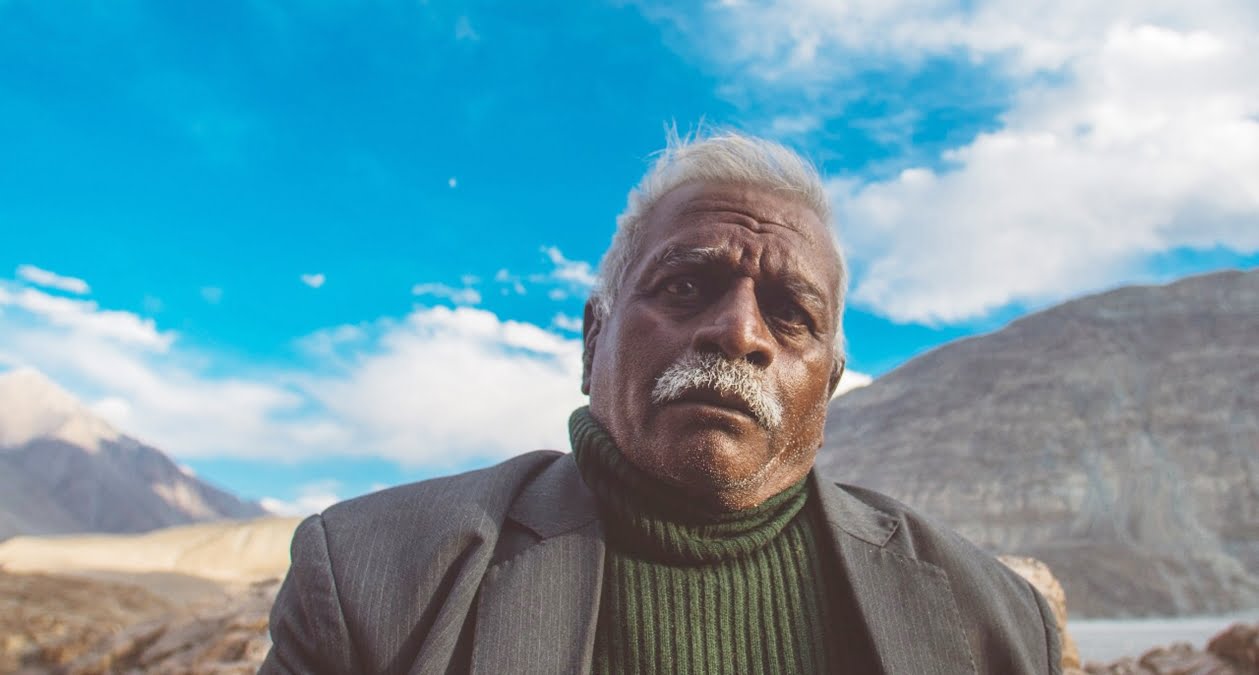

Namdev Bhau is exhausted by modern existence, annoyed by the loud banalities of people going about their lives, themselves caught and ensnaring others into their habitual spheres of being, but he neither entertains nor offers. Namdev Bhau wears the face of someone who has lost interest in life.

Through the film we see him not speaking, not even responding when spoken to. The audience is introduced to the protagonist played by Namdev Gurav, an actual driver with no experience in acting, as he gets woken up by the drunken frolic of his relative and his wife complaining in the background of noises from a nearby train-station and a temple. Namdev Bhau’s first act is to plug his ears with cotton.

Also read: Review: Unlimited Girls–A Viewer’s Guide to Feminism

The audience is introduced to the protagonist played by Namdev Gurav, an actual driver with no experience in acting, as he gets woken up by the drunken frolic of his relative and his wife complaining in the background of noises from a nearby train-station and a temple. Namdev Bhau’s first act is to plug his ears with cotton.

Namdev is a chauffeur who has to spend most of his day on the road working for an elderly lawyer who does not quit speaking. When he is not on the phone, he is singing to himself, telling stories to an uninterested Namdev, or hurling abuses at him. Namdev Bhau comes home to an equally disquiet place. He decides to leave his clamorous hometown of Mumbai to find peace in the silent valley of Ladakh prompted by an article he read about the five most silent places in the world.

To his disgruntlement, the far-away and supposedly isolated cold desert has also imbibed the mind-numbing noises of modern civilisation. To add to his never-ending despair, Namdev Bhau is joined by a twelve-year old boy, the film’s second protagonist, who is in search of his parents in a place called Red Castle. The boy, Aaliq played by Arya Dave, stands in contrast to Namdev. One gets excited by everything, the other has no zeal, one is curious about everything, nothing raises question for the other, one is easy to share, the other wants to be left alone, one keeps chattering and pestering the other with questions while the other looks more annoyed.

The film comments on the popular cliché of liking quiet, everyone from Namdev Bhau’s wife to Aaliq claim in the middle of their never-ceasing chatter that they love silence. It also makes a comment on the celebration of quiet people and how it is only from a distance.

