I remember the first time I read Dr. Meena Kandasamy. A 20 yr old literature major student hunching at the last bench unaware, unsuspecting of the way the words on the paper would change her. Mascara from her first published collection of poetry, Touch (2006), left the class dumbfounded, just like her recent book has left me.

I am tempted to call this anything but a review — it is an ode of appreciation, a love letter, a fan account. And she renders me permission to negate any expectation of neutrality that a review presupposes when she talks about an instance when a white filmmaker was preferred to film the plight of the surviving Tamil Tigers for a balanced perspective. She says, “I do not have that with all my brown skin. I do not have even the semblance of neutrality here.”

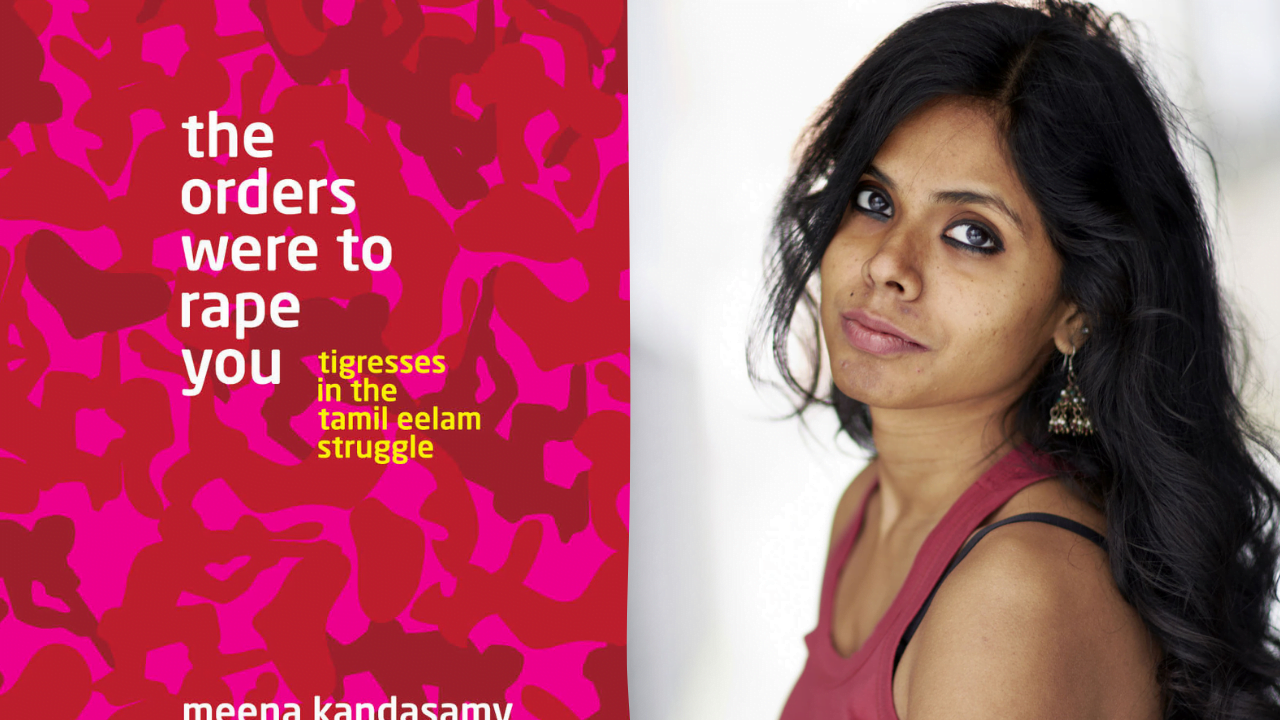

This book — a collection of essays, transcripts, translated poems, archive — is Dr. Kandasamy’s quest to immortalize women in the armed struggle for Tamil self-determination in Sri Lanka. Even though the war ended in 2009 officially, the infliction of trauma and violence on the Tamil population in Sri Lanka continues to this day. Dr. Kandasamy has been a relentless voice against the Sri Lankan regime and the genocide of Tamilians under the garb of a ‘war on terror’ that was aided by the complicit Indian Government. When asked, in an interview in 2013, why she continues to criticise Sri Lanka, she says: Why do I do this? Because I’m informed of what’s going on the ground (in Sri Lanka) and because my anger would break me if I remained silent and helpless. And that is all you need to know about the force that drives the compilation of this book.

