Trigger Warning: Homophobic and ableist slurs

Arnold Bennett, an early twentieth century critic, claimed that Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own is not a feminist treatise since it fails to transgress the convenient apolitical boundaries within which her socio-economic positionality lies. Though Bennett’s rivalry with Woolf makes him an unreliable critic, there exists some truth in his review. It is hard to read her non-fiction through an intersectional feminist lens since her conclusions are based on various socio-cultural hypotheses.

In A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf uses various textual devices in the nucleus of the structure to distance herself from the narrative voice. In spite of assigning the medium of the first-person narration to Mary Beton, she produces a text that succeeds in emerging as a personal favourite even for womanist scholars like Alice Walker, the author of The Color Purple.

That virginia Woolf’s seminal text emerges as a memorable personal account for women across the global politic is somewhat problematic because it enforces a rigid brand of feminism belonging to the intellectual aristocracy upon women whose experiences are punctured by differences in class, caste, race, ethnicity, religion, and other pertinent determinants of social identity.

That the text emerges as a memorable personal account for women across the global politic is somewhat problematic because it enforces a rigid brand of feminism belonging to the intellectual aristocracy upon women whose experiences are punctured by differences in class, caste, race, ethnicity, religion, and other pertinent determinants of social identity.

Also read: Virginia Woolf And Her Plea For A Room Of One’s Own

The incorporation of canonical Western figures like Antigone, Cleopatra, Desdemona, and Clytemnestra further leads to the perpetuation of a Eurocentric model that universalises the female experience. This paints femininity as a monolithic gender identity. The popularity of her feminist output, therefore, replaces the fictions of masculine power by Virginia Woolf’s establishment of a European class-conscious, heteronormative, and ableist hegemony.

A Room of One’s Own poses an additional dilemma. Virginia Woolf’s usage of ableist and homophobic rhetoric makes an intersectional analysis of the text nearly impossible. Since language is an embodiment of referential meanings, it is important to evaluate Woolf’s manipulation of linguistic discourse and its consequences on cultural perceptions. Language is, after all, a tool that has the potential to exacerbate power imbalances or further submerge the marginalised in a crescendo of despair.

In the second chapter, Virginia Woolf writes, “A very curious fact it seemed, and my mind wandered to picture the lives of men, who spend their time in writing books about women; whether they were old or young, married or unmarried, red-nosed or hump-backed – anyhow, it was flattering, vaguely, to feel oneself the object of such attention, provided that it was not entirely bestowed by the crippled and the infirm – so I pondered until all such frivolous thoughts were ended by an avalanche of books sliding down on to the desk in front of me.”

The sentence is suggestive of her disapproval to flattery if the speaker is “the crippled and the infirm.” Such linguistic behaviour indicates covert hostility to physical disability and medical weakness.

Another instance of ableist antipathy is visible in Virginia Woolf’s Three Guineas, where she writes, “The poverty of the Christian who should give away all his possessions produces, as we have daily and abundant proof, the crippled in body, the feeble in mind.”

Virginia Woolf is a a globally acclaimed writer. The incorporation of violent diction in her works, which are widely read and cited, subtly enables linguistic constructions that affect our subjectivities. Richa Kohli contends that government schools in India are not equipped to provide quality primary education to students with disabilities. Institutions of higher studies, including several colleges of the University of Delhi, fail to furnish facilities for students with disabilities. To ignore the ableist rhetoric of Woolf’s non-fiction in critical analysis is to consciously deprive the disabled an agency in academia.

In Mrs Dalloway, Virginia Woolf temporarily portrays the homosocial bonding between Clarissa and Sally. Yet her non-fiction has traces of homophobic language. Whether its inclusion is conscious or inadvertent is irrelevant. Its existence itself can have damaging ramifications on contemporary movements of intersectional feminism.

One pertinent example from A Room of One’s Own is as follows: “The professor was nothing now but a faggot burning on the top of Hampstead Heath.” The term “faggot” is a profane term often used as a reference to a male homosexual.

In an article, Casey Legler, a homosexual man, writes: ““Faggots” are beautiful, magical, brave humans who have overcome the loss of an entire generation of their elders to HIV and Aids and who have, despite this, approached life with resilience, grace, and class, despite opposition, beratement, beatings, oppression, and exclusion from their families, their kin, their jobs, and their homes. And so being called a faggot is, in fact, a compliment of the highest order. Those of you who use it as anything less than a term of celebration are incorrect.”

Also read: Book Review: Orlando By Virginia Woolf

Though Legler has reclaimed a term that is generally used to vilify him and his community, it does not alter its negative connotations in twentieth-century British discourse. Language is a sociological set of referential symbols, and the recurrence of homophobic terminology in Virginia Woolf’s works unconsciously imbibes prejudices in contemporary readers.

The fact that the queer community is often forced into subordinated positionalities as a consequence of the dominance of the heterosexual form highlights the contribution of problematic vocabulary toward the process of making their existence invisible.

That is why the examination of language politics is integral in the assessment of the perpetuation of violence and abuse directed toward the marginalised in popular spaces: by normalising or ignoring hurtful vocabulary, we are encouraging insensitivity in everyday social interactions.

Abusive language directed at homosexual men encompasses feminine sexual behaviour or sodomy, in terms such as “ass bandit,” “anal assassin,” “bone smuggler,” “cock jockey,” etc. All the verbal linguistic emphasis is placed upon the poking element of sexual intercourse, an act performed upon the passive homosexual body.

