The terminology of upper and lower castes is used to indicate the assumed supremacy of some caste groups over others. As these elite groups do not acknowledge their privilege, the term “upper” and “lower” are used to represent their vision of the world.

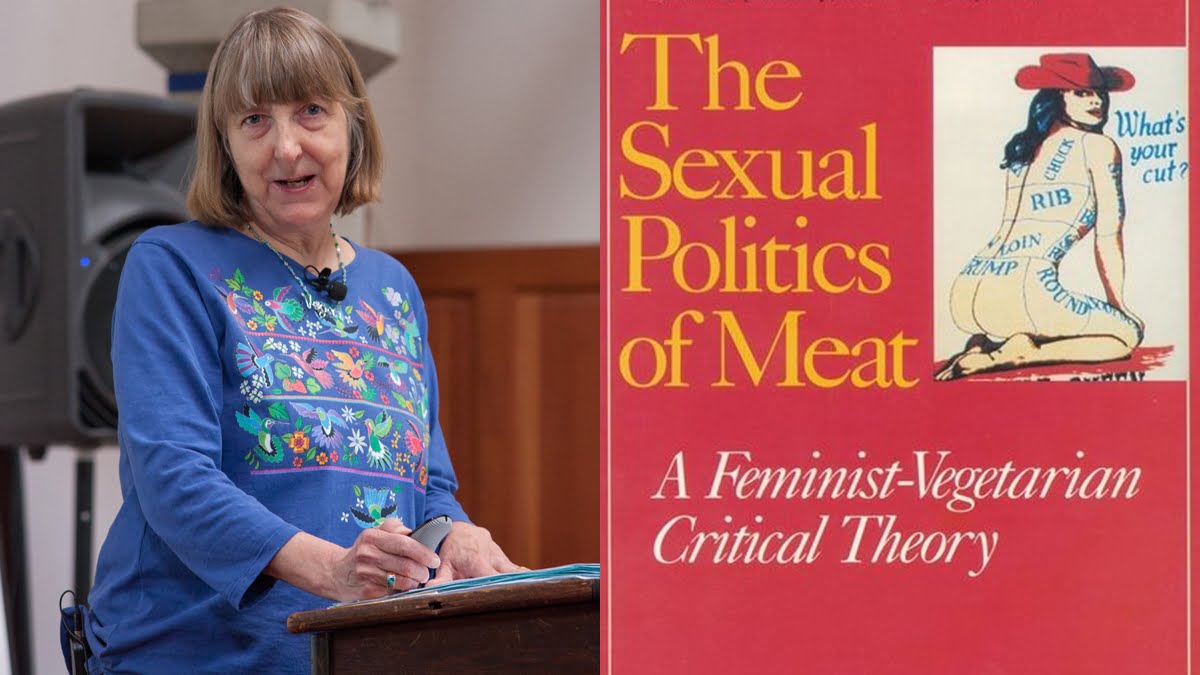

Let’s pretend that you are an Indian Hindu woman closely in touch with your roots and culture and hence, are intimately familiar with Brahminical patriarchy. You start to read Carol Adams’ 1990 book, The Sexual Politics of Meat. You won’t have to read far into it to come across statements that will strike you as outrageously inaccurate. On the very second page, you will encounter this:

People with power have always eaten meat.

Wait, this is not correct, right?

What is actually more accurate for you, in the South Asian context, is, that people with power do not eat meat. Clearly Carol Adams is not talking about your culture, where men with power are vegetarians. Caste-privileged people distinguish and elevate themselves on their vegetarianism and their near-divine purity, the fundamental tenet of Brahminical patriarchy, which is, however, just as insistent, harsh and tyrannical as the patriarchy of western cultures. It has the familiar pillars of western patriarchy: patrilineal succession, check; gender hierarchy, check; restriction of female sexuality, check. But Brahminical patriarchy is also infused with the Hindu caste structure, where an upper caste man’s social status is dependent upon imposing purity norms on women that oppress both women and the large tier of lower caste people.

Caste-privileged people distinguish and elevate themselves on their vegetarianism and their near-divine purity, the fundamental tenet of Brahminical patriarchy, which is, however, just as insistent, harsh and tyrannical as the patriarchy of western cultures.

Also read: What Has The Feminist Movement Got To Do With Food?

The thesis of Carol Adams’ first chapter is that “meat is masculinity,” where you will continue to see statements such as the following.

Meat is for brain workers.

Meat is a symbol of male dominance.

Meat is a symbol of patriarchy.

But in the Hindu customs, you know that Brahmins are the ones considered the “brain workers”. Brahmin males are those who entrusted themselves with the composition and learning of the scriptures, to preside over important ceremonies and to intercede between humans and the gods. It is the “lower castes” who are assigned various roles to maintain the day-to-day running of society, including security, commerce, the production of food and sanitation. It is not eating meat that is the symbol of male dominance, but the privilege of shunning meat, which is the food of the common people.

Vegetarianism is for Brahmin brain workers.

Meat is for “lower-caste” manual labourers.

Vegetarianism is a symbol of Brahminical male dominance.

Vegetarianism is a symbol of Brahminical patriarchy.

In Chapter 2 and elsewhere in the book, Carol Adams draws attention to the language used to describe women and their bodies – as “pieces of meat”. She connects the meat-eating culture to violence against women’s bodies. Ursula Hamdress, the pig shown in a suggestive pose, is a famous trope from this book. But that image is quite unfamiliar to you. Your head is full of song lyrics where women’s bodies are described as ripe fruits: perhaps tomatoes, but famously mangoes. Who can forget the line, “lady with breasts like mangoes” from the movie Passage to India, based on E.M. Forster’s classic novel? Despite the hegemony of vegetarianism, we know that India is a place of violence against women, and all forms of violence including rape threats are a common way to silence and control women. Even the reported rates of rape (88 a day in 2019) are underestimations, given the extreme stigma and victim-blaming that silences survivors.

In the later chapters, vegetarianism and feminism even become fused as one.

“Where does vegetarianism end and feminism begin, or feminism end and vegetarianism begin…Developing feminist-vegetarian theory includes recognizing this continuity. Our meals either embody or negate feminist principles by the food choices they enact.”

So, the implication is that if someone eats meat, they are not a feminist. That could be considered quite a stretch, especially in India where the opposite could be true: that by being a vegetarian the man adheres to Brahminical patriarchy!

The thesis of The Sexual Politics of Meat is that the oppression of women in patriarchy is linked to the oppression of animals, and the consumption of meat; that by freeing yourself from one, you can free yourself from the other; that feminists of the West in the last couple of centuries have been vegetarians or vegans, and that feminists should be vegans; finally, it also holds that vegetarianism and veganism challenge patriarchy. From the vantage of Brahminical patriarchy though, we can see that this thesis is blatantly misleading. Vegetarianism does not challenge patriarchy; on the contrary it is one of the very pillars of Brahminical patriarchy. Carol Adams is only focusing on the white, western patriarchy, and we know that patriarchal oppression of women can not just exist but can also be virulently oppressive when it is Brahminical. Brahminical vegetarianism disproves Carol Adams’ thesis as it stands. Patriarchal oppression can and does take many forms.

How did the elites of the subcontinent become vegetarian?

No doubt however, that it was Brahmin and other elite men who were responsible for the code of Brahminical patriarchy. Almost all the Sanskrit scriptures were written by Brahmins for other elites. They laid down the code for controlling women, lower caste people, as well as animals, to maintain not only patrilineal succession but also caste purity.

There is another way in which one might seek to salvage Carol Adams’ thesis. The West sees India predominantly as a victim of British colonisation where the peaceful vegetarianism of Gandhi is pitted against the powerful meat-eating white people, and to some extent this is also how Indians view themselves. Carol Adams quotes the European doctor George Beard who attributed British superiority to beef-eating. Whether or not this view was widely held by the British, it was definitely espoused by the subjugated Indians. As quoted and analysed by Parama Roy, a doggerel recalled by MK Gandhi from his own school yard attests to the self-perceived feebleness of the vegetarian Indian male.

Also read: The Eco-Gender Gap: Women Do More For The Planet Than Men

Behold the mighty Englishman

He rules the Indian small,

Because being a meat-eater

He is five cubits tall.

