Despite the end of the colonial era in India, the traditional hierarchies and the essential social order in the Hindu society with its multiple layers of graded inequality still remains untouched. The concept of ‘caste’ almost seems self-perpetuating, which roots itself in the economics of class, privatisation of property, and other structures of oppression, including Brahmanical patriarchy: debates and conversations that came up as we woke up to the rape and death of the young Dalit girl in Uttar Pradesh’s Hathras in September. On December 17, CBI filed a charge sheet against the four accused in the rape and death of the 19 year old girl.

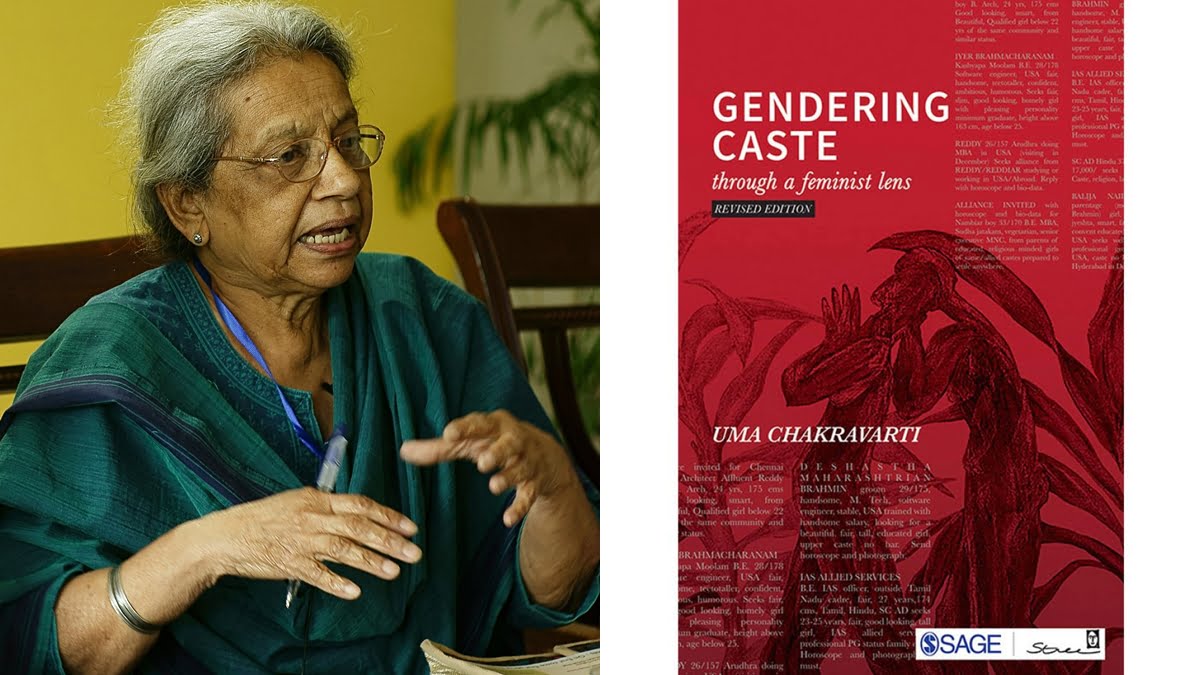

Uma Chakravarti, a feminist and a historian, in her book Gendering Caste: Through a Feminist Lens, argues that the systematic and structural oppression of women needs to be acknowledged in order to fully understand caste. A myriad of patriarchal practices within the larger framework of autonomy, kinship, labor, sexuality, access to material resources, and caste as a product of the consistent sustentation of endogamous marriages, have overtime moulded the relationship between gender and caste.

The prevalent rhetoric that views caste as a consensual system weaves the socio-political, economic and cultural domains of Indian society into one fabric needs to be discarded, since on the contrary, the rather oppressive ‘caste ideology denies the subjectivity to Dalits by depriving them of dignity and personhood’.

Also read: Towards A Dalit Feminist Standpoint – The Emancipatory Project For All Women

Owing to the social silence, oppression and inequality as a consequence of caste and patriarchy still remain eminent in the Indian society. Uma Chakravarti believes that the understanding of ‘caste’ should not be restricted only to the notion of purity and pollution, but it should be broadened to include other modes of oppression such as Brahminical supremacy, tyranny, and exploitation based on unequal access to material resources.

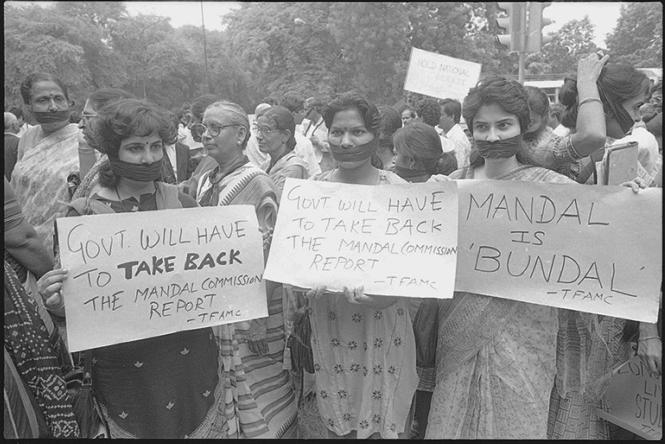

Uma Chakravarti builds on Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s work, and reiterates that class-based discrimination is universal, however, the perpetuation of endogamy has been crucial in the ‘unbroken reproduction of caste’, resulting in a form of inequality that is unique to India. She cites an incident at the anti-Mandal agitation where some upper-caste women protested on behalf of their ‘potential husband’ with placards that read: ‘We don’t want unemployed husbands!’

