Every time an interview with a new fiction author lands in the newspaper, I drop everything to rip the sheet from the unfortunate owner’s hands and read it for myself.

What am I looking for?

Oh, the obligatory comments about how the author never believed their work would ever see the light of day, the long years of self-loathing as the errors to be edited multiplied like an infinite stairway, the periods of unemployment between soulless jobs when said writer tried to exorcise their literary demons and dissect them on paper. . .the staple parts of any author profile, really.

I want stories about the ten years of industry rejections and stabbing comments by pompous editors later forced to eat their own words. I yearn for heartrending descriptions of how the poor manuscript was exiled to the computer’s trash bin before its author had a last minute epiphany and rescued it for the final edit that secured them the publishing offer.

I don’t mean to romanticise the struggles of writers trying to break into a publishing industry known worldwide for elitism, discrimination, terrible judgment, and a phobia of risks. But that is exactly what made those interviews worth their weight in gold—they were stories of victory.

I simply aim to highlight the importance of social capital in Indian publishing. For example, valuable connections and closer proximity to industry gatekeepers than most and/or one’s employment in a profession closely related to publishing.

Yet of late, I have started to notice a change.

Where readers might have once learned about authors from a working-class or rural background, or about creators with no connection to the creative industries at all, they are now more likely to encounter reports about Indian fiction authors who worked in publishing companies, established themselves through journalism, or took time off for writing residencies.

The point of referencing such authors and their road to publication is not to question their merit. I simply aim to highlight the importance of social capital in Indian publishing. For example, valuable connections and closer proximity to industry gatekeepers than most and/or one’s employment in a profession closely related to publishing.

After all, who is more likely to be offered a generous book contract? The former editor/journalist who is known in professional circles, or the author from a marginalised class or caste or tribe without agent acquaintances, foreign degrees, MFA certificates, residency experience, online/offline platforms, or editorial experience?

Writers in the latter category cannot chat with future agents or bump into publishing executives at work. They must instead send their manuscripts to literary agents and publishers (only if they accept unsolicited entries) and then wait for a period of three to six months without an answer to know for sure that their work has been rejected.

Also read: On Penguin, Women In Publishing and Priyanka Chopra

After all, who is more likely to be offered a generous book contract? The former editor/journalist who is known in professional circles, or the author from a marginalised class or caste or tribe without agent acquaintances, foreign degrees, MFA certificates, residency experience, online/offline platforms, or editorial experience?

Creators and activists have been calling attention to the lack of diversity for years.

Where, then, do we look for working solutions?

While American publishing is no model to emulate, the conversations taking place there are essential to note.

After George Floyd’s murder in 2020, many American creators linked his killing by the police to the systemic racism that defines every aspect of life in America, including publishing and bookselling. In response, several literary agents took a decision to focus exclusively on the manuscripts sent in by Black authors and offered their time to help Black and Indigenous creators navigate the publishing process.

Activists and allies in the American publishing scene have also started far more nuanced conversations about representation and appropriation in literature. The #OwnVoices movement and #PublishingPaidMe are just two examples of this. Online pitching events such as #DVPit (DV stands for Diverse Voices) are held for marginalised creators alone, to reduce the distance between these authors and mainstream agents/publishers. Though institutional changes are needed, such basic actions are impossible to even imagine in Indian publishing.

Diversity in American publishing is also a travesty but there is better statistical proof of the problem. Racial equity is a talking point amongst booksellers and readers alike, which many hope will translate to representation, better stories, and agents/publishers who will champion diverse voices.

One such example was Angie Thomas’ best-selling young adult novel The Hate U Give (2017), which tells the story of a Black girl in a crime-stricken neighbourhood who sees her friend shot to death by a white police officer. She then finds strength in her family and community to grow from a traumatised murder witness into a bold activist. THUG released as a movie the very next year.

Also read: Press(ing) Business: Decoding Feminist Publishing In India

Would a marginalised debut author like Angie Thomas even stand a chance of being traditionally published in our own country? Here, privileged authors find fame after writing from the perspectives of fetishised tea sellers, car drivers, Dalits, and persecuted Muslims. Here, agents and publishers too often find best selling novelists in their friends, family members, and acquaintances.

The Indian publishing industry is folding into itself, losing more depth and dimension with each passing month.

Unless the very system is shaken up by the roots and axed open, I fear we will all decay under a barrage of mediocre award-winning novels about melancholy Brahmins trudging around their shadowy homes as they angst about their ruined relationships and changing societies.

Disclaimer: Angie Thomas has since moved on to work with a new literary agent and is no longer represented by the agent who worked with her on THUG. This article has been updated.

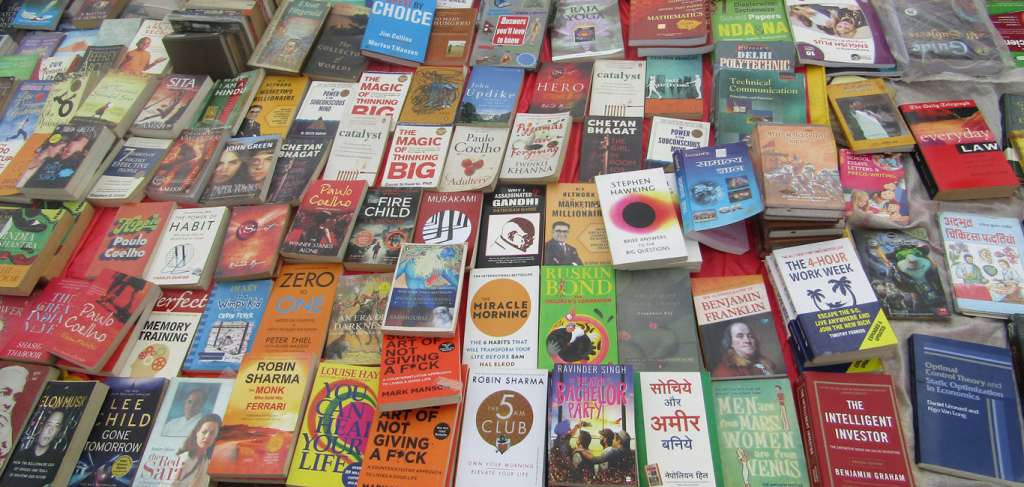

Featured Image Source: Outlook India

About the author(s)

Sahana is a journalism graduate and multimedia storyteller whose areas of study include digital media and society, publishing, healthcare communication, and postcolonialism. She spends her free time typing up novels, shooting 35mm film, growing her stamp collection, or eating all her snacks in a forest with no cell reception. You can find more of her projects on Twitter and Wordpress.