The study of religion and gender together remains a largely unexplored field. It is important to understand the way in which gender is established and performed under the influence of religion and religious practices—something that the feminist movement aims to recognise, redefine and rewrite (wherever possible).

Emile Durkheim in his book Elementary Forms of Religious Life defines religion as “a unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things”. Scholarly conversations surrounding religion highlights one important aspect i.e. the definite control and influence of religion on the social life of individuals. Gender is a social construct. It is an aspect of identity that is gradually acquired through the process of socialisation.

Also read: Handmaid’s Tale In The Hindutva Manu Rashtra

“Gender is the cultural meaning and form that the body acquires, the various modes of the body’s acculturation”, says Judith Butler. The faithful performance of prescribed rituals of gender over and over again through one’s lifetime is essential for maintaining this social order. Therefore, one can state that gender and religion remain intimately intertwined with one another, as both the institutions serve the purpose of continuing social order. Religion provides the moral sanction, gender gives action to this sanction. However, there is the ‘feminist dilemma of religion’ i.e. the assumption that religion has an inherent incompatibility with the interests of women.

One can state that gender and religion remain intimately intertwined with one another, as both the institutions serve the purpose of continuing social order. Religion provides the moral sanction, gender gives action to this sanction. However, there is the ‘feminist dilemma of religion’ i.e. the assumption that religion has an inherent incompatibility with the interests of women.

However, empirical evidence suggests otherwise. The recent resurgence of religious fundamentalism across countries is an example of that.

Religion as oppressive

An enquiry into the relationship of religion and gender aims to show how orthodox religious practices shape gender roles, norms and behaviours by providing them with a moral sanction. Religion also sometimes plays the role of marginalising women from society by deeming them as inferior and providing sacred justifications of the same.

Ancient texts like the Manu Smriti become relevant in this conversation. The role of a woman as defined in ancient Hindu scriptures rests on their capacity for motherhood and thus respects women only insofar as they do their ‘duty’ of reproduction. As a consequence, every woman is to be ideally viewed as one’s mother/ sister/ wife/ daughter. The text further opines that women are lucky to be able to give birth and motherhood is a woman’s primary dharma i.e. responsibility- it is the reward for her sins from the past life, thus achieving karmic equilibrium over the lives. The reason why an ancient text is given importance in the discussion lies in the fact that a Hindu woman’s life- choices, wishes and decisions are informed by “culture and tradition” and even the Constitution of India has framed its laws on marriage, succession and other issues for Hindus in keeping with this text.

Taking the example of Jainism, it can be noted that women are considered to be inferior beings. The Digambara sect of Jainism argues that women are inferior to men and cannot achieve salvation. They provide four main reasons for this claim, starting from women’s inability to be commit morally corrupt acts from which they can gain salvation. Secondly, moksa can only be achieved by being monastic, but being monastic includes giving up clothes, which women cannot do. Along similar lines, the argument states that since women are not allowed to participate in debates, they cannot attain salvation through thought. Another argument is that women’s inferior social position reflects her inferior spiritual position- this is why only sons and not daughters can inherit a king’s throne. Religion continues to influence the realms of marriage and family- thus taking over a large space in the private life of individuals.

Bargaining with Religion

It is important to note that feminist theory on gender is diverse. Contemporary feminist literature focuses on intersectionality, interdisciplinary and transnationalism. Scholarly work on gender and religion wishes to analyse gender as a social category; and understand how gender is produced, reproduced, taught and negotiated, and transformed in accordance with religious sanctions. While religion is often understood to be conservative and restrictive of the individual—especially women’s in regards with agency, it is important to note that religion too is shaped by gender logics, where norms are articulated, negotiated, and subverted.

Nisha Pahuja’s movie “The World Before Her” beautifully shows how young girls assert their agency by being a part of the training camps –Durga Vahini; run by the Vishwa Hindu Parishad. While they remain confined in the larger religious domain by having to adhere to the strict rules of being a ‘perfect Hindu woman’, being a part of these camps gives them the choice and agency to delay their marriages. This is where it becomes important to highlight how one can be an activist without disturbing ideals of Hinduism, or challenging patterns of inequality at home. Women resist not just among their kin, but also from the external agents, albeit by perpetrating the patriarchal system at some level.

