Historically, statues in public spaces have been used as means to strengthen social and political hierarchies. They have been constructed to colour certain acts god-like, and grant select personalities morally and socially superior connotations. If one wants to draw conclusions about the fabric of a society, a look at the nature of the public spaces suffices.

Societal and historical precedent link the concept of visibility and privilege – all that is visible is acceptable. Visibility ties itself to multiple acts of privilege, such as the opportunity to interact and debate, to think and talk, and to hear and be heard. Minorities continue to be deprived of such avenues of development, and this repressive cycle reinforces the suppression of those made to limit themselves to the background and backstage. To date, one can easily see how the loss of public spaces manifests itself. Policies have a blind spot with regards to minority needs, and the bridge between public provisions and their actual issues lacks legitimate recognition. The Indian government’s blind spot to contraceptive and sanitary product needs during most of the COVID lockdown hassle testifies to this.

A UN report, dated early May, revealed that about 19.1 million babies will be born in India as a direct result of the COVID-induced lockdown. About six months post the careless setback; women are still waiting for tangible family planning provisions.

The secondary status granted to minorities is further strengthened by the lack of minority voices in public spaces. We continue to be fortified and aligned with centuries-old, rusted but revered ideals that we prioritise over providing safety to communities that need it most (the LGBTQI+ community is one that comes to mind). Not only does this hinder them from accessing and shaping public spaces, but also merits them to wage a war – both internal and external – in order to be accepted by society and state. We do this often by choosing to embrace a dismissive and heroism-laced history in the name of heritage. The implications of this are many, but all of them can be linked to the prime sorrow of all societies – all progress and development is mechanised and adjudged on a tarnished collective self-identity that is unwelcoming, invisibilising and often, dehumanising.

A visual declaration, like monuments or statues in public spaces, is universally interpretable, easily acceptable and oft-impository. It is more concrete than the written word – it invites no questions, welcomes no thoughts, and sets the narrative in stone, quite literally. Of late, however, the essence of a lot of monuments and statues in public spaces have been revisited.

Such narratives often draw strength from visual aid rather than the written word. A visual declaration, like monuments or statues in public spaces, is universally interpretable, easily acceptable and oft-impository. It is more concrete than the written word – it invites no questions, welcomes no thoughts, and sets the narrative in stone, quite literally. Of late, however, the essence of a lot of monuments and statues in public spaces have been revisited.

Also read: Is The Slew Of Giant Statue Announcements One Big Pissing Contest?

Most recently, the Black Lives Matter protests for George Floyd that coloured America, saw protestors publicly taking down statues at public spaces. With the spread of the movement, people began denouncing not just Confederate memorials, but also those of racists, colonialists and slave traders. More specifically, statues of Christopher Columbus, Cecil Rhodes, King Leopold II and the likes became an object of public scrutiny.

Around the same time, the ‘Rhodes Must Fall’, a movement to take down commemorations of Cecil Rhodes initially at the University of Cape Town, also took Oxford University with more vigour than ever before. In fact, around a couple of years back, the University of Ghana took down Mahatma Gandhi’s statue on grounds of racism allegations registered against him. The argument remained the same – why should public spaces such as an educational institution (in this case), glorify someone who is cause for the repression of its very people?

These tools were exploited to command space as well as shape and police public discourse. The Nazi regime relied heavily on visibility in public spaces to further the propaganda that stood to their benefit – ideals of masculinity, leadership and heroism. Much on the same lines, the Soviet Union sanctioned large-scale construction of Lenin and Stalin statues in public spaces to establish the state as irrefutable. Further, the British Empire sanctioned statues of British monarchs and generals across their colonies to command superiority in face of the people they ruled.

Also read: Mayawati: An Icon Of Bahujan Struggle

Closer home in India, statues have been used as active political rebuttals and statements of power through decades. The Statue of Unity echoed across the country as a massive assertion of Indian and Gujarati voice, not only nationally, but also globally. The state of Uttar Pradesh has made its way to notorious fame planked on the same. Even the upcoming elections involve a strong contestation over the tall claims (quite literally) of the construction of a statue of lord Parshuram.

The discourse of statues in public spaces has shaped up to be a separate game of politics. Both the BSP and SP have previously gained traction because of their longlist of sanctioned works, especially in the state capital, Lucknow. However, even in that space, one can easily identify the difference between a minority leader Mayawati and the more socially ‘respectable’ SP supremos, in that the former has always had a negative connotation of engagement with ‘fickle’ politics for her seeming infatuation with statues.

While political documentation of the voices of the majority and the mighty has run its course through decades, in some instances, like Nazi Germany, said statues were done away with immediately from public spaces after the fall of the regime. This is telling, in that humans and societies do not stagnate. Unlearning and relearning is not a static process, and the account of human history must constantly be reevaluated to check for muzzled voices.

