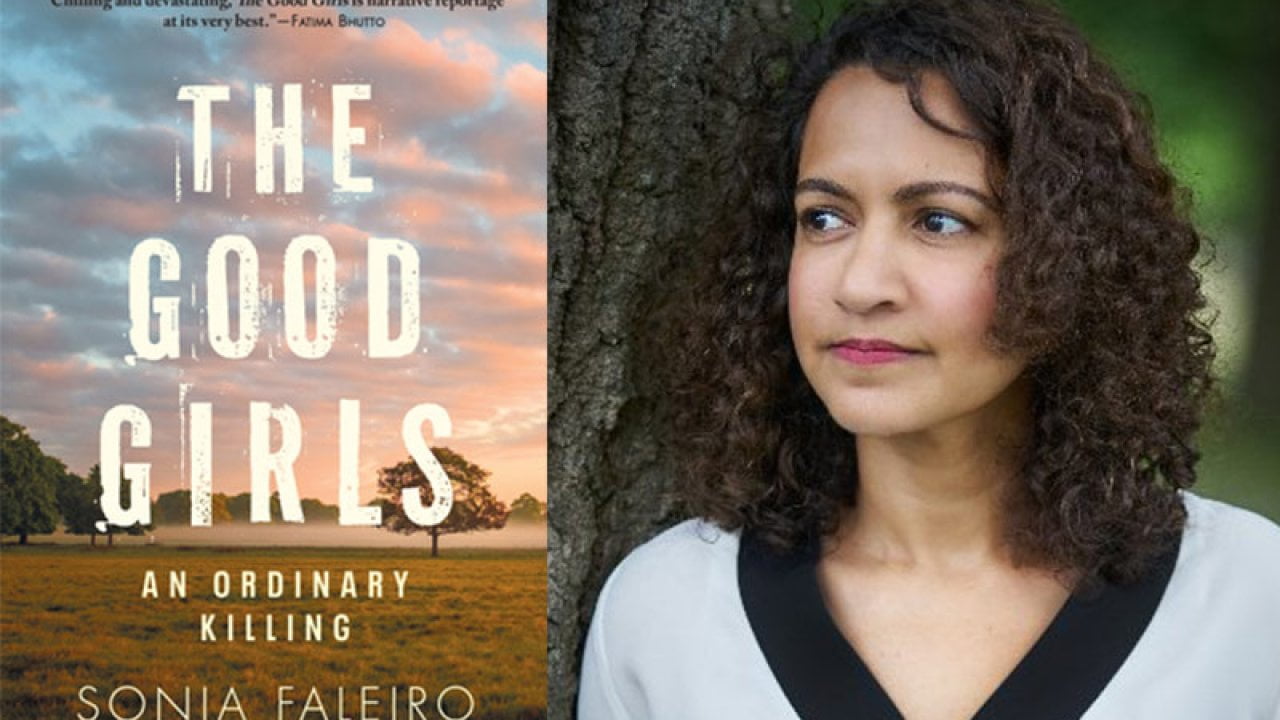

An excerpt from the Manusmriti is indeed a most fitting epigraph to Sonia Faleiro’s The Good Girls: An Ordinary Killing, a deeply harrowing and meticulously researched novelisation of the— ‘ordinary’—deaths of two teenage girls in Uttar Pradesh that occurred a few days after Narendra Modi came to power in 2014.

Faleiro, in an explanatory note inserted at the end of this masterful piece of narrative journalism, says that the 2012 Delhi gang rape and murder case had impelled her to undertake an investigative study of sexual violence in India—a study that would help develop an understanding of the specific socio-economic and cultural conditions that made misogynistic cruelty a banal reality in the country. In that sense, her epigraph is a sharp and telling indictment of a punitive and necessarily patriarchal caste society built on surveillance, shame, and the compulsion to maintain a choke-hold over women’s sexual agency—all veritable legacies of the Laws of Manu.

In 2014, two girls—whose names have been changed to Padma and Lalli (aged sixteen years old and fourteen years old respectively) in Faleiro’s book—were found hanged in the village of Katra in Badaun, UP. The horror of this incident was encapsulated in the haunting visual of the girls’ bodies suspended from a tree, and the event itself was widely apprehended by mainstream media as a high-profile case of rape and murder.

