Posted by Upasha Kumari and Dr. Tuli Bakshi

“One word frees us of all the weight and pain of life: That word is love.” — Sophocles

The idea of love is ubiquitous and eternal. We have been singing songs, telling stories of love since the birth of civilisations. Other mammals like dogs, cats or porcupines have no room for romantic love. They mate, sure, but as far as we’d know, do not develop romantic feelings for their partners. However, for us, the feelings of love are not only romantic, but allow us to create bonds that facilitate courtship and mating; leading to the perpetuation of the human species.

Evolutionary psychologists and anthropologists argue that love is a complex suite of adaptations and a mix of emotional and sexual desires designed to solve specific problems of survival. It promotes sex, conception and reproduction. Monogamy in humans yields greater reproductive output and survival of offspring, relative to other mating forms.

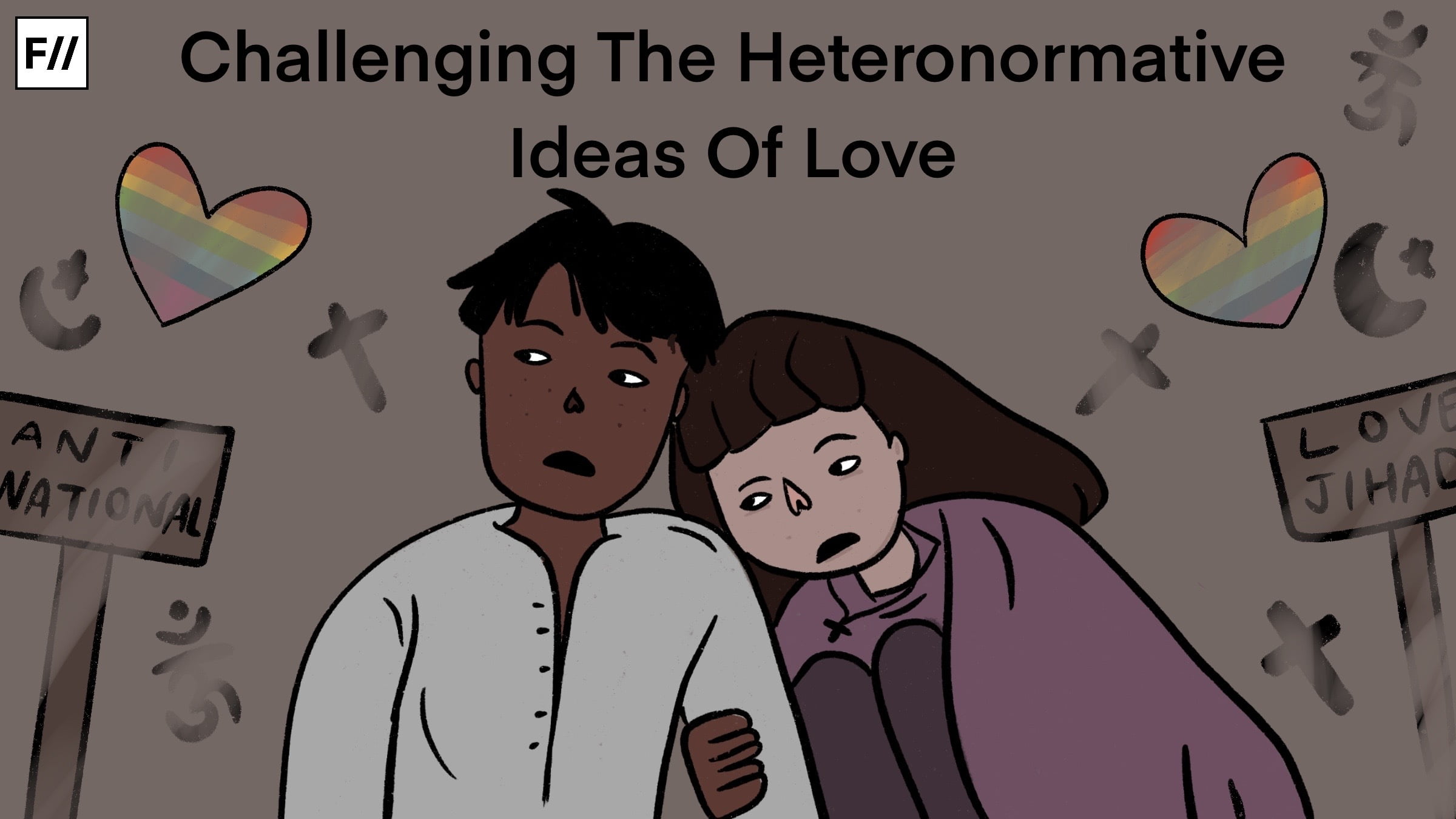

Of course, romantic love is not heteronormative; instead, it occurs irrespective of sexual orientation or gender. Although universal, scientists argue that love is a culturally coded phenomenon in the human mind and is learned through norms; hence the portrayal differs among various societies.

Even though American and Western cultures propagate the idea of getting married for love, historians suggest that this idea is modern. As seen even today, many Asian countries, especially India, promote the concept of arranged marriages where romantic love has little to do.

Also read: Revisiting Ennu Ninte Moideen In The Times Of ‘Love Jihad’

Even though American and Western cultures propagate the idea of getting married for love, historians suggest that this idea is modern. As seen even today, many Asian countries, especially India, promote the concept of arranged marriages where romantic love has little to do.

Historically, marriage alliances have always been seen as a mean to expand wealth, power, land and money, irrespective of class. Emperors used to have many wives that would help them with politics, business and wars. Although it may seem odd, but Vatsayana (the author of Kamasutra), a Hindu philosopher from 3rd century CE advised men and women to marry for love.

Marriages in India not only serve as a tool to exchange wealth through dowry rituals but also act as an institution to strengthen the caste system. In her piece “Caste kills more in India than coronavirus”, Sujatha Surepally, a professor of sociology and a women’s rights activist hailing from the caste-system based ‘untouchable community’, shows the grim reality of caste-related murders in India associated with inter-caste love affairs.