It is noteworthy, however, that despite all the evolution, the struggle for minority rights is one that is still in play. Most societies across the world have failed to act as an equaliser so far. Why then, must these individuals, some of whom were strong propellants of factors that pushed people into the margins, be able to command privileges that are far above what the minorities can avail?

Against the conservationist counterargument of the importance of lessons from history, it becomes important to draw the binary between history lessons and choice commemoration; statues in public spaces do not form history, for they are reflective of a choice of what we model, and what is our heritage. Similarly, some believe that simply removing statues from public spaces is equivalent to shrugging shoulders to an oppressive past.

Statues in public spaces do not form history, for they are reflective of a choice of what we model, and what is our heritage. Similarly, some believe that simply removing statues from public spaces is equivalent to shrugging shoulders to an oppressive past.

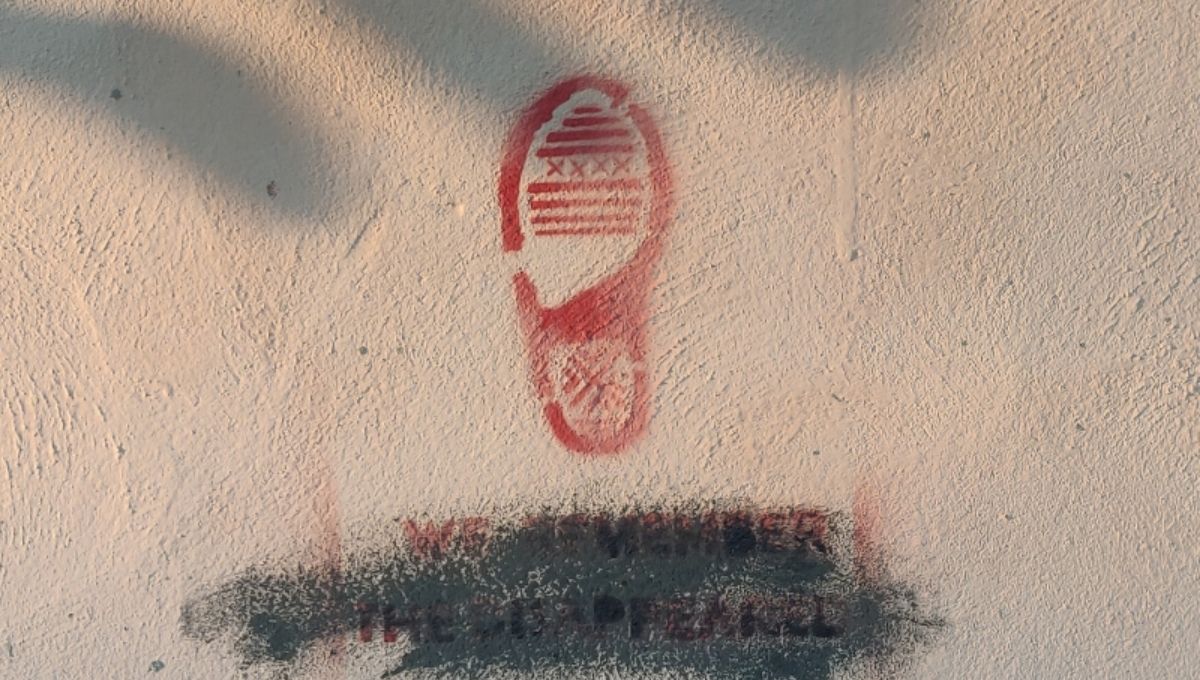

The aim, however, of iconoclasm is not to overwrite or dismiss events as they happened. The sentiment and impact of the act is to publicly dissent via withdrawing such narratives and personalities, being cognizant of the shortcomings of our institutions and refusing to continue aligning by those. One of the strongest images of popular liberation so far is the image of people beating Saddam Hussein’s statue with shoes post taking it down upon the US invasion of Baghdad.

Against all conflicts that emerge out of the politics of statues, some people look up to these people in context of their contributions and achievements. It is imperative we recognise these people do so out of a combination of privilege and detachment. For one to be able to shrug to a Rhodes statue, one must be able to establish colonies and colonialism as abstract concepts that did not define the trajectory of their communities over the span of several generations.

It thus becomes important to not only prioritise the empowerment of minority and powerless voices, but to also substantiate the same through actions, such as rescinding all narratives that propagate the oppression and prolong the fight for equal acceptance. Progress is saturated when these hierarchies are left unchallenged and discourse unengaged. To us our histories are built of bricks – laid by (and often for) those who had nourishment for strong arms, the avenue to bare them, the opportunity to flex and the audience to gasp. When we set these people of privilege in stone, we consent to conserving an unyielding context built by and for them, and we hinder all potential progress from manifesting visibly. Because even if you think you nod to both, what do you finally have set in stone?

Sangavi is a left-handed Math major at Jesus and Mary College and a One Future Collective Fellow of 2020. She is passionate about all things numbers, debating and policy. When not trying to strike a balance between the three, she can either be found reading or complaining about not getting to read enough. She can be found at Instagram or LinkedIn.