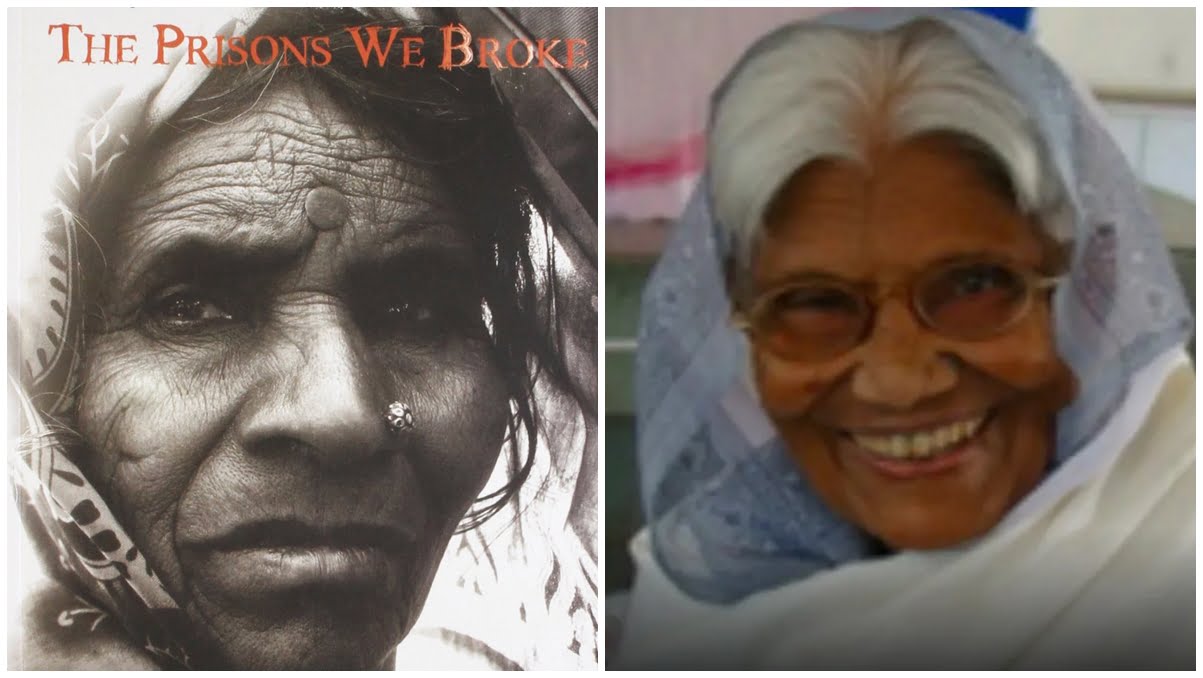

Babytai Kamble’s autobiographical work The Prisons We Broke was originally written in Marathi as Jina Amucha and was later translated into English by Maya Pandit. It can be segregated into two sections on the basis of the arguments she presents. Firstly, she pursues a broad thematic portrayal of the otherness of Dalit women within their own community. Secondly, she extols the role played by fellow women in following in the footsteps of Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar to dream of equality with upper-caste Hindus in the social order.

In The Prisons We Broke, Babytai Kamble uses her life as a source to identify Dalit oppression painting a raw imagery of the crude realities of their world. Growing up in a Maharwada in Maharashtra puts her in prime position to witness Dalit oppression at one of its worst, because Maharwadas are the epitome of the prejudices of the Hindu caste system which are most prevalent in and around Maharashtra. Maharwadas usually consist of close to 15 families belonging to the Mahar caste situated in the outskirts of villages of Maharashtra, which ironically owes its etymological origins to the Mahars who are the original inhabitants of these regions. Maharashtra being one of the states where the caste structure is most prevalent, The Prisons We Broke is justified in being a comment upon Dalit oppression.

Also read: Dalit Literature From The South: Countering The Savarna Saviour Complex

Maharashtra has witnessed Dalit rebellion in literature, war, religious practices inter alia over centuries. The Prisons We Broke is one such attempt, albeit one of the firsts by a Dalit woman justifying its narrative on women’s issues.

That is not to say that this dominance has not been met with backlash. In fact, Maharashtra has witnessed Dalit rebellion in literature, war, religious practices inter alia over centuries. The Prisons We Broke is one such attempt, albeit one of the firsts by a Dalit woman justifying its narrative on women’s issues. Scholars have categorized feminism in three broad waves in India, where the first two waves (extending from 1850 to just before independence) consist of characterisation of feminism solely by elite upper-class men with a saviour complex since political consciousness ran low in Indian women then as they were kept on a leash using familial and religious institutions. Even within the third wave feminism, there are three recognised sub-categories, namely (1) The Period of Accommodation, (2) The Period of Crisis and (3) The Period of Empowerment. During the ‘Period of Accommodation’ which can be said to have gave way to the ‘Period of Crisis’ somewhere around the 1960s, socio-economic issues were the major concern of the feminist movement in India.

