It’s a strange thing, no? To be desired. In The Ways of Seeing, John Berger makes a distinction.

“…men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at.”

Toshada wants you to look, but she’s also doing the looking. A pout here, a hip jut there, the girl is all sass and spunk. With her gaze, Toshada challenges Berger, peering through the screen, challenging your notions of beauty and desire and confidence.

Also read: India And Its #MeToo Movement In 2020: Where Are We Now?

Toshada is also part of a larger story. You know the story.

Girl — Toshada, visual artist, model, and performer — says don’t touch me.

Boy — Iggy, owner of Cirrus in North Goa — does it anyway.

Girl calls out her discomfort in person.

Boy touches her again.

Girl calls out her discomfort on social media.

Boy claims he was being playful, proceeding to perform those very same acts on his mother to prove their triviality.

The community takes sides. Woman blames woman. Man blames woman. Woman blames herself.

An accusation of sexual misconduct can be broken into phases. The first phase is the alleged act. The second phase is the accusation. The third phase, the one we forget about, is the aftermath of the accusation. For many celebrities, the aftermath consists of a return to the spotlight. The return can be achieved through apology, denial, or silence.

This story is about the aftermath.

***

Callout culture depends on social media as a tool for ostracisation. There is a code embedded in misogyny. Women like Toshada, when they call out this misogyny, are attempting to shift this code. Shifting culture is akin to shifting continental plates — monumental, inter-generational, and very, very slow. Callouts create a culture of fear, particularly for those who call themselves feminists, because they are held to a higher standard; they get scrutinised more closely.

Callout culture depends on social media as a tool for ostracisation. There is a code embedded in misogyny. Women like Toshada, when they call out this misogyny, are attempting to shift this code.

Each step towards this shifting culture is painful. Which begs the question: what is the role of pain in enabling social change?

***

Toshada: I’m generally used to getting a lot of threats online, on digital platforms that I have amassed some numbers over the last few years. And I am in a very public space when it comes to my job as well. But when this narrative was pushed forth I saw a rise of anonymous accounts DMing me, saying I should come to Goa and they will show me what sexual harassment is. Others said you deserve to die for ruining the image of innocent men. You don’t know what rape is.

***

It is not easy to be a woman.

Our word is truth, and this truth is not fact, but memory. This truth exists in the spaces between what we know and what we’ve forgotten.

Truth #1: I was sexually abused as a child, so I recognise the damage that silence can do and the power that breaking that silence holds.

Truth #2: It is not brave to speak up, it is straight up terrifying, because the world will malign your choices and character and history.

Truth #3: The only one who gets to define my history is me.

Truth #4: I have never met Toshada; I’ve only texted her and spoken to her over the phone, It is familiar, her protection of her own body, even if there is always someone to invalidate us.

This story is about multiple truths.

***

Iggy posts his apology video on August 19, 2020. In it he states, Let’s close this chapter.

At the end of the video is another voice, that of the individual recording the video. The recorder’s name is Aerathe. He says, “There’s only so much you can explain. Sorry again, Toshada, if you were offended by me. I had nothing against you. I just had one point.”

Aerathe turns the camera so it faces him.

I’m not against Toshada. I’m not against rape. Like, I don’t vouch for rape. And my stance on rape is it should be punished with death penalty.

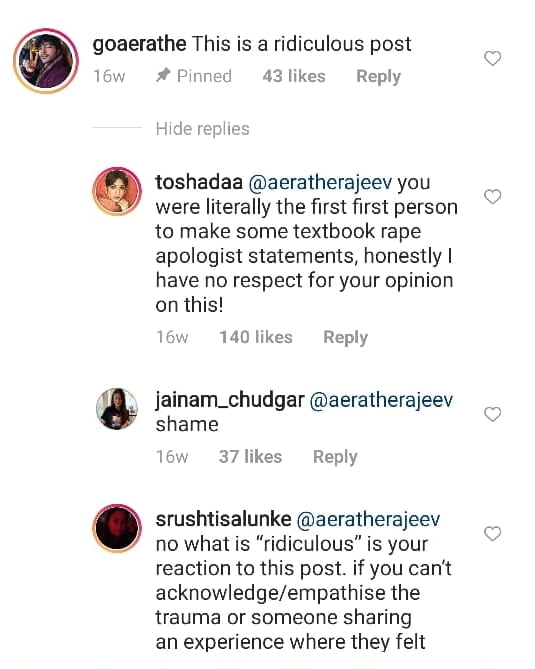

Two months later, Aerathe, one of Iggy’s closest associates, launches a full out smear campaign against the woman Iggy apologised to.

