In a letter dated July 18, 1947, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi wrote, “If only women of the world would come together they could display such heroic non-violence so as to kick away the atom bomb like a mere ball…” Gandhi is often stated as the forbearer of emancipating women from societal restraints and taking part in the nationalist movement at a time when they were hidden behind the purdah system and locked doors. But looking at Gandhi in the literature of contemporary interpretation provides us with the prospect of a different perception of his picture, one of an inconsistent liberal with contradictions shadowing his actions due to an inclination towards a patriarchal framework.

Madhu Kishwar notes how Gandhi differed from the 19th century reformers in that he did not view women as passive agents requiring a third party intervention to change. Instead he saw them as active agents who could bring for themselves a transformation in their social standing. Gandhi adhered to the belief that one was responsible for one’s own emancipation and this belief became foundational in structuring his view of the Indian woman.

Essentials of an Ideal Woman

For Gandhi, the inspiration was an essentialist image, created by invoking the icons of Sita, Draupadi and Damyanti. These were the three standards of womanhood wherein Sita or Draupadi were not to be read as ‘helpless creatures’ but one with superior moral courage. As such, he saw women’s virtue as their greatest strength. But for this to be so, it relied on the notion that women could only be measured with respect to their chastity and virtue. They became holders of the ultimate moral power, bearing the responsibility to change and highlighting their sacrificial and self-suffering constitution.

The idea of non-violence consequently became the super power of the Indian woman. Gandhi observed how his wife and his mother resisted against any wrong doings in their life, silently and passively. Women came to ‘contain’ this feature and were called to join the movement, to balance out the aggressiveness of men who lacked these ‘feminine qualities’.

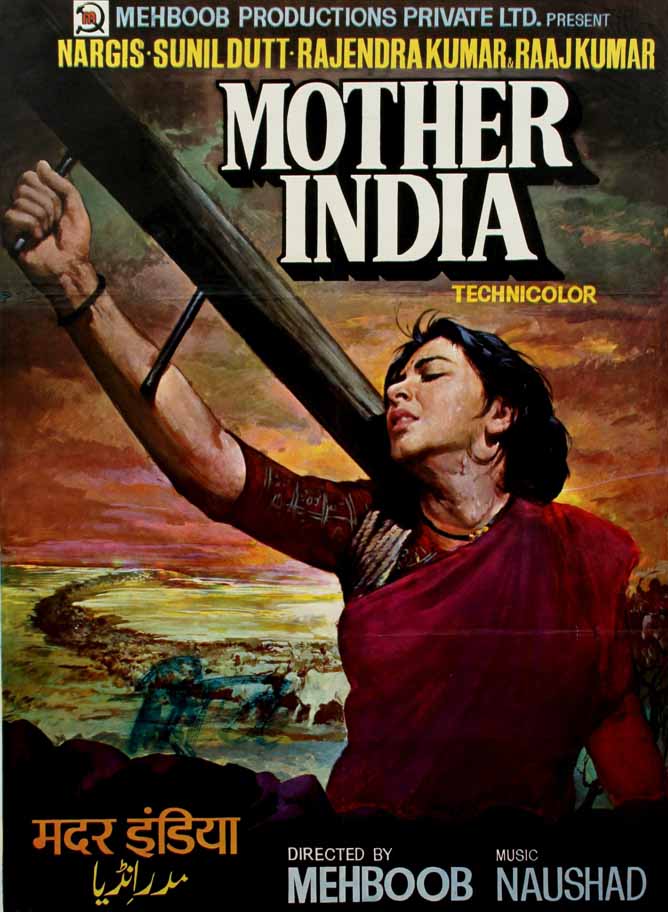

But what was the consequence of such an image? When one holds the power to define what something is, they also hold the power to decide what something is not. In establishing the morally strong image of a woman, Gandhi was able to dictate what was to be seen as right or wrong in society. Women came to be seen as the embodiment of sacrifice which simply reinforced their image as ‘accommodative’, a reflection of which can be found even today in the (in)famous image of Mother India. Women were now to sacrifice their beings in service of the country.

The Body and the Politic

Gandhi’s conception of the woman (and the man) and the way these two were to interact in society can be read as not based on any protest against the patriarchal structure but as in the interest of the society. Sexuality and women’s sexuality in particular seemed troubling for Gandhi as he often endorsed his view of potential to be found in widows as ‘servant of the nation’. Even as he argued that women had the right to say ‘No’ to their husbands and protest against being seen as ‘sex objects’, Gandhi would in the same breath celebrate the noble women for the purity and chastity she had.

As elaborated by Ashwini Tambe in her article, ‘Gandhi’s ‘fallen’ Sisters: Difference and the National Body Politic’, by linking his own body and the body of the people to the movement, Gandhi was able to equate control over all bodies to the success/failure of the movement, creating desexualised routes of participation for women. This resulted in an anti-sexual mode of the nationalist movement to arise.