Also read: Book Review: When I Hit You, Or, A Portrait Of The Writer As A Young Wife By Meena Kandasamy

Her ‘childhood history of adulation and fan-girling over the Tigresses’ shapes the endeavour and questions the white, patriarchal value assigned to so-called unbiased narratives. She questions the need for neutrality to tell a story. And that questioning often opens the door for the reader to witness unexpected moments of introspection she has out loud. As I part take in this soliloquy-esque interrogation of the facade she dons to prevent a glimpse of the toll this project takes on her, I allow myself to drop my own pretence of distanced sympathy. Making herself vulnerable, she draws out the humanity in me before we hear the stories of the women. Almost preparing me for something she could not prepare herself for.

But in her introspection, I also discover the larger political questions she is asking. How does one expect balance and sound political judgment when rape and physical violence is being recounted? What does such a patriarchal expectation say about our humanity that prefers political correctness over the dignity of survivors? Her own account of vulnerability while filming the women negates the idea that the perusal of truth — the quest men have monopolized for centuries — is an objective one.

“Nothing had prepared me to brace for the reality that these powerful women would be so vulnerable.“

Also read: Meena Kandasamy’s ‘Ms Militancy’ And Its Poems Of Resistance

Growing up with admiration for the courage of the Tigresses, young Meena finds ‘borrowed courage’ to live in a country that did not have a place for young women like her. The mastery of the Tigresses as sharp shooters painted a vision of valour of them that she chases as she films the documentary only to be met with a reality that begs to differ. Stateless and citizens of nowhere, these survivors of war crimes are at their most vulnerable conditions. But the beauty of these women — the wife of the Tiger, the Tigress and Dr. Kandasamy, herself — is that they straddle between valour and vulnerability, adhering to neither patriarchal tropes of gallant soldier or abla naari. They are both: one moment burning with a fire that could burn down empires with their wrath and the other, agonising for their people and self.

This co-existence of valour and vulnerability is beautifully expressed by Capitain Vaanathi in her poem Get ready for battle:

Look! There, is a flood of blood,

your sister holding her gun out to you.

Take her weapon.

Walk in her footsteps.

It breaks away from the patriarchal hangup that strong, powerful women are characterized by their lack of vulnerability, instead exclaims that it is fueled by their knowledge and acceptance of it.

The book also has translated poems of women who fought on the battleground for Tamil Liberation. After a brief explanation of why and how Dr. Kandasamy finds these poems and what they mean to her, she offers her analysis of the role of these poems in the female militant movement. She asks if the existence of these poems convince us that these were young, informed, politically aware women instead of merely ‘innocent recruits, helpless recruits’. In Captain Vaanathi’s ‘The Unwritten Poem’, she beckons the reader to ‘write’ almost similar to her call to take the weapon in Get ready for battle.

As the poem unfolds, you realise, the poem that is unwritten, is the story of liberation in which her role remains incomplete. And it is her call to bear arms when she says, “Write/ my poem / that I leave / without writing” almost metaphorically calling you to wield the pen like the sword for the cause of liberation and continue what she couldn’t live to see.

Look into my unwritten poem

and you will see those who knew me,

and those who understood me,

and those who care for me,

and those who loved me,

all of them.

Even in this incomplete version of the liberation dream, everyone is found in it. The quest for freedom was one of violence and militancy but also a place of love, care and empathy from where they drew the strength. The solidarity that envisioned and vowed to see their dream come to life.

Also read: The Poetry Of Meena Kandasamy: A Tool of Political Dissent

About the author(s)

Hannah is a writer running from pillar to post making sense of culture and conversations. She is mostly found convincing people to watch Nanette by her namesake. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.