Every day, for the duration of this campaign, Aerathe sends Toshada a screenshot challenging her credibility.

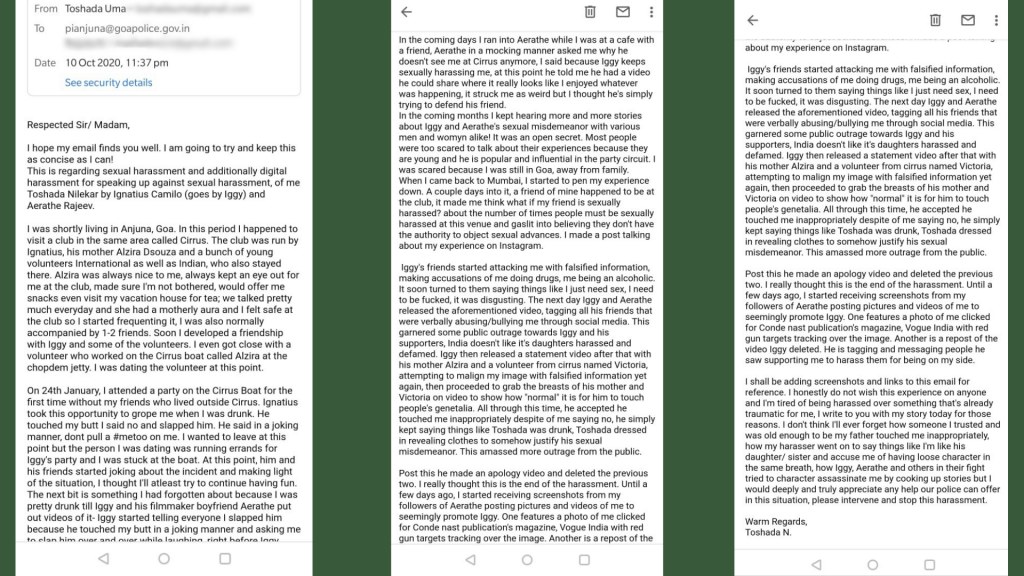

Toshada says: Aerathe took my pictures and edited them. He was deliberately harassing people who were supporting me. It’s straight up bullying. I took some legal advice from some people I know and I’ve written a letter last week to the Anjuna Police Station. The cops are deterring me from an official complaint because they say it’s not required. But if it continues, I might have to take a more serious legal route.

***

What is Aerathe’s truth? Why does he feel compelled to message Toshada after he’s apologised to her? And where do I, the transmitter of this story, fit in?

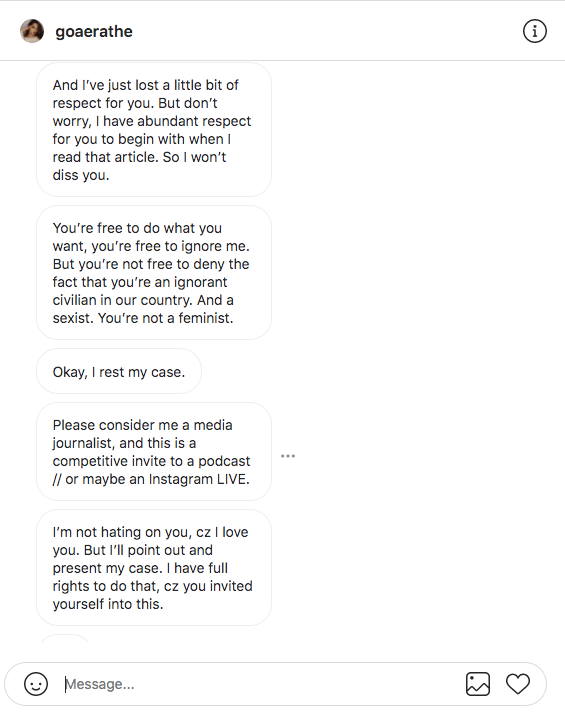

In October 2020, Aerathe directly messages me for the second time.

