The recent Hathras gang rape case created a furore in the mainstream media and on social networks only to highlight an issue that has been staring at us for far too long. In 2020, if we are still having to establish the pervasive nature of caste within our social structures, then our progress as a people is debatable. To the savarna eye, caste may not exist; it is the Dalits (which literally means oppressed or broken) who have felt the sting of this societal and systemic oppression in their bones for thousands of years, and has now translated into what could be referred as the intergenerational Dalit trauma.

The Dalit trauma, oppression and discrimination experienced by members of the community have been multidimensional – from brutal physical, emotional, psychological and sexual abuse to everyday microaggressions, leaving a haunting imprint on the psyches of the people.

The Dalit trauma, oppression and discrimination experienced by members of the community have been multidimensional – from brutal physical, emotional, psychological and sexual abuse to everyday microaggressions, leaving a haunting imprint on the psyches of the people. The sheer volume of abuse and suffering inflicted upon this community due to an organised system of societal stratification at the hands of the ‘upper’ caste individuals has been indiscriminately huge. Privilege allows one to be caste blind, but to deny the suffering and pain of a community that is a perpetual victim of alienation, denigration, discrimination and violence is to shirk away the responsibility of being a part of this society.

Also read: Caste Impunity Vs Legal Protection For The Hathras Rape Victim

Dalit trauma does not fit into the classical definition of trauma, which is defined as the emotional and physical response to a highly distressing event. For the Dalit community, life has been a series of traumatic events of varying degrees, forcing them to live in perpetual survival mode. The nature of Dalit trauma is intergenerational – passed on from one generation to the next, forever altering their psychological, emotional and physical states.

Intergenerational trauma begins with the first generation that is directly impacted by threatening circumstances and suffers post-traumatic stress. It is then passed on to the future generations through secondary traumatisation, experienced in the form of emotional dysregulation, chronic anxiety and high stress levels, intra-community violence, unhealthy attachment styles, and higher levels of physical and mental illnesses.

According to psycho-historian Peter Loewenberg, unconfronted grief or unmanaged trauma is a kind of neuronal “short circuit”, in that it changes the DNA in a way that unconsciously binds the descendants of a traumatised community in collective and unconscious solidarity with the original trauma.

In his work Cultural Trauma and Collective Identity, Jeffery C. Alexander writes “collective, cultural trauma occurs when a group of people feel that the trauma they have endured leaves indelible marks upon their group consciousness, marking their memories forever and changing their future identity in fundamental and irrevocable ways.”

Dalit experience has been fraught with physical, mental, financial and social insecurity; the unfulfillment of these primal needs has triggered a constant sense of anxiety and a strong need for security in the minds of Dalits. Starting with the idea of pollution attached to their identity, Dalit minds were trained to feel a profound sense of shame about who they were and the work they were assigned. This is “learned cultural shame” and it is an intrinsic quality of the contemporary Dalit identity.

Their bodies and their lives didn’t seem to matter, and have been consistently used as a battleground to establish and perpetuate Brahmanical hegemony and power structures dictated by the Hindu caste system. Religion and faith, which constitute a psychological refuge for many, betrayed the Dalit community by pushing them to the literal margins of the society and legitimising the oppression they experienced throughout their lives.

Their voices, their expression, their art have been underrepresented and erased from the face of history, diminishing their identity to the confines of victimhood. The discrimination faced by Dalits isn’t just caste-based; dimensions like religion, nation, gender, and class play a role in determining the form and degree of discrimination.

The intersection of caste and gender is where we get to witness the ugliest facet of caste-based discrimination. The caste system advances by controlling women; by asserting ownership and control over a Dalit woman’s body and reducing it to a tool to maintain power dynamic, savarna men continue to harass and rape Dalit women with impunity. There is no element of lust in this act, it is caste-based gender violence, a statement that serves as a testimony for the uncontested superiority of savarna men and to show Dalits ‘their place’.

According to Ranajit Guha’s definition of a subaltern, Dalit women are impacted by three levels of subordination; “her sex, her poverty, and her caste”. Not only are they subjected to violence by upper caste men, they also suffer abuse at home from their own husbands. The sexual exploitation faced by Dalit women isn’t a feminist issue alone; the element of caste makes it much more intense, degrading and dehumanising. The societal expectation of subservience defines a Dalit woman’s trauma, with her health and wellbeing often compromised and not given enough importance, and the public ownership of her sexuality.

