Over the past decades, Gender studies in India, has acknowledged caste as a key variable in understanding ‘gendered relations’. However, the gender relations specific to non-Brahmin, upper caste frameworks such as the Bania and Kshatriya communities, for instance, remain understudied and underreported. Caste-Gender intersectionality has tended to centre the umbrella framework of ‘Brahminical Patriarchy’ as an oppressive force. While Brahminism supplies the ideological skeleton and blueprint which determines the gender roles within family and society, some notable ‘varna-specific anthropological customisations’ also exist among the Kshatriyas and Banias.

Furthermore, in opposition to ‘Brahminical Patriarchy’, the discourse has gravitated towards ‘Dalit Feminism’. Unfortunately, the ‘academic gaze’ upon Dalit Feminism continues to be predominantly upper-caste, that is to say, there are way too many Dwij-Savarna women writing about Dalit feminism. This creates an issue of positionality and therefore it is not surprising that many Dalit and Bahujan intellectuals have repeatedly pushed back against this cultural appropriation.

One way in which upper-caste feminists can contribute significantly to the anti-caste intersectionality, without appropriating Bahujan discourse, is to focus on critical issues within their own varnas. Brahminism is no ally of women’s movements, and neither do Kshatriya or Bania cultural frameworks offer women’s emancipation beyond tokenisms.

There is hardly any meaningful literature in terms of how Bania women are co-opted into the caste frameworks of their own society, and how they live their lives ostensibly ‘free’ but under perpetual dependence upon the men of the household. In most Bania households, the women have deeply internalised a subordinate position in domestic affairs. Yet, there is no great feminist upsurge against this. There is no organised outward resistance either. To better understand this paradox, we need to take a closer, critical look at the anthropology of social relations within Bania households.

In most Bania households, the women have deeply internalised a subordinate position in domestic affairs. Yet, there is no great feminist upsurge against this. There is no organised outward resistance either. To better understand this paradox, we need to take a closer, critical look at the anthropology of social relations within Bania households.

Also read: Bahu-Aagman: Of Woman & Familial Harmony In A Marwadi Rasam

Contours of a uniquely oppressive anthropology

Historically, the Bania community’s pride and purpose rests in trade. Bania empires are not created by the sword but by the ledger-book. The women have a different role in Bania society. In a community of traders, business alliances are often built upon favorable marital matchmaking. In endless business cycles, to ensure the continuous circulation of capital and credit within Bania communities, fiscal sureties are needed. Within this framework, a marital connection with the creditor is as good a banking guarantee as is property or any other liquid or immovable asset.

While this may appear harsh but in truth, most Bania women know instinctively that they have a role to play in the expansion of family commercial interests by bringing ‘families closer’. Meaning no offence, but wording this non-sentimentally simply means that within Bania society, women represent tradable commodities who can, and have, been used for centuries to cement business ties through kinship. Many young Bania women express helplessness over this situation but often confess “there is no other option”.

This perceived lack of options, the ultimate resignation, is a result of a specific anthropology of Bania society which grooms girls from a young age to fit into this framework.

A key feature of this anthropology rests on standardisation of family life. This is very evident in a cursory survey of any urban, upper class Bania household irrespective of where they live. It is common to find Bania families not adopting local language or culture despite existing in that geography for generations. For example, Bania family who has been living in Madurai for three generations will be strikingly similar to a Bania family residing in Punjab, or Calcutta, or Guwahati, or even Boston. Most such families will not speak in Tamil, or Bangla or Assamese within their homes, where Marwari or Gujarati will still prevail. The interior iconography, arts, food, rituals, etc., all appear unaffected by local traditions despite decades of living in alien geographies.

Inside this ‘standardised bubble’, the Bania cultural continuity stays protected. This is true for both Hindu and Jain families, wherein despite their religious differences, the caste-cultural fabric is very consistent and contiguous.

Even in the 21st century with its digital disruptions, the Bania ‘standardised bubble’ has been quick to adapt. New ways are constantly created by the elders to explain “modernity” to the younger Bania generation in a way that their traditional values are still retained. This level of grooming creates a strange silence, a near totalitarian control over the criticality of Bania women. It breeds a culture of resignation and ignorance, with legitimacy only for the most superficial and token feminist praxis. It is therefore not a contradiction to see young Bania women posing in T-shirts with feminist slogans while sharing the same excitement to participate in marital pageantry of an ‘arranged match’ of cousin whose family rejected her relationship with a ‘non-compatible’ boy.

Like any effective system of ‘grooming’, the Bania society too has a very intricate reward and punishment system. There are ways in which Bania women are validated and made to feel important and even empowered, but it always comes with a catch. Any deviation is met with a staggered and ever-escalating reprisal. These start from family blackmail, to excommunication and isolation, to ultimately violence. Pressure is not just applied on the individual ‘erring woman’ but also on her immediate family by the larger Bania social collective. Thus, through these coercions, the woman or the whole family, can be brought back to the fold.

Furthermore, there is also an omnipresent religious footprint in daily family life as a sophisticated network of religious organisations, jati-biradri institutions, community NGOs, re-education centres, Jain-Bania schools, etc., which perniciously keep every Indian middle class Bania household, only one or two degrees removed from the local religious ashram or math. As a combination of all these above mentioned social structures, young Bania women grow up amidst heavy ‘grooming’ in a deeply surveilled and regulated social system.

This ‘grooming’ of a middle-class Bania woman continues to loop until the married Bania woman herself becomes an instrument of grooming, completing the cycle. Along with being confined in rigid ideas of gender, the indoctrination she goes through also teaches her the ways of perpetuating the same manipulation towards people of the lower castes, especially other women.

Necessity of Critical Ambedkarite analysis

Since the Bania family life is deeply oriented towards casteist prescriptions of gender roles, it is important to remember Dr. Ambedkar’s contributions on the emancipation of women, especially from the casteist social rules and regulations mandated for them.

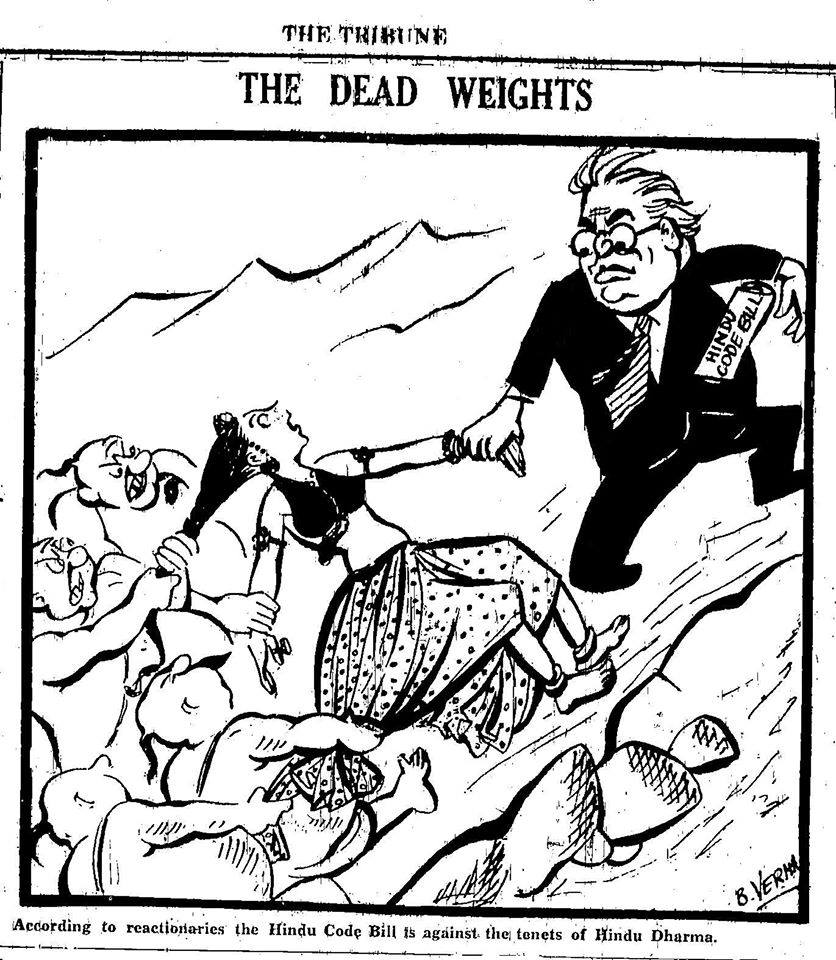

As the Chair of the constitution drafting committee of India, he made sure to enshrine Universal Adult Suffrage for all Indians, irrespective of their caste or gender (against notable opposition from upper caste men). Indian women thus won the right to vote which suffragettes had to fight for in the West for decades. Dr. Ambedkar had also been a supporter of equal pay for women, maternity leave with pay support as well as women’s access to birth control, raising these issues consistently from his early days in the Legislature during the 1920s. These measures were also resisted by upper caste male politicians of the era. His resignation as the ‘Law Minister’ from Nehru’s cabinet in parts was due to his frustration over the stalling on the ‘Hindu Code Bill’ which would have granted women equal inheritance rights and extended that to their children born outside of marriage a notion which was repulsive to the Brahminical administration.

In truth, gender was an important part of Dr. Ambedkar’s social and political agenda. In his earlier writings such as ‘Annihilation of Caste’ and ‘Castes in India’, he wrote about how the hegemony over women’s agency through social measures such as endogamy and the sexual ownership of women’s bodies perpetuates the hierarchy of castes in India. According to him, caste continues to exist due to the patriarchal dominance over women, and curtailing women’s freedom is a way of maintaining these caste hierarchies. Hence, he locates caste as an essential variable in the gender rights discourse in South Asia, and especially, India.

Borrowing from lived reality, social anthropological framework, when one compares the experiences of women in India, Bania women, being themselves complicit in perpetuating structures of casteist oppression, have a lot more privilege than Dalit-Bahujan women. However, their own lives remain heavily ‘groomed’ and dependent on the men within Bania households.

Borrowing from lived reality, social anthropological framework, when one compares the experiences of women in India, Bania women, being themselves complicit in perpetuating structures of casteist oppression, have a lot more privilege than Dalit-Bahujan women. However, their own lives remain heavily ‘groomed’ and dependent on the men within Bania households.

Also read: Not Jihad, It’s Love Actually

Thus, to hope for a Bania feminist consciousness, first the standardised bubble of Bania family life needs to be critically examined. And since the Bania ‘family-life’ is deeply rooted in caste structures, the ideal lens for examining this ‘bubble’ is therefore the critical anti-caste Ambedkarite perspective. Only via rigorous Ambedkarite anthropological analysis and painful de-Brahminising and de-Baniafication, can Bania women begin to see possibilities for truly emancipatory and radical feminist possibilities.

After centuries of being tradable commodities and banking capital in family-business empires, it is now time for Bania women to find independence beyond tokenisms.

Nioshi Shah is pursuing her Masters in Social Sciences at the University of Chicago where she is researching the anthropology of gender relations in Bania communities. She can be found on Instagram.

Ravikant Kisana teaches at FLAME University, Pune.

Featured Image Source: YouTube

What is so different in other “castes” and what they do to women within their own slightly unique social traditions in India? The article itself doesn’t outline any big radical differences between what a Baniya women goes through or what a Kshatriya women goes through other than the fact that those relations are “not yet studied in detail”. Even women in Brahmin households, how are they placed any differently? What is said here can easily apply to any caste in India w.r.t women. India is consistently and uniformly patriarchal across caste divide and even supported by other “higher more micro-powerful” women in their own subjugation.

There’s an odd strain of self victimising here. Savarna women aren’t “complicit” in oppression, they are oppressors, and any kind of oppression can be written off as “grooming” per this narrative. How is this any different from the way men are “groomed” in families and bro circles to enact violence?