Babytai Kamble, born 1929, wrote The Prisons We Broke (original Marathi: Jina Amucha) in 2009 and a majority of the book constitutes of her lived experiences that can be traced back to the years representing the ‘Period of Accommodation’ and onwards. Pinning The Prisons We Broke as literature from that period means the work should have focused on issues of women empowerment and gender equality. However, the theory of intersectional feminism explains how Dalit feminism cannot be said to be at par in its development and demands with the rest of the feminist movement in India and justify Babytai’s reliance on socio-economic disparities as the source of her writing in The Prisons We Broke.

Intersectional otherness of Dalit women

The central theme apparent in The Prisons We Broke is the intersectionality of the troubles of Dalit women. Babytai asserts in subtle ways throughout the book that if Dalits were seen as an othered community by upper caste Hindus, Dalit women were subject to the same treatment by men within their own community. This she ascribes to the established patriarchal social practices within the institution of family which make themselves most apparent only in the lowest social strata.

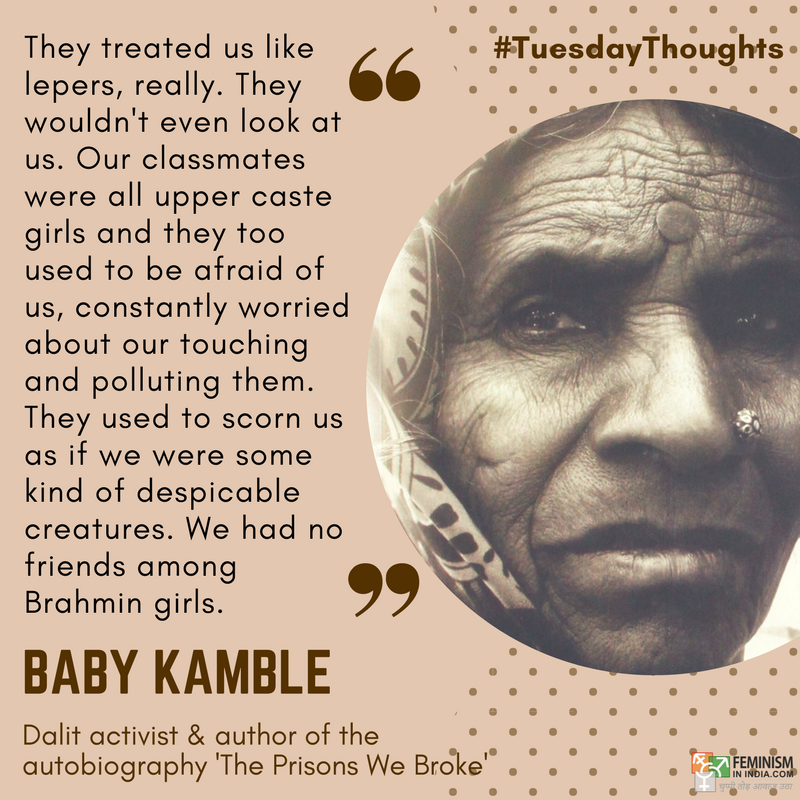

In fact, she goes on to point that power dynamics accruing on account of familial and sociological relations mean women are pitted against each other as well leading to worsening conditions for women in general. She cites specific examples of the relations between a woman and her mother-in-law and those between a Dalit woman and an upper-caste Brahmin woman to corroborate her argument in The Prisons We Broke. Babytai states it was commonly observed in Maharwadas that a woman would falsely accuse her daughter-in-law (aged around ten years at the time) of doing deeds she would not even comprehend, driving the young girl to death and coaxing her son into re-marrying a widow. She provides psychological reasons for this behaviour being one where the woman being incapable of projecting her pent-up emotions towards the society finds solace in her victory over an inferior being, even if it is at the cost of her life. It is this otherness of women which presents itself in intersectional forms that Babytai chooses as the subject of The Prisons We Broke.

Aversion to Hinduism and casteism

In The Prisons We Broke Babytai questions the superstitious practices of Hinduism followed and advocated by Mahars, despite being outcasts to the Hindu community evidenced by the fact that Mahars were required to live outside villages to not pollute areas inhabited by caste Hindus. Women had to face the brunt of superstitious Hindu rituals more than most on account of their lowly status in the Hindu society.

She supports this claim by examples firstly, of her own mother being reduced to such incapacity due to years of oppression that she could not maintain genial relations with any of her relatives and secondly, of women wed in the Maharwada who were required to keep a docile outlook donning their pallava and applying kumkum in the presence of men of their community. In a specific example, she provides context to this claim writing that for the wrongs of the women before Brahmins, it was the Mahars in general who had to face the Brahimn’s slurs immediately but it was the woman who would be rebuked and flogged later by the male of her household. She even suggests how mythological goddesses were considered inferior to the male gods of a superstitious Hindu religion.