The recent anti-CAA/NRC protests across the country highlighted a similar trend. Muslim women from Shaheen Bagh sat in agitation against the Act for more than 30 days. As women–homemakers, primary caretakers of children; clad in the hijab, they not only asserted their identity as Muslims but did that in synchronisation as women. The women of Shaheen Bagh represented the confluence of religion and feminism- agitation, political movement and moral sanctions coming together. What does become important to look at is how women and other gendered bodies function under the caste schema. While tradition will have it that the Brahminical conceptions of family, femininity and sexuality are the parameter for what constitutes the “normal” and “good”, Dalit feminist critique aims to dismantle such understandings.

The women of Shaheen Bagh represented the confluence of religion and feminism- agitation, political movement and moral sanctions coming together. What does become important to look at is how women and other gendered bodies function under the caste schema.

Also read: Love Jihad Law: Making Hindu Women ‘Nirbhar’ In ‘Aatmanirbhar’ India

It is important to note that religious women can be agents when operating within seemingly oppressive cultural and institutional contexts. In aggregate, these examples show that practices, and social institutions could be simultaneously sites of oppression and empowerment and resistance.

Religion and Feminism: Can they work together?

It becomes clear that there is a need to use an intersectional lens to analyse real life instances of feminism; challenging the assumptions about gender and religion; and expand the definitions of agency, oppression, and social change.

Gender and religion are not separate, and neither is feminism and gender. These institutions and movements continue to retain their complex intersections, without assuming the precedence of one over the other. Avishai remarks that to understand Jewish women’s agency or construction of femininity in religions, it is necessary to view how these categories are created, and transformed within certain historical and cultural contexts (Avishai et al. 13). Issues of identity, resistance, agency, and change remain fluid categories that change and adapt themselves according to the changes around them. Thus, to reiterate once again, there remains a need to explore the relationship between gender and religion that keeps in mind empirical evidence, bargaining, and resistance to not only re-address issues of gender equality, but also address them in a way that allow ‘the best of both worlds’.

References:

- Avishai, O., Jafar, A., & Rinaldo R. A Gender Lens on Religion. Gender and Society, February 2015, Vol. 29, pp. 5-25. Sage Publications. JSTOR, www. jstor.org/stable/234532. Accessed 31st October 2020.

- Butler, Judith. “Sex and Gender in Simone De Beauvoir’s Second Sex.” Yale French Studies, no. 72, 1986, pp. 35–49. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2930225. Accessed 31st October 2020.

- Durkheim, E. Elementary Forms of the Religious Life. New York: Collier Books, 1961.

- Jaini, S.P., Gender and Salvation: Jaina Debates on the Spiritual Liberation of Women. The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies. November 1993. Vol. 16, pp 202- 209.

- Kandiyoti, D. Bargaining with Patriarchy. Gender and Society, Vol. 2, No. 3, Special Issue to Honor Jessie Bernard. (Sep., 1988), pp. 274-290. SAGE Publications. JSTOR, http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0891-2432%28198809%292%3A3%3C274%3ABWP%3E2.0.CO%3B2-W. Accessed 31st October 2020

- Madan, T.N. Whither Indian Secularism?. Modern Asian Studies, Vol. 27, No. 3 (Jul., 1993), pp. 667-697. Cambridge University Press. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/312965. Accessed 31st October 2020

- Menon, N. Seeing Like A Feminist. Zubaan, 2012.

- Orit Avishai, Theorizing Gender from Religion Cases: Agency, Feminist Activism, and Masculinity, Sociology of Religion, Volume 77, Issue 3, AUTUMN 2016, Pages 261–279. JSTOR, www.jstor.org. Accessed 31st October 2020.

- Sidhinathananda, Swami. “Chapter 9.” In Manu Smruti, by Swami Sidhinathananda. Thrissur: Mathrubhumi, 1988.

Aishwarya Mall is a 23 year old woman living in Gurgaon. She is currently part of the Young India Fellowship at the Ashoka University. Her interests lie in academic studies of gender, health and education. She loves to spend time in the sun, listening to music and drinking copious amounts of chai.