Portrayal of love has always been violent in the popular media and is a silent promoter of rape culture. Heterosexual desire is slowly learned through various discourses, with cinemas playing a vital role in teaching us how to be desirable subjects and objects. Famous feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey argues that the mainstream cinema has coded the erotic into the language of the dominant patriarchal order. Mainstream cinema has taught us that men should gain pleasure from looking and women are supposed to gain pleasure from being looked at.

The popular culture is obsessed with the heteronormative idea of love, which is defined by male power and control. Our movies construct the female sexuality as something that is not a result of her desire but a response to the pressure of losing their partner to another woman or conforming to some stereotype about the ideal woman.

Love-making is reduced to penetrative sex and the first-time experience of penetrative sex is wrongly portrayed as a comfortable and enjoyable experience for the woman. In reality, due to a lack of knowledge about the female body, most men actually do not know the role of foreplay in making the experience of penetration pleasurable for the woman. It puts enormous pressure on the woman to “perform” during the sexual act, such that their partner is satisfied with them. Thus, we end up behaving and reacting in the manner that the man wants us to act and feel, and such content ends up setting wrong precedents for the audience.

Novels and movies have been designing women to be virtuous and pure yet sensuous and sexy. The commercial films are notoriously sexist, misogynist and uphold the idea of stalking and harassment as a form of courtship and violence against women as a form of care.

Recent films like Arjun Reddy or Kabir Singh don’t just normalise anger, and violence, they sell dreadfully toxic and criminally negligent male behaviour as cool with abuse-and-love coming as a package. The problem is so pervasive that a man in Australia accused of stalking and harassing women told the court that he learnt this version of “wooing women” from Bollywood.

The portrayal of the LGBTQUIA* community in the movies is deeply problematic. Mostly gay men are shown in films with a feminine gait and always pining for the heterosexual male characters in the film to incite cheap laughter in the audience. Perhaps the film industry cannot digest the fact that LGBTQUIA* members have the same emotional, physical and sexual needs like any other human being.

