Trigger Warning: Major spoilers, mentions of murder, rape, harassment

If you are a fan of Kalki Koechlin, only then you can survive the 8 episodes long Zee5 Prime series Bhram (meaning: delusion or hallucination), because there is nothing in the series that you haven’t seen already in Indian horror genre. The story’s protagonist is a famous writer, Alisha Khanna (Kalki Koechlin) who has recently recovered from a devastating accident that caused her miscarriage and husband’s death. While she suffers from PTSD, her sister, Ankita Paul (Bhoomika Chawla) and brother-in-law, Peter Paul (Sanjay Suri) invite her to their cottage in the hills for a change.

The series shows two timelines—year 1999 and 2019—with a few common characters. Both the timelines have a missing-murder case of a teenage girl who went out with her boyfriend in a small abandoned hut in the forest. The forest also comes with a folklore of a mysterious forest deity Okaala, who’s believed to punish those who do anything wrong in the forest. After her arrival in the cottage, Alisha starts seeing a dead girl Ayesha (Anjali Tatrari) who wants to tell her something—the typical plot.

What’s Wrong?

Complete erasure of mental health discourse

Alisha’s sister constantly pushes her to ‘move on’ in life, which is a bad advice for a patient with mental health issues. Both Ankita and Pradeep (Peter’s friend who’s interested in Alisha) intend to make her “settle down” with him.

It’s a common tactic of horror novels/movies where the mentally struggling protagonist (mostly woman) sees the “ghost” but is dismissed/mocked by people because—1) she’s a woman;so obviously no need to take her seriously, 2) they think she’s hallucinating.

It’s a common tactic of horror novels/movies where the mentally struggling protagonist (mostly woman) sees the “ghost” but is dismissed/mocked by people because—1) she’s a woman;so obviously no need to take her seriously, 2) they think she’s hallucinating.

Then in its climax they reveal that her experiences were never due to mental disorder but paranormal interference. Some of them also have a psychiatrist who’s somehow an expert in paranormal forces too (!) and makes her recall her memories under hypnosis which leads her to more information about the ‘ghost’. The same happens in Bhram too.

The creators of Bhram had every resource to learn about mental disorders, and yet, their highly privileged educated modern protagonist Alisha says, “Main paagal nahin hun (I’m not crazy)” to her sister once she ‘realises’ the existence of paranormal forces. This is very harmful in a country where mental health is a taboo even today. Since ages, mental disorders in women are seen as possession or are simply ignored and never treated, causing serious mental/physical consequences for themselves as well as people around them.

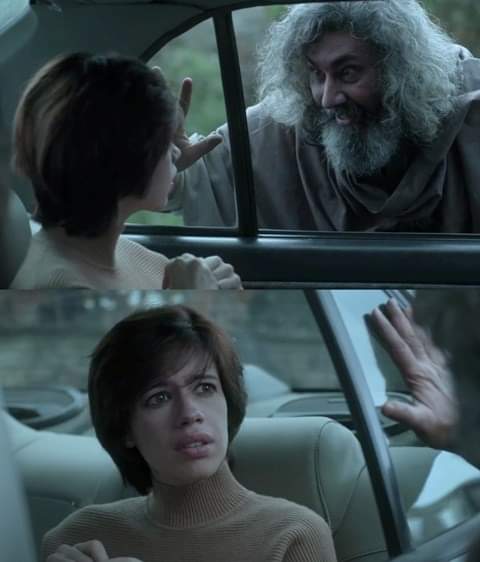

And the most annoying of them all, is the scene at the very beginning where a shabby-looking old man scares them with incoherent babblings about some premonition or supernatural powers. Why is it still a common practice to use old people with mental illness, weird hair, sometimes a physical disability and shabby clothes as a tool to scare/warn the protagonist/viewers?

Insensitive Handling of Religious and Cultural Identities

There are characters in Bhram from with different identities—among the group of five friends, Pradeep is Hindu, Peter and Alfie are Christian, Avtar belongs to a local tribe in the hills, Yakoob (and his girlfriend Ayesha too) is Muslim.

After Ayesha is brutally raped and murdered, Pradeep, along with Peter and Alfie, gives false testimony against Yakoob who then gets wrongly jailed (and tortured) for 20 years. Considering the statistics suggesting deeply rooted Islamophobia and bias among the Indian police, a much higher Muslim population among undertrial prisoners and the delay in their trials, the series shows complete blindness and apathy towards this reality while portraying the exact same narrative. Also, the objectification and fetishism of women from marginalised/minority communities is not new—Pradeep’s treatment of Ayesha and jealousy towards Yakoob suggests the same, but the series deals with it quite neutrally.