He says he respects me because I wrote a balanced piece. Then, the attacks begin.

I do believe that you’re ignorant. Cz I know more about what’s happening in our country than you do. Tell me your opinion on the Hathras case. Was that a rape I think it wasn’t a rape, let’s debate.

I don’t respond. He continues.

Cz by avoiding me, I’ll label you as ignorant, cz you’re ignoring the truth when I’m screaming out loud.

He invites me to do a podcast or Instagram Live, writes, “You’re free to do what you want, you’re free to ignore me. But you’re not free to deny the fact that you’re an ignorant civilian in our country. And a sexist. You’re not a feminist.”

It’s not easy to be a woman.

***

Richard Wrangham, a professor of Biological Anthropology, has studied pain. According to Wrangham, social isolation registers in the same parts of the brain connected to physical pain. Social alienation is as old as the existence of community itself. Pain, therefore, is a critical component of culture. “Everyone’s capable of being a victim, and everyone’s capable of being the executioner.”

***

This incident, the one involving Toshada and Iggy and now Aerathe, is fraught with more questions than answers.

What is the fate of the accuser? All they have is their word.

“Lose the power of the word,” says a character in the Netflix show Ozark, “and it’s like we lose ourselves.”

It is enough, sometimes, for the accuser’s word to anchor them, to be their Bible. But it is also a weapon, this word. It can break you, slice and sting like a wound steeped in salt water. That is what Aerathe, perhaps, is afraid of, and why he has, three months after the incident, created a new Instagram handle to troll Toshada with, because she blocked his old one.

Also read: “It’s Complicated”: Reflections On The Changing Ideals Of Romance Post #MeToo

If this is an example of Aerathe, as Iggy states, being affected mentally, then Aerathe needs help. If this is, as Toshada states, straight up bullying, Aerathe still needs help. But that does not excuse the harassment he is subjecting Toshada and her supporters to.

What is the fate of the accused? Are they allowed to move on? Have they learned their lesson, if there was one to be learned in the first place?

And what is to be said of the spectators, the ones who pull themselves into the debate? How should they respond? Do they need to take a side? Can that side change, and if so, how often?

Despite the muck, there are certain fundamentals that remain in place. Toshada said no. Iggy did it anyway. At the heart of it all, this is what matters.

Despite the muck, there are certain fundamentals that remain in place. Toshada said no. Iggy did it anyway. At the heart of it all, this is what matters.

The third phase of a sexual misconduct accusation, the one we forget about, is the aftermath of the accusation. In this case, the aftermath leaves Iggy unscathed.

Iggy says: “It was a small pothole in my life then. She is still trying hard to defame me.”

He says that Toshada’s fans — keyboard warriors, he calls them — send him hate messages. That is friend, Aerathe, got affected by this mentally. And Iggy? Well, I don’t even think about it.

In this case, the aftermath is a mess Toshada is left to navigate.

She says: “This person is playing his game. There are people supporting him through this. Every day I come across someone who supports his work and I have to cut these people out from my life. It’s not the perpetrator losing friends or opportunities. It’s me. It’s only coming down to me. The brunt is mine to bear.”

Remembering is for the past. This conflict — of truth and representation, of standing up for one’s beliefs, no matter the cost — is far from over. It will ruin us, our inability to listen.

Pragya is a spoken word poet, award-winning essayist, and author of two books. Her work examines the intersections between body image, mental health, and relationships. She can be found on Facebook as Pragya Bhagat and Pragya Writes and on Instagram.