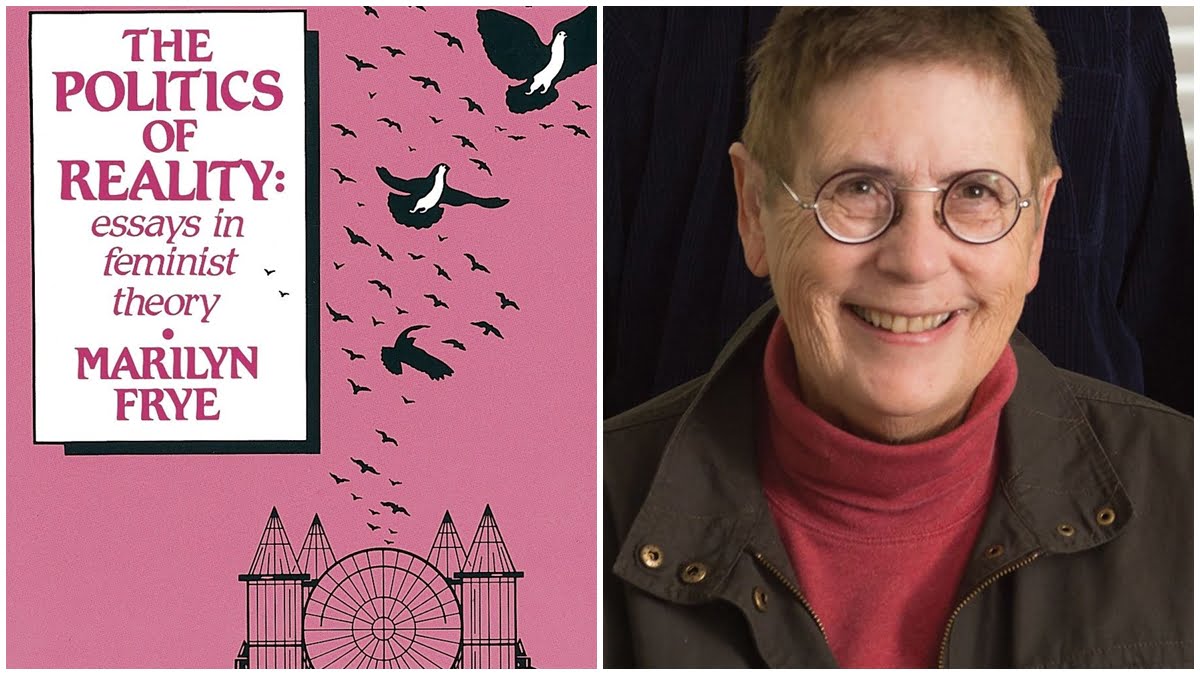

“Oppression is a system of interrelated barriers and forces which reduce, immobilize and mould people who belong to a certain group, and effect their subordination to another group (individually to individuals of the other group, and as a group, to that group).”

-Marilyn Frye

Marilyn Frye’s The Politics of Reality is a collection of feminist essays which were developed when Frye was working on on a course titled “Philosophical Aspects of Feminism”. Published in 1983, it has been hailed as a classic of Radical Feminist Theory. The opening essay on ‘Oppression’ goes back to its roots, in the word ‘press’, supplemented by the dilemma of ‘double bind’ for marginalised people – we cannot appear too happy or too rough; “Being happy makes us appear docile, and being rough makes us appear difficult to work with”. A peculiar aspect of Marilyn Frye’s work is the instances used to explore concepts effectively. She relates ‘double bind’ to expectations from women to be both ‘sexually active’ and ‘sexually inactive’, articulating the penalisation people oppressed by boundaries and forces experience.

A peculiar aspect of Marilyn Frye’s work is the instances used to explore concepts effectively. She relates ‘double bind’ to expectations from women to be both ‘sexually active’ and ‘sexually inactive’, articulating the penalisation people oppressed by boundaries and forces experience.

Also read: Book Review: Momspeak By Pooja Pande

‘Bird Cage’s View’ brings out the systematic nature of oppression, urging us to look at oppression through an intersectional lens. Myopically at one wire of a cage, we might feel that the bird can escape from that space. But moving back and looking macroscopically at how all the wires build up the cage, one understands why the bird cannot escape, it is trapped from everywhere. The inhabitants of the cage are often those who have been pushed into a relationship of responsibility and powerlessness, akin to women forced into domestic work. The act of opening doors for able-bodied women by men (the infamous ‘ladies first’) is on the assumption that women are incapable. If it were for respect, then men would also share domestic responsibilities. Marilyn Frye also discusses how men’s much-advertised inability to be emotionally vulnerable, and women’s restraint to be physically strong, are both part of the structure that’s oppressive to only women.