In addition to the usual practices upheld in upper caste elite households such as women eating only after the men of the household have finished their meals, the Mahar women were subjected to discriminatory practices followed in the lower caste communities. For example, Dalit women having to bow down and step out of a road in the village whenever an upper caste man would approach. Later in The Prisons We Broke, she makes mentions of how Brahmin women would not touch them while accepting money, Dalit girls in schools were made to sit on the floor so as not to pollute the classroom for caste Hindus.

Babytai hits the nail on its head in retelling a tale of an odd practice where Mahar women had to carry the feces of newly-wed Brahmin women on their heads since Hindu custom required the Brahmin women not to leave the house even for the purposes of defecation during this period to ward off evils and because of the Hindu custom being averse to the idea of building toilets inside homes for the purposes of sanctity and purity of the household.

Walking the talk of Dr B. R. Ambedkar

Babytai sets the record straight at the start of The Prisons We Broke when she says she is addressing the millennials of her own community solely. In the second part of the book, Babytai recognises that the living conditions of Dalits have taken a turn for the better and that Dalits everywhere owe their betterment to Dr Bhim Rao Ambedkar. However, she believes that the magnitude of his contribution to the Dalit cause is not understood in its entirety by younger generations because of their newfound socio-economic rise. She also believes that the role of Dalit women in the uplift of Dalits should not be disregarded as well because they form as integral a part as any in spreading the gospel of Dr B. R. Ambedkar and paving the way towards a better future than lifelong shit-shovelling for their children.

In The Prisons We Broke, Babytai states that the Mahars were a superstitious people. Diseases of the body were typified as being possessions of the soul by gods and goddesses, further justifying a person’s death due to such disease as their entry into the metaphysical realm. This was because Mahars had neither finances nor access to medicines, but mostly because of a culture against education perpetrated by the upper castes to keep the Mahars from bearing the fruits of civilisation. Dr. B. R. Ambedkar changed such fundamental thinking of Mahars when he arrived in villages attired in a three-piece suit exhorting them to aim better material well-being and give up on the lifestyle designed for them by the Hindu caste system. Babytai remembers that Mahar women who were anything but rebellious up until that point in time would now go against the head male patriarch of the Maharwada in educating their children, adopting the practice of not eating dead animals and giving up superstitious rituals after the instruction of Dr B. R. Ambedkar.

Also read: Dalit Art: An Endeavour In Exploring Notions Of Caste Boundaries

The superstitious practices forced by the Hindu religious order upon the Mahars for eons have been referred to as prisons in the title of the book metaphorically, and Babytai claims that Mahar women were instrumental in rising up against these social evils designed to keep the Mahars in professions such as manual scavenging, skinning of dead animals and boot polishing amid other practices which corresponded to lowly remuneration to ensure their animal-like existence for generations.

These details validate her original argument of the cruciality of women in defying age-old customs and ultimately leading their people to prosperity, which was kept from them by the higher ups in the varna system. Also, especially this part of the book makes the title The Prisons We Broke clear in its entirety. The superstitious practices forced by the Hindu religious order upon the Mahars for eons have been referred to as prisons in the title of the book metaphorically, and Babytai claims that Mahar women were instrumental in rising up against these social evils designed to keep the Mahars in professions such as manual scavenging, skinning of dead animals and boot polishing amid other practices which corresponded to lowly remuneration to ensure their animal-like existence for generations.

Critique

Babytai credits Ambedkar for initiating an intellectual discourse in which the Mahar women partook vociferously. The objective of making these claims is to call upon the younger people to understand their roots and to propagate the philosophy of Ambedkar. However, as true and personal the accounts are, the writing lacks the inspiration and substance to stimulate any serious intellectual discourse as would have befit a work of this nature. To exemplify, there is no mention of critical writings of Ambedkar such as ‘The Annihilation of Caste’ to direct the young readers to understand the vision of Ambedkar. Since Babytai calls upon younger members of the Dalit community to recognise and appreciate Ambedkar’s role in their rise in the ranks through this work, it would have been more apt to pursue this objective in depth where the book only brushes upon it cursorily.

This could also be the very reason why this book has not received as much popularity among its targeted readers or otherwise, even if it has not gone unnoticed in history.

Satvik is a IIIrd-year student of National Law University, Delhi hailing from Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh. His research areas include law, casteism, religion, feminism, gender studies, sociology, Hinduism, politics, history and mythology. He has previously written research papers on feminism and casteism. He is also the founding member of the opinion website Critiqued focusing on issues of socio-legal significance. He can be found on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn.