Posted by Khushi Agarwal

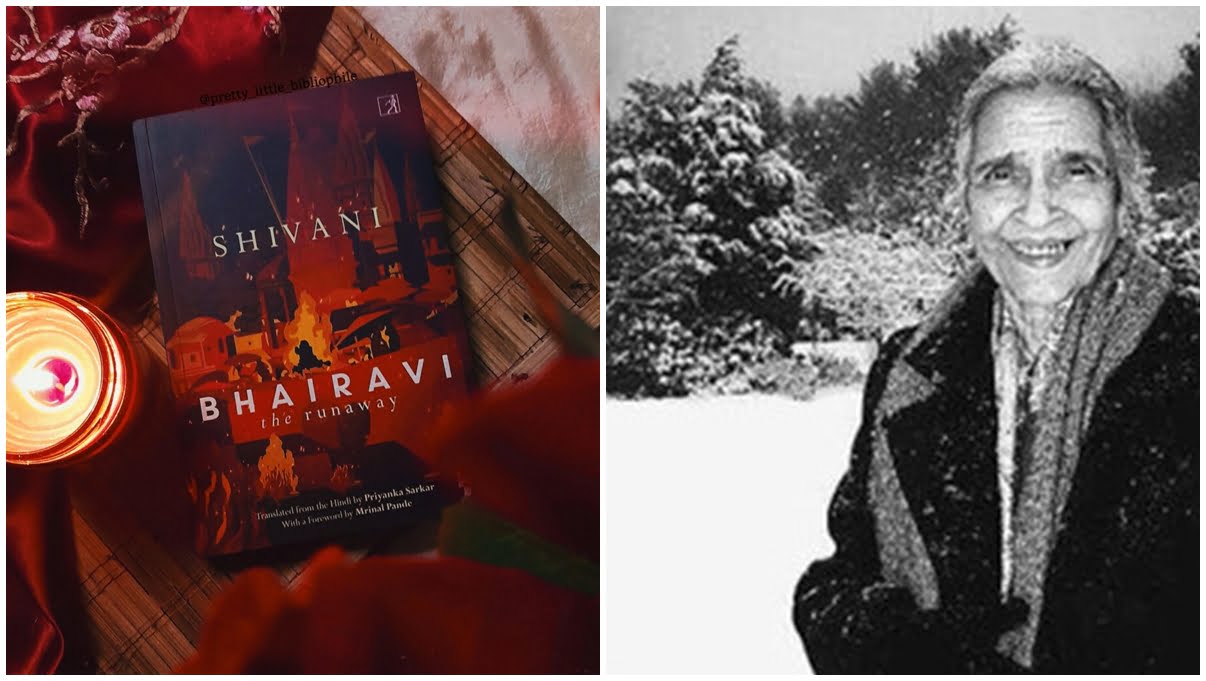

Chandan is the ideal woman in a patriarchy, with a name that exudes auspiciousness, an innocence that charms, and a beauty that captivates. For some mysterious reason, she jumps off a train and finds herself in the dark and dingy cave of the Aghoris. What is more is that she decides to stay among these Shaivite sadhus notorious for performing dark magic. What horrors in her past make her choose to live among these chillum smoking and meditating renouncers? Will this be the escape she desires? These are the mysteries unravelled in Bhairavi: The Runaway written by the Padma Shri award winner author Gaura Pant who goes by the nom de plume of Shivani.

Originally written in Hindi by Shivani and translated into English by Priyanka Sarkar, Bhairavi is rich in gothic imagery, employing the classic trope of western horror, a heroine stuck in a distinct land at the dwelling of an irresistibly handsome devil.

Originally written in Hindi by Shivani and translated into English by Priyanka Sarkar, Bhairavi is rich in gothic imagery, employing the classic trope of western horror, a heroine stuck in a distinct land at the dwelling of an irresistibly handsome devil. However, Shivani’s writing has a distinctly indigenous eeriness aroused by an enticing yet mystic Guru who keeps a pet snake around his neck and inspires the fixation of two women disciples. Mrinal Pande, infact, calls it the darkest of Shivani’s works in her foreword to the book.