There is no denying the contradiction here: meat may be considered relevant to British domination, but vegetarianism is considered necessary for Hindu caste-based authority. Vegetarianism is a performative asceticism that also conveniently renders the elites unsuitable for manual labor. The subtext is that the upper castes are a people apart from the common majority, that they are inherently and innately refined in their intellect, their aesthetic sensibility and also, their moral character. It is acceptable for the laboring castes to eat meat, because they are not expected to engage in high-minded tasks. The most oppressed group, the Dalits, have been assigned the task of removing the dead bodies of domesticated animals from the thoroughfares. Being destitute, it has been the tradition of this community to scavenge the meat from dead cows.

So how did it happen that meat eating, which is the prerogative of all men in standard patriarchy, according to Carol Adams’ analysis, was eschewed by “upper caste” males? According to historical records, Brahmins did eat all kinds of animal flesh including beef but at a certain point in time, they relegated meat eating to the lower castes and took up vegetarianism. The clearest account of how this might have happened was presented by Dr. B. R. Ambedkar in his 1948 book, “The Untouchables”. This account has recently been vetted by authors George and George in the 2019 book, Beef, Brahmins and Broken Men. It is those two volumes I draw from in answering the question.

The earliest scriptures of Brahmanism, the religion that would develop into Hinduism, include descriptions of animal sacrifices. Such practices were not always a part of the civilisation in the Indus River Valley. Rather, they were introduced by Aryans, nomadic pastoralists who migrated into the subcontinent from the Eurasian Steppe in the second millennium BCE. They instituted a varna system that attested to the superiority of the Aryans over the native inhabitants of the area. Horses and cows, as well as other animals like goats, were killed in ritual sacrifices that were presided over by Aryan priests, who came to be known as Brahmins.

Because the cow was central to the pastoralist’s way of life, it was the main sacrificial animal. But in the agricultural society of the Indus River Valley, sacrificing a “useful” animal is necessarily expensive, and together with the inherent violence of sacrifices, there rose up a resistance to Brahminism. Buddhism and Jainism were part of the resistance, and these disciplines were preaching against both the needless slaughter as well as the assumed superiority, spiritual and otherwise, of the Brahmins.

The history of Hinduism is one of absorbing and mutating other prevailing spiritual practices into itself. In order to counter the Buddhist-Jain revolution, Brahminism adopted vegetarianism. Where it previously claimed the sacred cow by sacrifice, now it venerated cows by protecting them. Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd summarises Ambedkar’s theory:

“Brahmanism countered Buddhism’s democratic and egalitarian appeal by appropriating its message of ahimsa; the cow became the central figure in this appropriation. Whereas earlier cows were sacrificed because they were sacred, now the sacredness became an excuse for their protection. However, because there were people who lived outside the village, as Broken Men, and who had the duties of collecting cow carcasses and eating their meat, they became figures of scorn. Their degraded position, compounded by their poverty, forced them to consume leftover meat, resulting in the creation of a new form of discrimination: Untouchability.”

Thus meat-eating, and specifically beef-eating became a way to distinguish the elites from the oppressed and the down-trodden. It is not because of meat or muscularity that the Brahmin male has power; rather, the power comes from assigning an inferior status to women, and to men of other castes.

White supremacy is a brutal and variegated system but Brahminical supremacy is no less so. For the sake of the oppressed, be they human or non-human animals, we need to encourage a more comprehensive understanding of the forms that patriarchy can take.

What the West knows about Hindu vegetarianism has been controlled by the upper caste narrative, which couches it in terms of Gandhian ahimsa. The machinations of caste divisions are largely unappreciated even among intellectual circles there. Even when we have books on caste written by African American authors, the idea that one brown-skinned Hindu can so thoroughly discriminate against another brown-skinned Hindu is still hard for most Americans to grasp. White supremacy is a brutal and variegated system but Brahminical supremacy is no less so. For the sake of the oppressed, be they human or non-human animals, we need to encourage a more comprehensive understanding of the forms that patriarchy can take.

Rama Ganesan lived in Chennai until the age of 10, when she emigrated to the UK with her family. She then moved to the US in her twenties with her spouse. She received her BA from University of Oxford, a PhD from the University of Wales, and an MBA from the University of Arizona. She has two grown children, a dog and two cat companions. After reading “Eating Animals” by Jonathan Safran Foer, Rama began to explore the philosophy of animal rights and veganism. Over time this developed into an interest in the common roots of oppression of both humans and animals. She can be found on Instagram and Medium.