Marilyn Frye’s essay on ‘Sexism’ decodes the pervasiveness of ‘sex-marking behaviour’. During our interactions, there is a social pressure to identify the sex of the person and to let ours known. This is done through a variety of ways culminating into the ‘binary sex system’. The problem being that for men, this announcement leads to their safety; and for females, it leads to their victimisation and restriction, and invisibilising anyone who lies outside this spectrum. If we look at ‘sex’ and ‘gender’ as existing on a continuum, we would see everyone is performing drag, a performance. Marilyn Frye also creates a hypothetical situation about ‘pubic hair’ to discuss the moulding of behaviour as ‘conventional’ or ‘normative’, urging us to identify and resist how socialisation moulds ‘masculinity’ and ‘femininity’ as a biological trait.

Sexism, therefore, in a nutshell, is ‘sex-marking’ and ‘sex-announcing’ which divides us into dominators and subordinates. The essay ‘The problem that has no name’ deals with the problems of ‘Male Chauvinism’, ‘Male Supremacy’, ‘Misogyny’ and ‘Sexism’. Marilyn Frye articulates how women are denied their personhood and if they are perceived as a ‘person’, the ‘female’ identity is completely lost.

The next essays largely steer towards philosophical aspects of the feminist theory. ‘In and out of harm’s love: Arrogance and Love’ looks at mechanisms (like coercion, exploitation, oppression and enslavement) used in the exploitation of women. The author theorises how stripping off power and resources (which even the most socially powerless people have) can lead to a radical loss of self-esteem, self-respect and sense of agency. She then proceeds to decodes three figures comprehensively: ‘The Arrogant Eye’ – the world-view of a man riddled with arrogance, ‘The Loving Eye’ – the world-view feminists aspire, and ‘The Beloved’. In ‘A Note on Anger’, Marilyn Frye confabulates how women’s anger is perceived as being ‘upset’, ‘hysterical’ or ‘crazy’, even though women of the 19th century (suffragists, abolitionists, prohibitionists) extended the concept of rage for women, especially in public space.

Interestingly, anger is taken well on another’s behalf, making it is easier to be passionately ‘anti-abortion’ than be ‘pro-choice’. ‘Some Reflections on Separation and Power’ explores the parasitic relationship between the two sexes and the concept of feminist separation which offers control over access, allowing women to draw new boundaries.

The last set of essays analyses fissures in the feminist movement. Marilyn Frye draws parallels between ‘Whiteness’ and ‘Heterosexuality’, articulating how women of colour have felt for long that white feminists do not represent them. She urges white people to give up their ignorance by educating oneself, but being careful as to not make others the ‘object of study’. She refers to an instance where Audre Lorde was reading poetry, and a white woman who found Lorde culturally ignorant demanded that she spell out the name of goddesses referred to in her poems. Social class posits a problem too as men of colour often ignore women to stand within dominant groups on account of their sex.

Also read: Book Review: Dewaji—Making Of An Ambedkarite Family By Dipankar Kamble

Within the queer rights movement, Marilyn Frye draws parallels between ‘gay male culture’ and ‘heterosexual male culture’ as gay men are important to ‘masculinity’ and ‘male supremacy’. She explores antithesis between the politics of the gay civil rights movement and the lesbian feminist movement.

Within the queer rights movement, Marilyn Frye draws parallels between ‘gay male culture’ and ‘heterosexual male culture’ as gay men are important to ‘masculinity’ and ‘male supremacy’. She explores antithesis between the politics of the gay civil rights movement and the lesbian feminist movement. While gay male politics claims for maleness and male privilege for gay men, lesbian feminists seek to disable male privilege, erase masculinity, and reverse the phallus access. In the concluding essay ‘To be and be seen: The Politics of Reality’, the author looks for a definition of ‘Lesbian’, analysing the heterosexual and contradictory definitions of ‘sex’ and ‘sexuality’. The Politics of Reality looks at how women are oppressed as women, a member of a race or class, while men are not oppressed as men. It structurally codifies, defines and explores crucial concepts like oppression, sexism, and phallocentric culture; delving into conscious discussions surrounding whiteness, heterosexuality, male privilege and how the latter works against the feminist movement led by lesbians. The engaging philosophical discussion might seem heavy, but Marilyn Frye supplies enough real-life instances to make the process of learning, unlearning and relearning a worthwhile one.