Trigger Warning: Rape and sexual assault

Allegedly, a play lying at the intersections of sexual violence, justice and all our personal predicaments and inferences in between, seeks to ask questions that have never been answered and remain unanswered at large. It teaches us the different faces of consent to start with, such as how consent goes beyond just a yes or a no. Allegedly attempts to provide us a more a nuanced perspective: How consent is so much more than what we’ve been conditioned into believing: that it cannot be boxed. Allegedly is a play which leaves the audience questioning and uncomfortable even after it is well over. Ultimately, all comes down to questioning our inability to truly believe women.

First commissioned by the Indian feminist publishing house Zubaan Books in New Delhi, Allegedly has been performed at universities and other platforms in India since 2018. Due to present circumstances of the global pandemic, the play has been redefined and changed from its original form to be turned into a performance online.

First commissioned by the Indian feminist publishing house Zubaan Books in New Delhi, Allegedly has been performed at universities and other platforms in India since 2018. Due to present circumstances of the global pandemic, the play has been redefined and changed from its original form to be turned into a performance online. As a result of this, it has also resulted in the play redefining its relationship and interaction with its audience and spaces online.

Allegedly follows a discussion between a woman and her friend: presumably a journalist. As they discuss the details of what happened that night, we notice how the friend asks her questions about little details: questions that aren’t even relevant to the case, questions that beat around the bush and take our focus away from what the man did, and towards the woman: “What bra was she wearing,” for instance.

Also read: Unpacking The Reasonable Woman Standard – A Case To Respect Survivor’s Lived Experience

The entire play is filled with questions: questions towards a woman who was “allegedly” raped 16 years ago. As the play progresses, the audience is left baffled at the inability of the journalist to truly believe her. There’s a play on the word “Allegedly” here: Allegedly means the reporting of a crime that has not been proven by facts yet. Assault against women, mostly owing to the lack of evidence other than the women’s own accounts, is treated much the same.

In cases of assault and rape, we have witnessed innumerable instances of how a woman in the eyes of all state and social structures is seen to be lying from the get go: often seen as an irresponsible and a frivolous person, acting too carelessly, falsely accusing someone, “destroying the life of the men”.

In Allegedly, similar treatment is given to the protagonist, played by theatre artist Mallika Taneja, a woman who reports that she was violated, but sixteen years later, “a little too late” according to her friend, Aditee. The scene of the play soon cuts to a group of friends, notably in chorus format, observing the conversation between the journalist and her friend. These group of friends dare to question the journalist’s behaviour and her subtle gaslighting: How is she asking questions not even pertinent to the crime, and how her questions seek to place all the blame on the woman instead of the man.

According to a UN Women report, women and girls feel the safest and free from violence or the fear from violence in safe and inclusive spaces. Women often tend to not report instances of harassment they have faced owing to various factors but ultimately, due to fear. A study published in 2015 finds that in the National Capital Region, 77% of women do not report instances of sexual assault and 59% of women said that they have stopped going out alone altogether, in order to avoid such crimes. Moreover, due to the insensitive behaviour and the constant interrogation by the police about the “clothing” or “whereabouts” of the survivors themselves (a classic case of victim blaming), women are unwilling to come forward. Allegedly deals with a lot of these lingering questions asked by the state actors around sexual assault –

“Is it rape if I don’t feel raped?”

“Can feeling be a fact?”

“What do you want?”

“Is the law the only form of justice?”

“What is justice?”

“How do you feel?”

As women, we all have been asked these questions at different points in our lives.

In June 2020, Justice Krishna S Dixit of the Karnataka High court granted bail to the accused whilst questioning the survivor’s behaviour and finding it “a bit difficult to believe”. He went on to reiterate that her behaviour, that of sleeping, after the incident was “unbecoming” of an Indian woman. Women being expected by none other than the law itself to follow a rulebook their entire lives, even during cases of gendered violence, makes for an ideal condition for patriarchy to flourish and thrive, and for our women to be under constant surveillance.

In conclusion, according to the systems that govern us (our bodies and movements), the onus of the crime almost always lies with the woman, she did something to instigate the man and “how dare she turn the man on and then not expect this to happen?”

In Allegedly, the character played by Mallika and the perpetrator start by having sex consensually. The violation happens when the two are in the shower and all of a sudden, he removes the condom and ejaculates inside her. There are very few pieces of political art, at least in India, where consent, inconsistencies, irregularities and uncomfortable conversations have been so openly discussed. Allegedly, however, is markedly different. As the chorus questions the behaviour and conduct of the woman, and who really is at fault here, we as the audience find ourselves asking questions too- in fact, we need to question laws and semantics around us.

Allegedly, performed in an interactive format, throws questions at us with a 30-second timeframe to answer them – they range from questions about the situation: Is the woman at fault? Or, is she just overreacting because she enjoyed it too, until she didn’t?

Allegedly, performed in an interactive format, throws questions at us with a 30-second timeframe to answer them – they range from questions about the situation: Is the woman at fault? Or, is she just overreacting because she enjoyed it too, until she didn’t?

A question that stood out to me was, “Is the woman a good rape victim?”. I was rather confused at this question, because I wondered (for as long as 20 seconds), what exactly makes a good rape victim? How do we answer a question such as that? How do we differentiate between good and bad rape victims?

Also read: A ‘Good Rape Victim’ Is A Dead One | Analysing Public Sympathy In India

Clearly, Allegedly made me learn, unlearn and relearn consent and boundaries as a young, queer and disabled woman. It made me feel empowered and in that brief while, managed to create a safe space for me – where I could question and challenge my pre-existing beliefs and envision a future of communities of radical care – something that is much needed for survivors.

Personally too, Allegedly‘s approach towards consent spoke to me. As someone who’s been assaulted by a man before, consent is so much more than a yes or a no. It is so much more than black and white. Often, as a woman I felt like I was pressured into saying yes even when I didn’t mean it. Sexual relations can be tricky growing up and I’ve blamed myself needlessly for years. The act of Allegedly was one of an understanding, older friend, someone you can turn to and someone who will make you and many, many other survivors of sexual assault, that they are seen and heard.

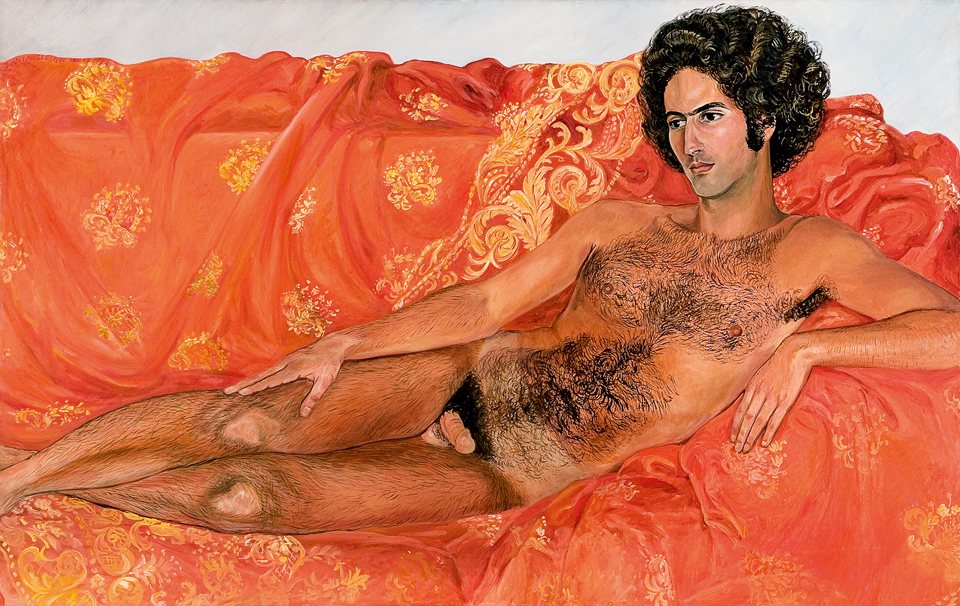

Featured image source: Vooruit.be

About the author(s)

Anusha Misra prefers to be called nu, identifies as a disabled, queer woman. They are a disability justice author, curator and editor. They are the founder and Editor-in-chief of Revival Disability Magazine, a magazine on Disability, Sexuality and Intersectional Ableism. They firmly believe that Intersectionality gives disabled women the emotional skin to survive in the world and that vulnerability should be celebrated. According to them, the revolution would be incomplete without disabled joy and dissent.