Having such people in your life might give you a not-so-tranquil discomfort as is shown by Namdev’s boss, his wife, Aaliq, and perhaps even us, the audience. The director, Dar Gai, is aware of the negligible amount of dialogues of the protagonist, she is also aware that Namdev Bhau speaks for the first time when almost half of the film is over.

Gai has chosen the child of an inter-caste couple as her second lead, while making her protagonist’s first ever dialogue to be “chicken” spoken to a boy orphaned by honour-killing. Makes you wonder if this is a comment too. Gai has struck the nature of quiet people right, it is not like a mystic poet who opens his mouth only to deliver a divine revelation with speech resembling a calm ocean that the first word is spoken.

It does, however, make you stop not because you are trying to comprehend the wisdom behind, but because it is abrupt, awkward, and new. The Ukrainian filmmaker has knit the story of Namdev Bhau like a double-sided scarf.

When she presents it to you, she keeps on top the escape of a man from the modern drudgeries of a fast-paced metropolis and the banal plagues of people around. We understand that, we relate to it, we chew into our own desires of finding peace somewhere far away from the vexing hullabaloo of cramped human modernity.

And then she lets her not-so curious protagonist help us turn the scarf and see the other side of what was supposed to be a feel-good film. The audience can decide which side to keep on top, both are real, both are popular, one popularly felt, another popularly known and forgotten, one makes us yearn for it and smile with Namdev Bhau, less than a handful number of times that he smiles in the film, the other makes us uncomfortable and makes us want to neglect it.

Women with dialogue in the film are dependent and sources of nuisance to the tired irritable hero, be it his wife or a stranger in the hotel who is too scared to sleep alone in her room. The film’s cinematography runs congruent with the Namdev Bhau’s interested-by-nothing mood. It will show you Ladakh, but don’t go in thinking it will be a tourism ad boasting of Ladakh’s “virgin” beauty.

Namdev Bhau and a few of his local co-passengers on the bus are vexed by the not-virgin-and-quiet-anymore state of Ladakh. Two sides of Ladakh are presented, one uneasy and perturbed by tourism, while kind strangers offer free rides and free food, well not guarded if we must get technical.

The director, who started writing this story due to her own experiences of sensory overload in Mumbai, claims that the first thing a new-comer experiences in the city is noise. It can easily become the only thing they experience. Cinematographer, Aditya Varma, and the sound designers of the film do a brilliant job helping the audience know what is going to dominate their senses in different settings.

In Namdev Bhau’s hometown, we only hear a cacophony of noises, the scene doesn’t give the eyes too much to occupy the brain, but the ears do such that one never having experienced a sensory overload can correctly imagine what it must feel like. In the far-off cold desert, eyes have much to report to the brain.

But the long suffering of Namdev Bhau has left him so wearied that he finds even the sound of howling wind obnoxious. Namdev finds his destination, Silent Valley which is now a tourist spot, intolerable and wonders in murmured anger if the only option left is to go deaf.

As the duo go on and part ways, we see a turn in the misanthropic demeanour of Namdev Bhau. He even smiles and dances, every inch of his body drenched in the awkwardness of first attempts. The film does not ease our own frustration with the enervating by-products of modern civilisation by answering whether there is after all any solace, but it does replace the wide-eyed horror of the protagonist with a quiet content smile.

The film does not ease our own frustration with the enervating by-products of modern civilisation by answering whether there is after all any solace, but it does replace the wide-eyed horror of Namdev Bhau, the protagonist, with a quiet content smile.

As for the orphan of systemic and violent injustice, it makes it the audience’s job to marvel at the mother’s preparedness, be saddened by her knowledge of her and her husband’s impending murder, be spellbound at her success of protecting her child even after death from not only the killers but also trauma. It might also raise the question of why then choose to stay together if they knew that an inter-caste marriage would bring an end to their lives.

Why knowingly put a child at risk of violent orphanhood? Perhaps, it was for love, a demand for freedom, for a life worth living. While it may be difficult to know the answer to this question, it does plainly point out how we find it easier to digest somebody’s irritation from wind than digest somebody’s right to live, not a dignified life, but live period.

Also read: Enola Holmes Review: The Damsel Who Distressed The Patriarchy

Instead of empathy, we have the audacity to be irked and genuinely ask, why then chose to live a worthwhile life? We also have the audacity to call ourselves egalitarians while we wear the un-scarred side of the scarf and on occasions of celebrating our condescension and paternalism, flash the other side and sigh as if our brow is carrying the burden of changing the entire world, “Yeah, caste is a HUGE problem.” And in the the next breath, move on to how peace-giving a “simple” spa treatment can be.

Featured Image Source: IMDB

About the author(s)

Sumaiya Taqdees is a content editor, and a post-graduate in Political Studies from JNU. With a penchant for art, a love for ironies, and an aspiration to become a tree, she is a person of few words except when writing.