Also read: Book Review | Migration, Trafficking And Gender Construction: Women In Transition

Chandan’s journey of self discovery in Bhairavi takes us into memories of her past, however much she tries to escape it. The plot of Bhairavi moves rapidly across time and setting: from Chandan’s childhood home which is partly a school, her mother’s house in the hills, her modern marital home to the trains of her travels. This fast pace, accompanied by powerful imagery, makes Bhairavi appealing to its new readers, decades after its first publication in the 1970s.

As we go on to learn about Chandan’s childhood and marriage, distinct voices of the women in her family come together, her experience being incomplete on its own. Her mother, Rajeshwari’s stringent demeanour and their somewhat isolated existence is contrasted with the carefree attitudes and vibrant lifestyle of Chandan’s in-laws. The shy and naive Chandan befriends her carefree and quick-witted sister-in-law, Sonia. What particularly resonates with the reader, is Rajeshwari’s struggle to raise Chandan alone as a widow and educate herself. The most poignant is her constant sense of repentance for what she sees as a youthful mistake responsible for all her suffering. Her fierce protection of Chandan in Bhairavi against a similar fate evokes both sympathy and admiration.

In fact, Shivani’s writing is known for its depiction of the challenges that women face, particularly those married against their will, showcasing their struggle for freedom and pursuit of empowerment, often through education. Therein lies the feminist leaning of her works such as Bhairavi.

The more we learn of Chandan’s past in Bhairavi, the more perplexing we find her present. The ashram becomes a site for Chandan’s transformation, where she acquires a rather carefree companion, Charan and a fearsome mentor, Maya didi. The graveyard of the dead, becomes the place for Chandan’s symbolic rebirth, as she is rechristened to be Bhairavi. Brought up by a Brahmin conservative mother, she has gone on to break caste and gender norms by associating with Aghoris and Chandals. The girl who struggled to leave the house under her mother’s watchful gaze, has now chosen not to return to her family, and instead start afresh amid strangers. The girl who was called a meek ‘lamb’, has walked across a graveyard without a second thought. The question that baffles us the most throughout is, will Bhairavi return to her family? Is it even her choice to return, or does a rendezvous with the Aghoris leave one unacceptable for genteel society?

The text dwells on certain ideas that might irk the feminist reader: fairness as beauty, beauty as virtue, the ‘disgraced’ modern women who smokes and wears western clothes, and finally, the virtuous Indian wife and daughter. Even though Bhairavi will not end your search for a liberated protagonist, it is a powerful depiction of how life is a lose-lose situation for many women. It is in many ways a story about how being the perfect wife and daughter is a precarious position, for Chandan as well as for her mother, one unfortunate incident can change everything. As if to say, women can keep trying but in an unfair society any sense of security can be short lived. Bhairavi disturbs the present-day notions about self belief, hard work and endurance which are woefully ignorant of power structures.

The end of Bhairavi leaves a lot untold, as Charan ventures into the unknown, Charan makes some hasty choices and Maya didi’s desires remain unfulfilled. These endings are all a product of the society these characters live in, the underlying social critique of their stories has not received the attention it deserves.

Also read: Book Review: Bhasha Singh’s Unseen—The Truth About India’s Manual Scavengers

Published by Yoda Press and Simon & Schuster India, Priyanka Sarkar’s translation attempts to stay as close to the original, retaining its nuances and linguistic style. I really appreciated this chance to get a taste of Shivani’s writing style. The end of Bhairavi leaves a lot untold, as Charan ventures into the unknown, Charan makes some hasty choices and Maya didi’s desires remain unfulfilled. These endings are all a product of the society these characters live in, the underlying social critique of their stories has not received the attention it deserves. Women’s writing(s), especially popular romance, is rarely seen as having any merit beyond entertainment. That is why today’s feminist reader may find value in reading Bhairavi and examining its perspectives. In any case, Bhairavi promises a multilayered story that arouses fear, temptation, curiosity and even poignance.

About the author(s)

Khushi Agarwal is an English Literature student from Miranda House and an enthusiastic volunteer for women and child development. Writing is her chosen mode of expression and activism.