Once when Sahir Ludhianvi was in college, the British Commissioner and Deputy Commissioner had come to attend an event. Sahir, who had earned himself a reputation as a poet and had throughout his college life been an active member, leader and also president of leftist student unions, was to recite his poetry on the occasion. However, when the time came, he greeted the audience and went on to state fearlessly, “As long as this Union Jack is flying above our heads, neither my friends nor I will participate or recite our poetry.”

This wasn’t the only incident of this kind, and incidents of this kind were the reason Sahir Ludhianvi had to constantly change colleges. He was a man whose pen knew no fear. He would constantly write for the downtrodden, he would persistently criticise the self-appointed guardians of religion, he would question the hypocrisy of the priests and the landlords, he would ruthlessly retaliate against the hoarders of wealth and wheat, the aristocrats who celebrated while the workers languished on the roads, the oppressor castes who crushed the farmers under debt, and men who despite being created by women, disrespected women every day.

Awarded the Padma Shri in 1971, with a commemorative stamp issued in his honour on his ninety-second anniversary, Sahir Ludhianvi’s pen made no hyperbole of the reality of life, and his art excelled in the progressive aesthetics of revolutionary poetry.

Awarded the Padma Shri in 1971, with a commemorative stamp issued in his honour on his ninety-second anniversary, Sahir Ludhianvi’s pen made no hyperbole of the reality of life, and his art excelled in the progressive aesthetics of revolutionary poetry. He revolts in perfect metering, criticises in the right rhymes and questions with reverberating phonetics. His was an oeuvre which was polished, an anger which was raw. Sahir brought critical reasoning to poetry. For he dedicated his pen to peasants and workers, he called out architectural monuments built in the name of love as exhibitions of royalty earned by committing atrocities against the oppressed — derogatory towards the love of the destitute, including the workers who built it.

Also read: Faiz Ahmed Faiz: An Immortal Poetry

The question that then arises is: If Sahir Ludhianvi would have been alive today, what would he have said to today’s lyricists, for whom writing lyrics is akin to objectifying and denigrating the female anatomy, for whom the marginalised do not have rights; lyricists who do performative wokenism and tokenism, or remain sycophants of the system?

In the book, ‘Sahir Ludhianvi The People’s Poet’, Akshay Manwani says, “It is impossible to reach out to Sahir the lyricist without approaching Sahir the person,” as he describes incidents that give us a peek into Sahir Ludhianvi’s life. After all, Sahir had written about how he wishes to return to the world, what he has received. As a child, Sahir had his own tantrums and as an adult, his own idiosyncrasies. As a kid, while drinking milk, he would ask for water to be added to the milk, and when water would be mixed, he would want it removed so that he could drink the milk. Later, after having become a renowned poet, before going to any mushaira, Sahir could never decide which attire to wear and if his cousins got ready before him, he would taunt them instead.

Born as Abdul Hayee on 8 March 1921, Sahir had taken the ‘takhallus’(pen name) of Sahir Ludhianvi. ‘Sahir’, for he considered himself as ‘one amongst several poets’, and ‘Ludhianvi’ to depict the connection to his birthplace Ludhiana. Incidentally, ‘takhallus’ also translates to “get rid of” and Sahir Ludhianvi had to get rid of the city. Born into a landlord famil, his father, debauched into wantonness, wouldn’t want Sahir to get educated. Meanwhile, his diligent and loving mother wanted Sahir to study sincerely. Having had to go through the trauma of a broken family as well as court trials related to his custody as a child, these experiences coupled with his concern for the marginalised, shaped his poetry.

Consequently, in college, his poem ‘Where Workers Reside’ was published in an underground newspaper called Kirti Lehar. Sahir Ludhianvi, settled in Lahore, completed ‘Talkhiyaan’ and edited Urdu magazines. Sahir was an active member of the Progressive Writers’ Association. And when he wrote against the arrest of progressive writers and kept on writing for the right causes even post the partition, the government issued an arrest warrant for him. Consequently, in June 1948, Sahir fled from Lahore to Delhi, and then later to Bombay(present day-Mumbai). The aftermath of the partition left a massive impact on Sahir who feared that any legal independence earned at the expense of societal bigotry would intensify into a predicament of an even colossal magnitude in the future. However, instead of letting the bitterness devastate him, he chose to hold the pen and yearn for a better future.

When transitioning from poetry to songwriting in Bombay (now Mumbai), Sahir Ludhianvi faced several challenges and hurtful remarks because even though people trusted his poetry, they doubted if he would be able to write songs for movies.