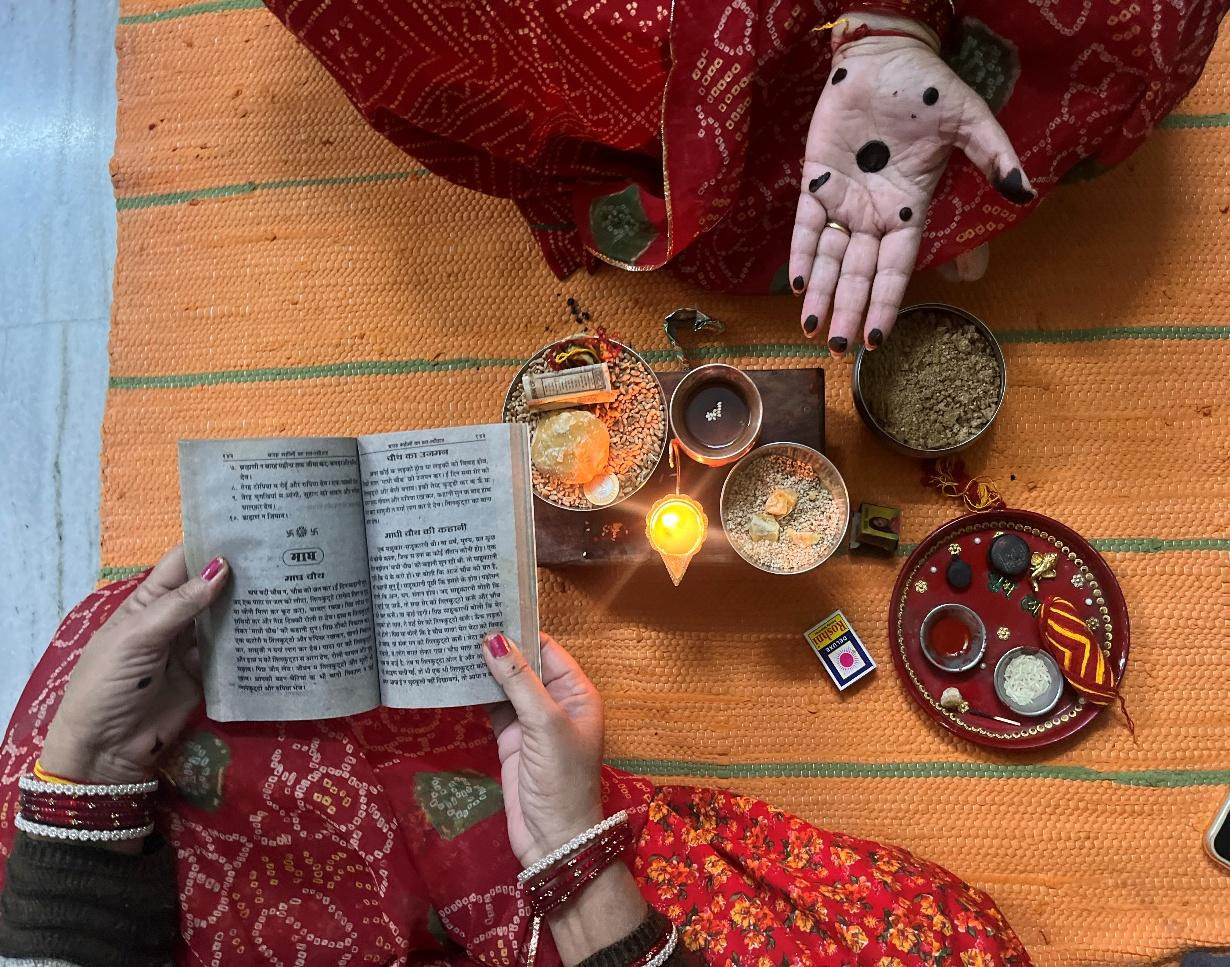

Featured image source: Outlook India

Sometimes it hard to differentiate your writings from satire. The most opressive religions are feminist and the religion that worships women are the most oppresive for women?