Movies such as Ek Ladki Ko Dekha Toh Aisa Laga and the upcoming film Sheer Qorma make a humble start to rescue love from the narrow perceptions of hetronormativity by narrating the story of the female protagonist who is in love with another woman. Still most of such films focus on the heterosexual audience and how they react to non-heterosexual relationships. There is a long way to go before our films stop stereotyping love.

In India, the idea of love is also inextricably tied to the concept of weddings and associated rituals. Popular culture glorifies the Big Fat Indian weddings, along with the upper-caste traditions which uphold the patriarchal norms and values; one needs to interrogate these ideas from a feminist perspective.

Why is it that there exist markers of marriage such as the sindoor and the mangal sutra only for the woman and not the man? Verse 9.3. of Manusmriti, the Hindu Dharmashastra, reads that since women are incapable of living independently, they spend their childhood under the protection of their father, the husband guards her in her youth and the son in the old age.

Clearly, for the longest time, women have been considered the private property of the various male figures in their life. No wonder, there is a kanyadaan ritual in the Hindu weddings which is performed by the bride’s father. The girl is objectified, and she is reduced to a “gift”; the father gives her away as an “offering” to the groom who is considered to be a representation of Lord Vishnu during the wedding.

The co-author of this article, Dr Tuli Bakshi, defied this ritual in her wedding. She decided to have a simple havan for the sake of the family and chose to kiss her partner instead of participating in the ceremony involving the sindoor and the mangal sutra.

The concept of the big fat Indian weddings and the latest fad of destination weddings are undoubtedly a product of increasing consumerist culture, which considers the customer to be always right. Neoliberalism transforms people into subjects and disciplines them into consuming and behaving in specific ways which serve capitalist interests. Women’s freedom becomes restricted to choosing between consumer products. They are bereft of enjoying any real, meaningful freedom regarding how to live their life, the decision to choose one’s life partner etc. Thus, Indian brides become subjects to patriarchal notions amidst intensifying capitalist consumer culture.

Love, which is supposed to make us feel comfortable in our skin, instead becomes contingent upon looking attractive and sexy at all times such that we look appealing to our male counterparts. Our emotional needs of feeling loved become tied to how we are perceived on the outside, and the existing beauty industry exploits our insecurities.

Our idea of love suffers from internalised ableism; the social construction of disability in our society makes it appear that people with disability are not capable of giving and receiving love, or even engaging and enjoying sexual acts. Such an understanding is, of course, deeply flawed.

Our representations of love in the popular media whereby we expect a woman to be doting and dutifully performing household chores, maintaining the image of a “good wife” and a “good daughter-in-law” without any complaints, can be a source of significant trauma for the woman.

Also read: Arranged Marriages And The Quest Of A ‘Suitable’ Match

Our representations of love in the popular media whereby we expect a woman to be doting and dutifully performing household chores, maintaining the image of a “good wife” and a “good daughter-in-law” without any complaints, can be a source of significant trauma for the woman.

We sometimes wonder whether a feminist heterosexuality is possible because it is difficult to fight all the societal expectations from a woman arising within the patriarchal household while also engaging in a stable relationship with our heterosexual partners.

As responsible members of the present generation, we feel that there is a need to vehemently oppose the idea of confining love to the narrow categories of ableism, religion, caste, class, gender and sexuality. It is debatable whether the purpose of art is to reflect the behaviour and values of society or to push it to change for the better. However, it is certain that unless the popular media stops normalising violence, patriarchy and heteronormativity, love will continue to be the source of great pain and misery in life for many; when in reality love should be the most comforting, heartwarming and peaceful feeling we experience in our lives.

Upasha Kumari is currently a final year Master’s student at University of Delhi. She is a passionate feminist who engages with issues of gender, development and environment in her writings. She is fond of music, political philosophy and farming in no particular order.

About the author(s)

Dr. Tuli Bakshi, is a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Earth Sciences, IIT Bombay. She is also an LGBTQ rights activist and a blogger who writes on feminist issues.