioritisation of girls from a very young age, many women had not built survival skills like swimming or disaster response, leaving them little chance of survival.

Today, amidst a pandemic and in an already resource-crunched situation, many vulnerable communities are also having to face the effects of extreme flooding such as in Assam and Mumbai and cyclones like the Amphan cyclone in West Bengal.

One particular natural disaster to learn from is the flash floods in Uttarakhand in 2013. Over 4000 people died of casualties and over 2500 houses were destroyed.

Women and girls were left significantly disadvantaged, mostly due to pre-existing systemic and societal disadvantages against them. The floods also led to a housing crisis, leaving many without safe water, sanitation, hygiene and shelter, which directly impacted women’s safety and their sexual, reproductive, and menstrual health and left them more susceptible to assault.

However, the government of Uttarakhand responded with a women-centric and gender-focused plan and achieved significant progress and restoration as a result. Many approaches from the 2013 response remain relevant even today:

Women were involved in an ‘Owner Driven Construction of Houses’ methodology, whereby they rebuilt their own disaster-resilient homes with the support and oversight of technical partners and NGOs. This not only empowered women to take charge of their own welfare, but also left them with new skills, increased resilience, and direct communication channels with local non-profits and social services that could guide them on their rights, benefits and opportunities.

Further, a women-centric lens prompted the government to address open defecation and safety and health issues. Of the 2500 houses destroyed, 2400 have been rebuilt with private toilets. In Uttarakhand, 10 percent of the rebuilt homes are now led by a matriarch.

As we rebuild to recover from the impacts of COVID, giving voice to the most-affected groups who understand the breakpoints in the system best is non-negotiable. Empowering women to participate in the creation and delivery of solutions for their own welfare is necessary.

Many of the successes achieved in 2013 were possible because of the availability of gender-disaggregated data. In Uttarakhand, a theme-based gender analysis was leveraged along with the regular Damage and Needs Assessment that is conducted post-disaster. Ensuring policy and decision-makers have a detailed understanding of the state of girls and women is key to promoting a much-needed gender lens to the design and implementation of solutions for the most vulnerable.

Lastly, over half the women affected in the 2013 flash floods were given bank accounts and full control over relief and rebuilding installments transferred to them, allowing them to have equitable say and control over their post-disaster lives. Once again, financial empowerment and inclusion of women is a priority and effective strategy for the way forward, as a learning from the recurring crises we have witnessed so far.

Also read: California Wildfires: How Heatwaves Are A Human Rights Concern As Well

2020: India juggles a public health, social, economic and natural disaster together in the midst of a COVID-induced nationwide lockdown

The impact that the COVID-19 outreach has on India is far too visible and intense to be ignored. It has exposed gaps in our infrastructure, shortcomings in our public awareness, unfairness and inequity in our economy and workforce.

If we are intentional enough, learnings from our history of dealing with recurring crises can give us hope and the possibility of a more resilient future. Most overdue, we need to place a strong emphasis on gender inclusion and equality for the way forward. Women and girls need to be included and empowered in solutioning and decision making; to be given proper and independent access to financial resources; to be appreciated and equitably compensated for their work, be it formal or informal; to be able to easily access information and access on health, hygiene, safety, and rights; and to be valued as competent and contributing equals and leaders in society.

The coming year will likely see governments, communities, non-profits and welfare groups, philanthropists and more working with a common priority – rebuilding and restoring India’s society, economy and infrastructure. We mustn’t do this without strong gender-focused coordination, gender-intentionality, and the steadily increasing inclusion of women and girls across all contexts.

Only then can we begin to imagine a post-COVID world that will be better prepared to deal with recurring crises and COVID-like situation in the future.

Featured Image Source: Deeply

About the author(s)

Dasra is catalyzing India's strategic philanthropy movement to transform a billion lives with dignity and equity. In 1999, Dasra was founded on the simple premise that supporting non-profits in their growth will scale their impact on the vulnerable lives they serve. Dasra accelerates social change by driving collaborative action and powerful partnerships with funders, social enterprises and other key stakeholders.