Avtaar is never called by his original name by his friends and classmates—they call him ‘Paglu‘ (crazy)—giving such kinds of names to tribal/marginalised sections is an outrageous, yet very common practice in India. His rich ‘friends’ always make him stand on guard outside their usual spot in the woods, instead of involving him in the conversation. Even in the present timeline, while all the others go on with their ‘successful’ careers, Avtaar is shown to work as Peter’s driver—maintaining status quo.

The Illogic ‘Okaala’

Okaala is the main climax of the story in Bhram. It’s not even surprising that the narrative around Okaala is portrayed in a manner that demonises and alienates tribals. Use of black wild horned creature’s mask for Okaala, long black hair with a black robed attire, hypnotic cinematography with scenes of Okaala performing some fire ritual—we’ve always seen it in the horror genre.

Okaala is the main climax of the story in Bhram.It’s not even surprising that the narrative around Okaala is portrayed in a manner that demonises and alienates tribals. Use of black wild horned creature’s mask for Okaala, long black hair with a black robed attire, hypnotic cinematography with scenes of Okaala performing some fire ritual—we’ve always seen it in the horror genre.

As per the series, despite Okaala being a deity, he may be imperfect; so when he wrongs, a new Okaala is supposed to arise in order to punish him (and we do see him in the end). The biggest joke is both the Okaala’s definition of ‘wrong’. In reality, there are plenty of wrong things happening in forests—illegal mining, forced deforestation for industries, smuggling, poaching, hunting for already endangered species—the list never ends, and tribal and forest activists are fighting against those for years.

However, the ‘wrong’ according to the first Okaala is teenagers having sex in that hut in the woods. It’s later realised that he is unfair and fake, so this invites punishment; but the 2nd Okaala gets activated only when the 1st one attempts to kill the main protagonist—basically the lives of all the others who were killed in the timespan of 20 years were worthless (!?)

Also read: Book Review: Feminism Redefined In Margo’s Memoir Called Negroland

Misogyny, Toxic masculinity, Bullying and Harassment Never Gets Solved

We see in flashbacks that Pradeep continuously objectifies and harasses Ayesha and never accepts her rejection. He’s extremely jealous of her boyfriend Yakoob and even suggests him to ‘share’ her with them someday (which results in a fight). His friends never call him out—Peter acts as a silent spectator and enabler, always stays by him and even does business in partnership with him.

Yakoob, despite being told by Ayesha that she feel unsafe around his friends, never seems to leave his toxic friends. Alfie succumbs to peer pressure and carelessly delays the meeting with his girlfriend Meera, which is directly responsible for her suicide. These aspects of the story are left incomplete, they’re never investigated or solved. They all constantly ignore, mock & boss around Paglu. None of them see anything wrong with this way of treating a friend.

Until the climax, viewers are very much convinced to punish the toxic characters and enablers whose deeds we see for the entire duration. But the climax is highly disappointing and disconnected from the entire series. After the final revelation, the whole burden of ill-doings is shifted on Okaala within a moment. Everyone else is acquitted of everything that was done before. This also indirectly reflects our society where people believe that ‘rape + brutal murder’ is the only worst way a woman can be harmed and no other combination of crimes against women can gain people’s attention, trust & response—a heavy indicator of rape culture.

We saw a similar narrative in Netflix’s Bulbbul where the Kaali maa-influenced witch gets activated only after Bulbbul is raped by a man other than her husband & not before that when her own husband brutally beat her damaging her legs.

There are also a few completely unnecessary and irrelevant sex scenes of the young inspector & his wife and lewd glimpses of her body just to entertain the (cis-het-male) viewers, in case they get bored with the cliched storyline.

Also read: Netflix Film Review | Paava Kadhaigal: A Heart-Wrenching, Hard-Hitting Anthology

My personal advice—watch it if and only if you want to see Kalki Koechlin, the scenic beauty of mountains and the woods together in a frame.

Featured Image Source: Zee5

About the author(s)

Mudita Sonawane studies Physics, Hindustani classical music and government policies. She has represented University of Mumbai in the 9th South Asian Universities Festival. She is an avid observer of politics and takes an interest in Photography and painting as well.