Women’s life narratives reshape the contours of the disciplines of women’s writing and autobiographical studies. They reveal the myth of the universal category of women by exposing the formation of women as ‘products’ of patriarchal culture and history. The implosion of academic focus on life writing by women refutes Philippe Lejeune‘s understanding of an autobiography as ‘a retrospective prose narrative produced by a real person concerning his own existence’. Instead, this focus encourages the evaluation of narrative strategies used by women writers to undercut patriarchal biases about selfhood and subjectivity.

Rashsundari Devi makes a feminist statement about female solidarity and also reinforces Bracha Ettiger’s idea of “breast-envy” as opposed to Freudian insistence on “penis-envy.”

The trajectory of Rashsundari Devi’s Amar Jiban (translated as ‘My Life‘) reveals a distinct genealogy that recovers a sense of a lineage in tracing the psychological disorientation created by the loss of her mother. Women writers like Alice Walker and Harriet Jacobs have extensively discussed the idea of rootlessness caused by the death of the mother figure. However, Rashsundari’s attribution of significance to her mother, particularly when she mourns her inability to attend her mother’s funeral, transgresses the limitations of conventional representations. She makes a feminist statement about female solidarity and also reinforces Bracha Ettiger’s idea of ‘breast-envy’ as opposed to Freudian insistence on ‘penis-envy.’

Meenakshi Malhotra rightly argues that despite the problematics of codifying women’s life-narratives in terms of absence and loss, there is indeed a discernible motif of loss. Psychoanalytic studies suggest that this loss might be indicative of the loss of wholeness that a woman experiences after separation from her mother. Nonetheless, the loss exists and can be found in Rashsundari’s sacrifices for her family and bodily sacrifices for the fulfilment of her reproductive destiny by giving birth to eleven children in twenty-three years.

A cursory reading of her autobiography might suggest that she is a ‘victim’ of a phallocentric culture. That the functioning of patriarchy causes her suffering is obvious. However, the very act of writing an autobiography to document her experiences and articulate her subjectivity shows her position as an early feminist. Hira Naaz explicates Rashsundari’s feminist ethic by analysing her sociocultural ‘transgressions.’ One possible explanation of her courage in conservative society is her reevaluation of womanhood when she is deprived of a homosocial space following her mother’s death.

In the Fifth Composition of the text, she proceeds to discuss her state of starvation for two days: “I had been forced to fast the whole day…Nobody knew that I had not eaten the previous day.” This shows the consequences of the internalisation of cultural prescriptions as well as the extent of her family’s ignorance. Her struggle also outlines for contemporary scholars the physical harassment of women by patriarchy’s demand for their manual labour. E.P. Thompson uses examples similar to her’s to demonstrate how the conscious decision of food deprivation illustrates the integration of women into lineages of caste and class. This forms another motif of loss in Rashsundari’s writing and women’s writing in general.

Amar Jiban also endeavours to demonstrate the intersection of womanhood and education in nineteenth-century colonial India.

In this emancipatory narrative also lies a subtle attempt of the aestheticisation of manual labour in the kitchen. Swati Moitra aptly argues that there is nothing redemptive about housework. Instead of hailing Rashsundari as exemplary in her ‘expertise’ in domestic work and religiosity, contemporary scholars of women’s studies must critically examine the physical labour of the ‘domestic goddess’ as patriarchal exploitation. Rashsundari does not deliberately romanticise her misery, yet there are several suggestions, as Gopa Day argues.

Also read: The Caged Bird Who Sang: The Life and Writing of Rassundari Devi | #IndianWomenInHistory

Amar Jiban also endeavours to demonstrate the intersection of womanhood and education in nineteenth-century colonial India. Even after the introduction of education by Christian missionaries, the ‘zenana‘ system of education for girls remained unpopular and therefore ineffective in advancing women’s education. What made women’s education a central plank in reform proposals was the later social activism of liberal reformers like Ishwarchandra Vidyasagar. Rashsundari’s secretive pursuit of literacy is, however, detached from popular social reforms. She appropriates the socially sanctioned brand of religion in an attempt to strategically legitimise her desire to read.

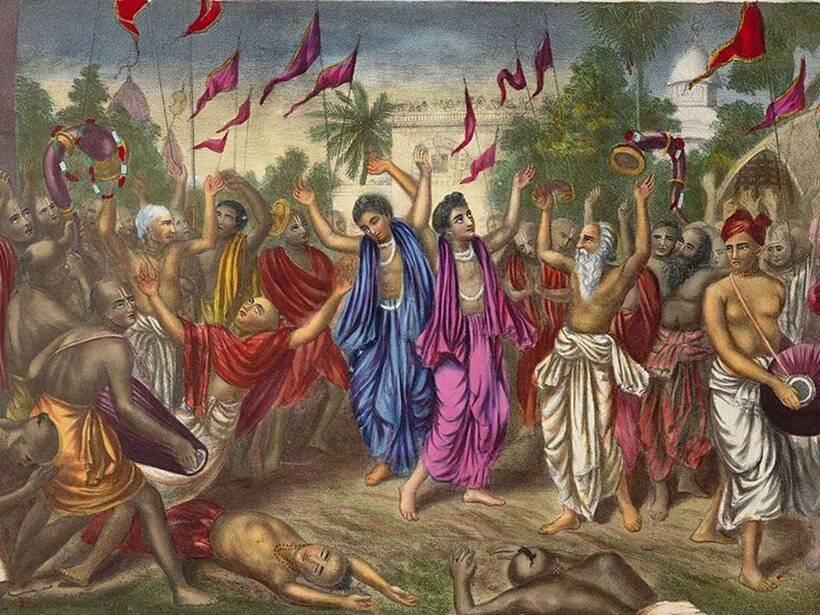

The origins of her recourse to religion go back to her mother, who advises her to seek refuge in Dayamadhab when she is scared. God thus becomes the symbol of an absent father. Her choice of the idiom of devotion within the space of Vishnu bhakti is somehow a means of articulation of the self. As a ‘bhakt’, she participates in the divine ‘leela‘ and renders supposedly mundane acts significant. For instance, her desire to read Chaitanya is catalysed when she sees herself reading the text in a dream. Such instances mould her pursuit of literacy.

Also read: The Caged Bird Who Sang: The Life and Writing of Rashsundari Devi | #IndianWomenInHistory

Tanika Sarkar writes that when Rashsundari ascribes her suffering to God’s will, she redefines her relationship with God. Her willed surrender highlights the despotism of God, rather than absolving it. Therefore, even as she patiently describes her subservient relationship with God, she emerges as the feminist protagonist whose success in learning to read and write enables her to undercut the patriarchal norms prescribed by religion. This is distinct from Saradasundari Devi’s celebration of God as either an all-merciful but not omnipotent entity or as an omnipotent but unkind entity.

The social documentation of Rashsundari’s micro-history narrative charts cartographies of struggle and produces subjectivity in terms of her subjection and subjugation. From a feminist standpoint, since her narrative emerges from a dis-privileged perspective, it has greater epistemological validity. It also reconfigures nineteenth-century India in the cultural imaginary from a woman’s perspective, enabling the contemporary reader to probe the functioning of matrimony in patrilocal households. Amar Jiban acquires a peculiar status as a minor narrative since it explicitly portrays the centrality of the issue of women’s education in changing social arrangements necessitated by reformulated patriarchies under colonial rule.

Featured Image Source: Indian Express

About the author(s)

Mridula Sharma is a researcher and a writer. Her work lies in the intersection of feminist theory, postcolonial studies, and popular culture.