This inter-caste divide is so entrenched in the Indian society that the mere idea of marrying employed men who came from depressed castes seemed absurd to the protestors. Uma Chakravarti argues that this self-imposed unwritten law, that one should only marry within their caste, was what fuelled the continuance of the caste structures.

This inter-caste divide is so entrenched in the Indian society that the mere idea of marrying employed men who came from depressed castes seemed absurd to the protestors. Uma Chakravarti argues that this self-imposed unwritten law, that one should only marry within their caste, was what fuelled the continuance of the caste structures.

Such caste and gender divisions, subsumed within individual identities, echo the term coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw: intersectionality, which refers to the overlapping social and political identities resulting in multiple levels of oppression and social injustice. Crenshaw’s ‘trickle-down’ approach to social justice states that without the correct frames to see how all the sections of a group are affected, many fall through the cracks of a movement and are left to suffer in virtual isolation. Uma Chakravarti, on similar lines, argues that the identity of Indian women is not homogenous.

The Indian feminist movements are often criticized for failing to acknowledge, appreciate, and include the diverse struggles and multiple layers of oppression faced by Dalit women, which cannot be studied through a single theoretical framework. Historically the concept of purity did not burden the Dalit women since they worked as labourers in the public sphere. However, they were entrapped by triple-jeopardy due to their socio-political location in the society: a female labourer from the lower caste, and the operation of this three-fold oppression or Brahmanical patriarchy can only be understood by appreciating how gender and caste are structurally and inextricably linked.

According to a National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) report, the crime rate against Dalits has increased by 6 percent within a decade with over 3.91 lakh atrocities being reported, which mainly comprise of assaults on women to “outrage their modesty”. The fact that the social and political location of a Dalit woman makes her more vulnerable to sexual violence based on both caste and gender made it imperative that any sexual assault on Dalit women be covered under both Indian Rape Laws as well as the SC and ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act.

Catharine MacKinnon, in her paper Rape, Genocide and Women’s Human Rights, argues that rape is “a tool, a tactic, a policy, a plan, a strategy as well as practice”. Uma Chakravarti outlines some prominent abominable cases of sexual harassment in the Indian history where rape was used as a weapon in the hands of the socially dominant as an expression of violent rage to punish the ‘errant’ women as per Dharamshastras, to curb supposed deviant behaviours, and to reassert strategic control over the bodies, space, and resources of the already-marginalised Dalit women. MacKinnon would refer to this as “not rape out of control” but instead “rape under control”.

This review cannot be concluded without acknowledging and analysing Uma Chakravarti’s efficient and comprehensive engagement with caste and gender through this book, all of which seemed to be playing out in a tragic way in the Hathras incident.

This review cannot be concluded without acknowledging and analysing Uma Chakravarti’s efficient and comprehensive engagement with caste and gender through this book, all of which seemed to be playing out in a tragic way in the Hathras incident. Here, looking at the crime from the vantage point of the victim’s caste identity, a Dalit, is crucial. It unveils the uncomfortable reality of India as a casteist State where the lower caste communities are time and again terrorised through means of violence, rape, and murder to exert strategic control and power over them. More often than not, the legal and judicial system turn a blind eye to these atrocities, and worse yet, abet them.

Also read: Sangat’s Session On Faith & Feminism By Uma Chakravarti, Kamla Bhasin & Syeda Hameed

In the Hathras case, the victim was nationally gaslighted. From going against the age-old Hindu tradition of not cremating the mortal remains after sunset, the police set ablaze the victim’s body in the dead of the night to destroy any evidence along with the possibility of further scrutiny and denied the girl’s family their right to conduct the last rites, to producing post-mortem reports of questionable credibility that denied the occurrence of rape – all tactics seem to be employed to camouflage the fact that caste had everything to do with this grotesque incident.

This also has to be viewed in light of the fact that many “public intellectuals” commenting on this incident on mainstream media have constantly tried to underplay or dissipate the effect of caste in this and related instances. In all the appalling cases of sexual violence in the trajectory Indian history – Phoolan Devi, the Mathura Rape Case (1972), Bhanwari Devi (1992), Priyanka Bhotmange in Khairlanji (2006), Nirbhaya in Delhi (2012) being some of the most prominent cases – the Indian system has failed to appreciate the inhumane patterns of injustice and oppression that flow from the graded inequality that the rigid caste system breeds. Sidelining Hathras victim’s Dalit identity would mean the erasure of an extremely probable motive, and turning a blind eye to the gravity of control that the archaic Brahmanical patriarchy holds over Indian society.

The non-Dalit feminists and allies should, without appropriating their struggles, create space for Dalit women to demand accountability, redressal, and social change, rather than simply assuming narratives for the marginalised from an external standpoint.

Her eyes two dry hollows bear silent witness

To hundreds of deaths of her mothers, daughters, sisters

Their dreams, respect and their bodies.

Her calloused hands, her unkempt hair

Her cracked heels, her wrinkled hair

Tell the tales of living through fears and years

Of centuries and millennia of violations and deaths.

She was told

That she was dirt,

She was filth and

In this sacred land of thousands of goddesses

She is called a Dalit.

Asma Hussain is a final year law student at Jindal Global Law School, who never lets any opportunity to discuss books, poetry, or philosophy slip. She is a rebel with a cause, who strives to dismantle patriarchy and break toxic generational curses one day at a time. But first, coffee. She can be found on Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn