Nazariya QFRG organised Our Lives Our Tales (OLOT), a series of talks by queer people and fought battles for the queer movement, as a way of preserving and passing along oral narratives of historic moments that might otherwise would have been lost. Through the webinar series that took place in June 2020, Nazariya documented and shared the journey of the LBT*Q collectives Sappho for Equality, Stree Sangam/LABIA, Vikalp, and LesBit/Rahi.

Through the webinar series that took place in June 2020, Nazariya documented and shared the journey of the LBT*Q collectives Sappho for Equality, Stree Sangam/LABIA, Vikalp, and LesBit/Rahi.

This is a summary of the report by Nazariya. For the full report, click here.

In Search of a Community

Shals Mahajan, the founder of LABIA: A Queer Feminist LBT Collective, talked about how they had once came across an article in the newspaper about a gay conference at SNDT Women’s University and connected with the then director to put her in touch with ‘other dykes’. A young and brash Shals, as they recall themselves to be, would not take no for an answer and eventually got Aarti’s number. Aarti and Sakina were the known lesbian women in 1995’s Bombay, through which others connected.

Shals added that this was a time when the term ‘queer’ was not part of the vocabulary. After meeting Aarti, Shals was soon introduced to others and suddenly for the first time ever, they found themselves in a room in India, full of only queer people like them.

Also read: Queer History: How Did Queer Women Network Before The Age Of Internet?

After organising a small meetup at Aksa beach, the group soon began ‘Stree Sangam’. Networking with Forum, India Centre for Human Rights and Law, and others that were not seen as queer, helped relax their anxiety of being outed. Stree Sangam also organised the first national retreat in Bombay, in 1996, followed by a second in 1998. Friends from Delhi and Kolkata joined in.

Writer and queer activist Maya Sharma was also part of this retreat and remembers it to be an important event because it was the first time, a national level gathering of queer people took place.

There was no agenda for the retreat, the folks were invited to share their lived experiences and get to know each other. Chayanika, Physics lecturer and feminist, queer and civil rights activist, expressed the joy they felt in being part of two important moments.

These were important moments indeed, given the lack of discourse or space to articulate queerness at feminist conferences, even a few years later. At a conference in Panchgani, held in December 2000, Maya recollected deciding to share her field experiences with the queer people’s community. This news reached the trade union she was a part of, much earlier than the conference was set to begin. Even though Maya spoke in her own individual capacity, she was asked to leave the Union and did so in the next six months.

In conversations on domestic violence by women’s groups, there have largely been no talk on and around queer people and Sunil Mohan has confronted this exclusion. Recognising how queer people’s concerns were separated from those of women’s groups, Sunil began to organise talk sessions with many individuals on various topics, from ‘love and violence’ to ‘acid attacks’.

In conversations on domestic violence by women’s groups, there have largely been no talk on and around queer people and Sunil Mohan has confronted this exclusion. Sunil was the Kerala State Women’s cricket team captain. He published reports such as Towards Gender Inclusivity and Conversations on Caste Discrimination in South India and has worked on the oral history documentation of LGBTI people in South India.

Recognising how queer people’s concerns were separated from those of women’s groups, Sunil began to organise talk sessions with many individuals on various topics, from ‘love and violence’ to ‘acid attacks’.

Even within the gay community, lesbian and bisexual women saw a need to carve out their own space. Despite the general niceness of people at the Council Club, a gay organisation, Malobika and Akanksha, from Sappho For Equality based in Kolkata, could not relate to them as the oppressions they faced as women, as homosexual women, were different and not relatable.

A 1999 Anandabazar Patrika article on Malobika and Akanksha resulted in more than three hundred and fifty letters from women to the postal code shared. Soon enough it was a team of 30 people responding to these letters and on June 20, 1999 Sappho was formed in Malobika and Akanksha’s ten by eleven square feet of a room. Simultaneously, Fire was re-released.

Also Read: Let’s Talk About Alternate Safe Spaces For Queer Women In India

Fire

Fire by Deepa Mehta stirred up controversies upon its release across India because it dared to touch upon the topic of female homosexuality in a conservative society such as that of India’s. It met with a lot of hostility from the right-wing sections in India followed by a ban. The protests to remove that ban brought many queer people together.

Malobika and Akanksha shared their memory of watching and re-watching the movie, then visiting the theatre numerous times to wait outside and gaze at the spectators, in search of people who “look like us”.

Chayanika fondly remembered the special screenings for women spectators in a single screen theatre in Mumbai. Stree Sangam made little four-page long pamphlets with Vijaydan Detha’s version of the Rajasthani folk story of Teeja and Beeja, to circulate at these screenings and in turn, received letters at the Stree Sangam post box. Chayanika added that whether one likes it or not, Fire brought the conversation of female sexuality out in the public eye.