When transitioning from poetry to songwriting in Bombay (now Mumbai), Sahir Ludhianvi faced several challenges and hurtful remarks because even though people trusted his poetry, they doubted if he would be able to write songs for movies. Given the heritage of oral-verses passed across generations, the systemic violence of dominant castes creating abysmal rates of literacy, especially among the marginalised communities who majorly form the working class, and the fact that tunes aren’t limited to geography but lyrics and language which change across regions tend to be, lyricists have not been accorded acknowledgement in our country.

Also read: Where is the Woman’s Voice? Sexism in Hindi Film Music

Mainstream Hindi cinema has hitherto disguised the pen, and further, endeavoured to manifest that it is the actor composing and singing the songs impromptu. It was Sahir who first demanded that the songwriter’s name should be mentioned on the records. He stood staunch before the radio channel Vividh Bharti to name lyricists along with other artists while playing film songs. And unlike his contemporaries who wrote songs to fit the tune and the script, Sahir expressed himself organically and became the first lyricist to receive royalties from music companies. An anti-war poet, from his work ‘Shadows’ which uses words in a flashback form along with serial photography to show the realities of war, to his poem ‘Oh Civil Humans’ which says that, ‘War itself is the problem, what solution will war give, all it will give is fire and blood today, hunger and scarcity tomorrow”, Sahir Ludhianvi taught us to hold the pen with passion and responsibility, to leave the surface-level rose-tinted smugness of the privileged. Exactly how in his lyrics for the movie ‘Pyaasa’, he wrote, “Jinhe naaz hai hind par woh kahan hain?”

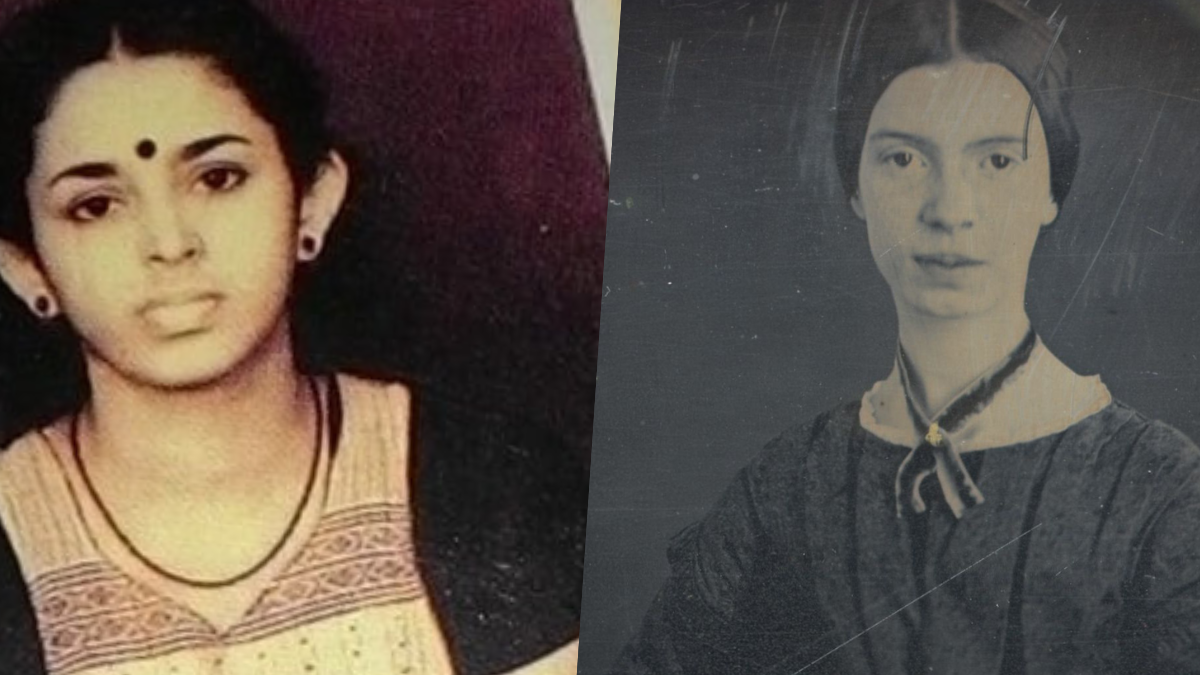

Featured image source: Tribune India

About the author(s)

Ankita Apurva was born with a pen and a sickle.

Thank you so much. 🙂