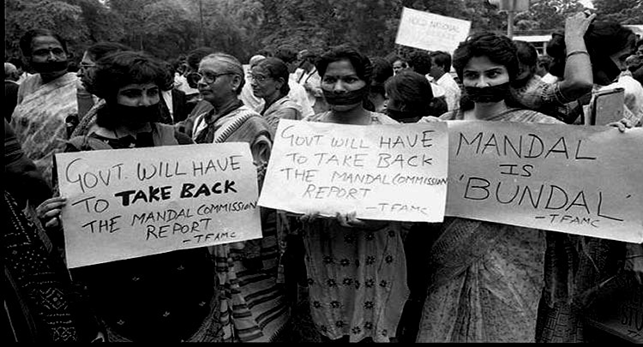

One of the tenets of the caste system is the colonisation of knowledge; Dalits have been deprived of access to knowledge and resources, ancestral wealth and financial security. In 1950, the reservation system and caste-based quotas were established to provide representation to historically and currently disadvantaged groups in Indian society in education, employment and politics.

While it helped advance the quality of lives for many Dalit families, it was marked by an undercurrent of resentment and protest from the upper caste population. Even though they haven’t had the access to a robust social network and resources which is the case for many savarnas, Dalits have harboured an intrinsic sense of shame around their position in these institutions as a “quota candidate” and often suffer discrimination even in professional environments. The fact remains, even at a premier college and studying amongst the most meritorious crowd of the country, the Dalit student feels small and hesitant to assert her presence in the classroom.

To reveal their identity and to ‘come out as a Dalit’ can put their lives at risk at any given time. Today, there is a wider class gap among Dalits because of better access to education and employment. While a major section of the population still struggles to preserve their integrity on an everyday basis and is susceptible to harassment in all shapes and forms, there exists the upper echelon within the Dalit community that is privileged enough to pronounce themselves as equal to a savarna family of similar economic status.

However, that is rarely the case though; caste is a psychological burden for Dalits, so much so that it alters the way they view life. The Dalit trauma that they have inherited and individually endured often results in a low sense of self-esteem, psychological and physical insecurity, a sense of shame and guilt merely for existing, inferiority complex, emotional dysregulation and inability to forge healthy relationships.

The Dalit trauma that many have inherited and individually endured often results in a low sense of self-esteem, psychological and physical insecurity, a sense of shame and guilt merely for existing, inferiority complex, emotional dysregulation and inability to forge healthy relationships.

A challenging consequence of intergenerational trauma is the individual not being able to recognise it themselves; this is because the transferred psychological and behavioural patterns are normalised within families. The inability to communicate in relationships and poor coping mechanisms may become normal.

The importance of acknowledging and decoding Dalit trauma is paramount. The issue of caste is complex; understanding this aspect of caste allows us get a deeper insight into what it means to be Dalit. The mental health of marginalised communities, be it the LGBTQIA+ community, the Adivasis or Dalits has an additional layer of societal stigmatization and oppression to deconstruct, and in order to level the grounds for everyone, we need to comprehend the unique experiences these communities go through.

Also read: Dalit Women Will Get Justice Only If Casteist Judicial System Is Uprooted

If a Dalit individual decides to avail therapy, it is essential that the therapist understands Dalit trauma, even if and especially, in case they belong to an upper caste. We need to address the scathing issues that slap us in the face every day, the crimes and atrocities against Dalits and the systemic treatment of them, but we also need to engage in conversations that are not just limited to visible damage caused by caste apartheid. We need to understand caste privilege and call out even the subtler forms of discrimination, within our social circles. We need more inter-caste marriages and relationships. We need exposure to Dalit literature, art, and history.

‘The broken people’ are not supposed to be broken anymore, the responsibility lies in the hands of everyone – Dalits and more importantly, non-Dalits, especially those who are in the position to educate themselves and further the narrative so that we can begin to dream of an anti-caste India.

Additional Reading

‘An Exploration Of Four Dalit Narratives As Trauma Literature’ by Upaasana Suresh

Featured Image Source: Upliftconnect.com

About the author(s)

Priyanka is an unfulfilled engineer and an MBA graduate from IIM Indore. She is a writer, interested in carving the world through her biased lens, painting pictures with heavy imagery and highlighting the mundane, often ignored, but essential aspects of life. Her latest project is The Mental Indian, an attempt to de-stigmatize mental health in India, through stories, perspectives and conversations.

Beautiful article… Need of the hour…!

scholarly. how ever, please do take time to watch this lecture, that refers to ‘post-traumatic slave syndrome’, to appreciate the implication of focussing on the victim. https://vimeo.com/99562339

sushrut