Soon after when the movie was banned by the censor board, Campaign for Lesbian Rights or CALERI was formed bringing together certain women groups and individuals to fight the ban. Maya shared that the campaign’s objective was to spread awareness and carve a space for the community and the issue.

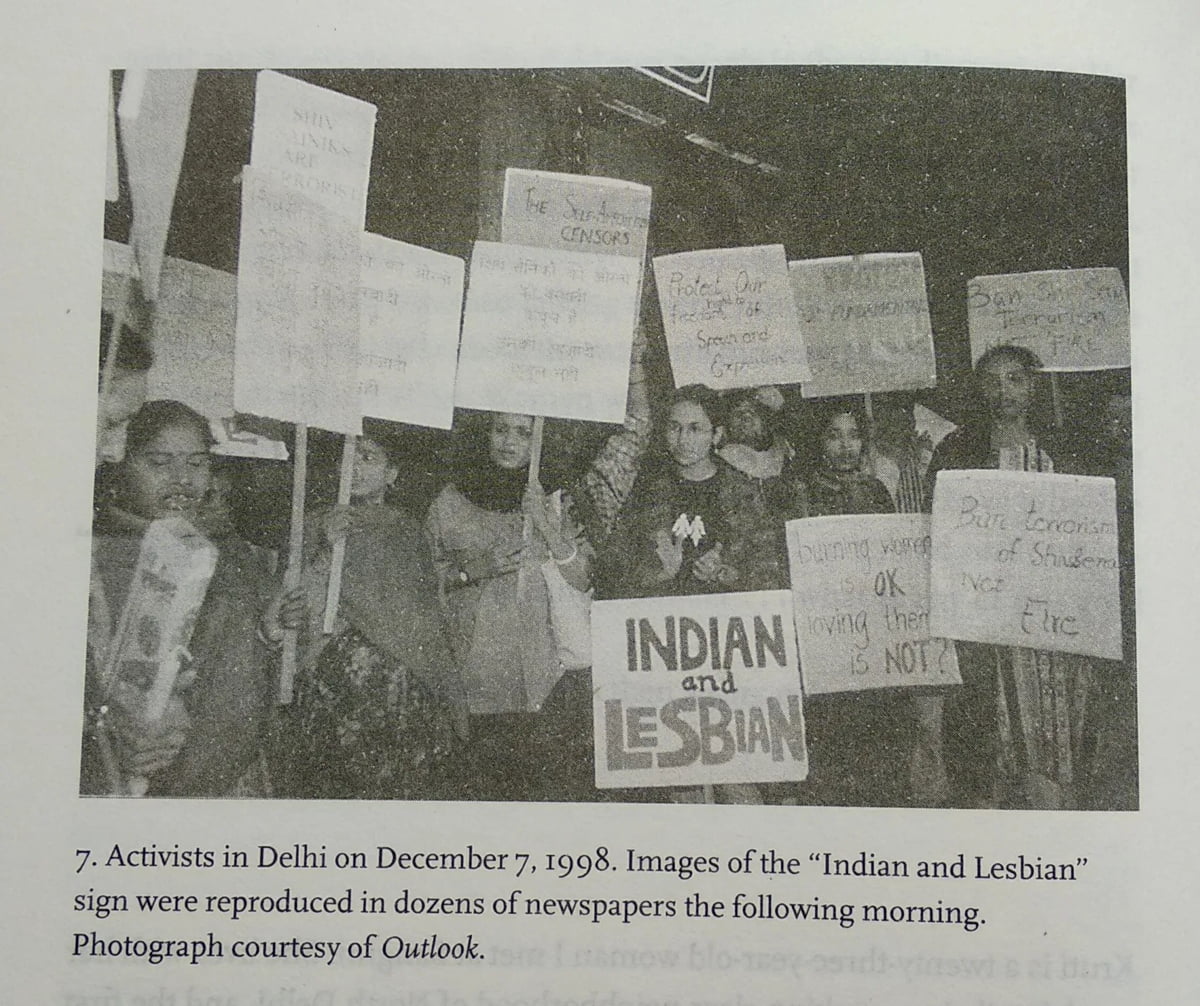

She added that some groups were adamant to take this issue up as a suppression of female sexuality rather than the safer approach advised by most groups then, of viewing it as a violation of freedom of expression, that they only joined the campaign on the condition of it being vocal about women’s sexuality. She recalls making the ‘Indian and Lesbian’ poster to counter the argument that lesbian is a ‘western idea’.

Soon this poster caused a scandal and possibly, Maya stated, became the first visible expression of women’s choice of their sexual expression.

Maithilee currently works at Nazariya QFRG as a programs manager. She can be found on Instagram (@maith.lee), Twitter and LinkedIn.

Featured Image Source: Queer Activism in India – A Story in the Anthropology of Ethics by Naisargi Dave