The Good Girls is a powerful interrogation of the violence bedevilling that site which Indian girls and women call ‘home’ and a searing examination of the unspoken terrors and insurmountable burdens of honour and shame that are embedded within the structure of the Indian family.

However, in the note at the end of her book, Faleiro goes on to say that in the course of investigating the Badaun hangings, she began to unearth a heartbreaking story of violence that was quite different from the one she had heard till then. The particular sorrow of this narrative that eventually revealed itself lay in the discovery that, as Faleiro puts it, “an Indian woman’s first challenge was surviving her own home.” The Good Girls, then, is a powerful interrogation of the violence bedevilling that site which Indian girls and women call ‘home’ and a searing examination of the unspoken terrors and insurmountable burdens of honour and shame that are embedded within the structure of the Indian family.

Also read: Book Review: Dewaji—Making Of An Ambedkarite Family By Dipankar Kamble

In Faleiro’s emotive yet essentially journalistic account, the events following the discovery of Padma and Lalli’s dead bodies are recounted in close detail, and it is this methodical scrutiny that visibilises the logical inconsistencies in the recorded narratives presented by the villagers of Katra. These gaps in turn shape our understanding of the villagers’ diverse, and often conflicting, motivations as they interact with the UP police as well as the CBI over several months during the official probe into the incident. The probe, of course, is a crucial object of study in The Good Girls, exposing as it does a range of pernicious biases, infrastructural inadequacies, and deep-seated inequalities rooted in the institutions shaping Indian law and order.

Faleiro’s extensively researched narrative carefully highlights the numerous ways in which all the systems in place—from forensic analysis and mainstream media coverage to the apparatus for criminal investigation and redressal—fail to approximate the elusive ideal of justice for the deceased girls.

The Good Girls looks us straight in the eye and asks: what do we assume about the behaviour of ‘good’, ‘chaste’, Hindu girls in rural India? What are the annihilatory capacities of such assumptions governing notions of shame and honour in women’s lives?

The origins of these persistent structural failures in modern India, in many ways, can be traced back to the Laws of Manu. Corpses, for instance, are considered to be impure in Hinduism, and the task of handling them is assigned to only Dalits. As a result, at the local hospital in Katra, a sweeper is made to perform all the post-mortems (though his salary remains that of a sweeper’s), with no medical practitioners present. This purity-pollution paranoia summarily botches up the forensic report and goes on to constitute one of the most consequential failures in the investigation process.

Similarly, a cynical journalist in the immediate aftermath of the tragedy, deciding that this was an ‘ordinary killing’, categorises the case as a ‘crime of caste’ because it confirmed existing negative assumptions about Yadavs, who were the main accused: “everyone…knew that Yadavs hurt people.” The interrogation of this impulse—distributed in varying degrees among the villagers, the police, and the media—to indict the Yadavs as rapists and murderers, in the absence of any substantial evidence, is also an essential element in The Good Girls that informs Faleiro’s scrutiny of the ascription of criminality in India based on casteist attitudes. In a telling statement towards the end, the five accused are quoted: “This is what it meant to be poor…low caste and above all, Yadav.”

Also read: Book Review: The Politics Of Reality By Marilyn Frye

Faleiro’s true-crime narration, despite revealing all the facts only gradually, makes one thing very clear at the very outset: a sexual act was performed which led to this tragedy. In many ways, therefore, sex itself becomes the thematic centrepiece of this study which pivots the villagers’ frenzied discourse upon various modalities of consent and violation, agency and seduction. In doing so, The Good Girls looks us straight in the eye and asks: what do we assume about the behaviour of ‘good’, ‘chaste’, Hindu girls in rural India? What are the annihilatory capacities of such assumptions governing notions of shame and honour in women’s lives? How do girls come to dread their sexuality, how do they come to fear their fathers and uncles and brothers? How does family become the original site of policing and repression? And finally, where do they go when home is no longer a safe place?

Adreeta Chakraborty currently pursuing an MA in English at Jawaharlal Nehru University while working part-time as an editor. Follow her on Instagram, Twitter and LinkedIn.

Featured Image Source: Film Companion