Within this context, the heterosexual penis can use itself as an instrument of chastisement to control, use, and dissect the homosexual body to reclaim the conventional norms. The sadistic overtones in these terms serve to monumentalise the delivery of the implicit threat and suggest the reduction of the homosexual male to paroxysms of sexual capitulation.

Similarly, although some disabled people have reclaimed the term “crip” in the twenty-first century, “cripple” or “crippled” remains an abusive term. Its usage in Virginia Woolf’s works leads to the textual harassment of the people with disability. The reiteration of these terms in academic and popular discourses is effective in subconsciously perpetuating chauvinism in common parlance, thereby affecting the micro or the individual level as well as the macro or the social level.

More importantly, etymology of these profane terms reflects their patriarchal origins, and their constant usage in popular culture and academic discourse reinforces traditional norms that contemporary feminism endeavours to dismantle. How do we ignore these subtle nuances that problematise Virginia Woolf’s vision of feminism? The answer is: we don’t.

While it is integral to engage with her revolutionary work, it is simultaneously pertinent to interrogate the way in which subtle traces of abuse reinforce the conventional order established by a patriarchal society. If we desire to form and encourage a social movement to position feminist practices in contemporary postfeminist culture, we must review and revise seminal texts, such as Virginia Woolf’s pertaining to feminism.

While it is integral to engage with her revolutionary work, it is simultaneously pertinent to interrogate the way in which subtle traces of abuse reinforce the conventional order established by a patriarchal society. If we desire to form and encourage a social movement to position feminist practices in contemporary postfeminist culture, we must review and revise seminal texts pertaining to feminism.

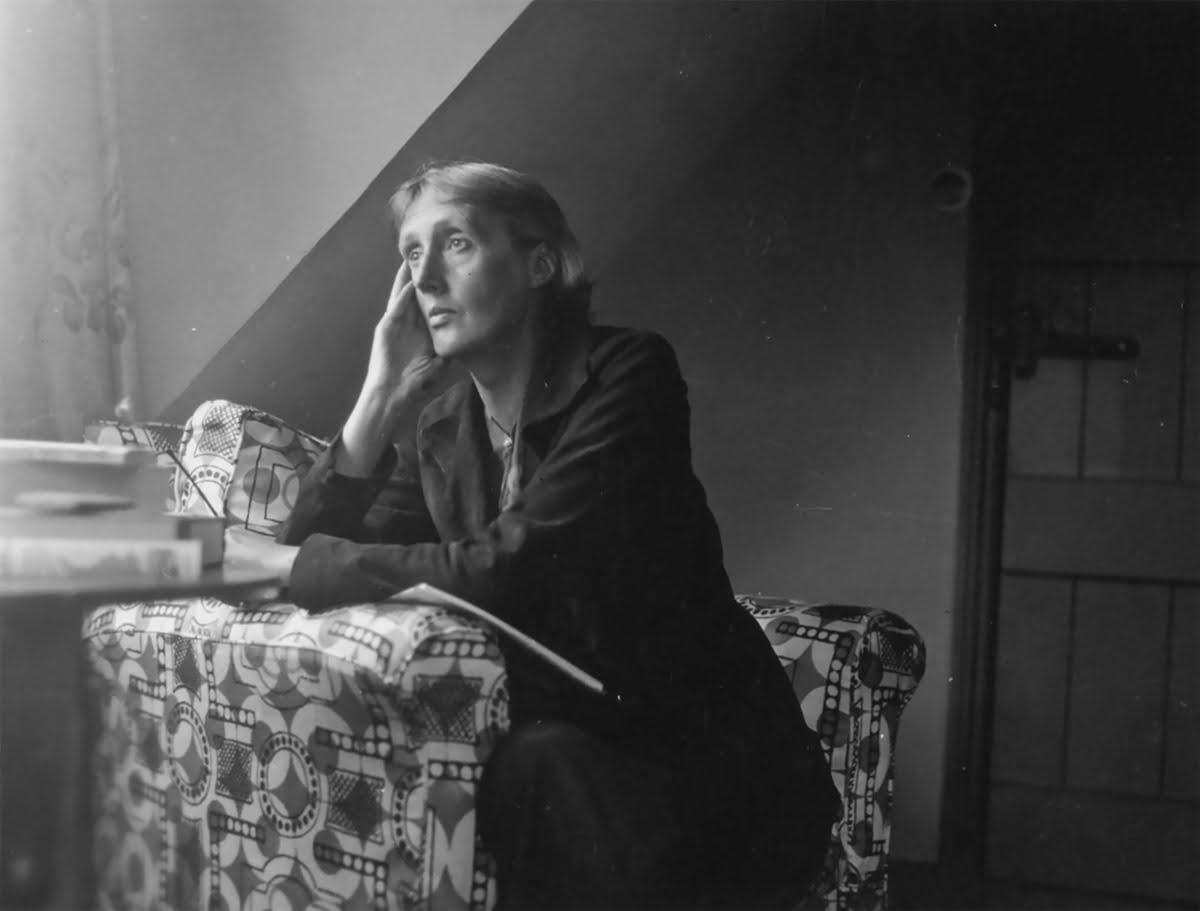

Featured image source: Medium

About the author(s)

Mridula Sharma is a researcher and a writer. Her work lies in the intersection of feminist theory, postcolonial studies, and popular culture.