Much of Gandhi’s writings on the topic of sexuality denied women the possibility of having any sexual drive and sexual fulfillment for celibacy played a central role in his worldview. A sharp dichotomy was set between men, as highly sexed individuals and women as lacking any sexual needs and responsible for sexual restraint. The highest moral pedestal was then of course given to the ‘universal mother‘, a woman who negated sexuality and was a ‘pure creature’. Women’s bodies became linked to the national movement in the most intimate ways possible while at the same time creating a detachment from their own sexuality.

What of the sex worker?

The sex worker is nowhere to be found when one talks of Gandhi’s contribution to women empowerment, even though in 1921, 350 sex workers in Barisal, a district in east Bengal volunteered to become members of the Congress party. The women had also contributed to the Tilak Swaraj Fund, set up to support Congress’ activities. But when they wished to seek office, Gandhi refused citing the reason that anyone who did not approach with pure hands and a pure heart could not officiate at the altar of Swaraj. They were then ‘advised’ to take up hand spinning.

Sex workers were the antithesis of all that Gandhi had conceptualised as the Indian woman. Feminist scholars such as Geraldine Forbes and Sujata Patel stay unsurprised, for Gandhi’s ability to mobilise such an unprecedented number of women in participation was based on a strict adherence to standards of what constitutes respectable femininity.

Women have always been an intrinsic part of Gandhi’s life. And Gandhi himself as a subject of study is a complex and difficult subject for his writings and opinions often change, reflecting his ever changing attitude. Branding him as a ‘feminist’ without understanding his motives would then be too uncritical an approach. Looking at Gandhi from a feminist lens provides us with those instances which have been overlooked or cleared off his image. This would be violence in itself for Gandhi had freely linked his personal to the political and opened his life to the public and its critique. A leader as controversial as Gandhi must not be read in the whitewashed version of today’s time.

Also read: Yes, Gandhi Was No Feminist But Should We Cancel Him For It?

Katyayani Singh is pursuing her Master’s degree in Philosophy from University of Delhi. She has a keen interest in philosophy, art and psychology with an inclination towards phenomenology, existentialism and embodied cognition. Katyayani can be found on Instagram and can be reached at katyayanisingh@gmail.com.

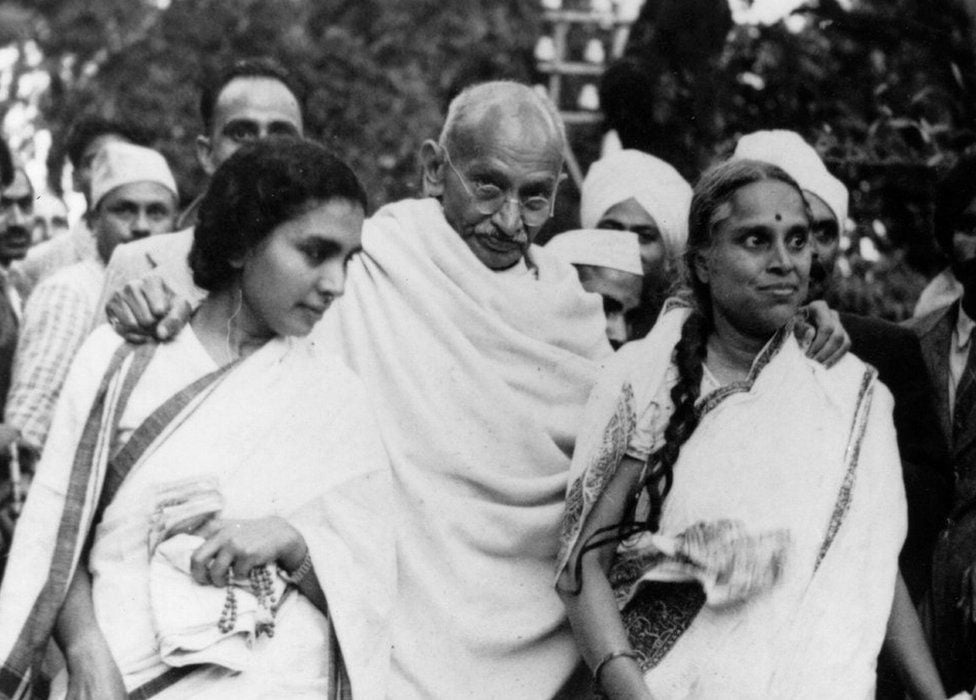

Featured Image Source: Some of Gandhi’s closest aides – such as his associate Sushila Ben (L) and his doctor, Sheila Nayar (R). Fox Photos/Getty Images