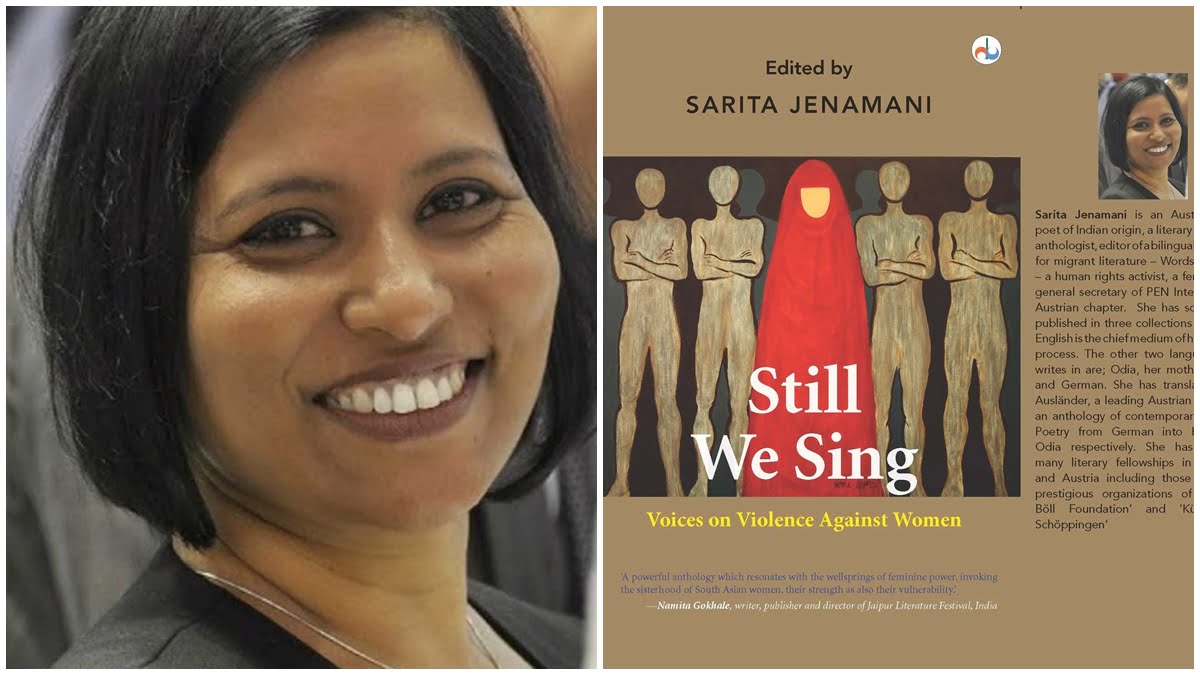

Born in Cuttack, Orissa, Sarita Jenamani studied Economics and Management Studies in India and Austria. She writes in English, Hindi and Odia, which is her mother tongue. With three books of poetry to her credit, she has been published in international literary journals such as the PEN International and several anthologies, many of which were translated into several languages. Jenamani has also translated contemporary Austrian Poetry into Odia. She has been the recipient of many literary fellowships in Germany and Austria, including those from the prestigious organisation of ‘Heinrich Böll Foundation and ‘Künstlerdorf Schöppingen. In 2006, she was awarded the literary prize of Kulturverein Inzing, Austria. Jenamani, who is now the general secretary of Austrian chapter of PEN international, lives and works in Vienna. She is the co-editor and publisher of the bilingual magazine Words and Worlds.

Recently, Sarita Jenamani curated an anthology called Still We Sing by South Asian Women writers on the topic Violence against Women.

Also read: Interview With Dr Manjima Bhattacharjya, The Author Of Intimate City

Heartiest congratulations on the publication and launch of Still We Sing, the anthology of diverse voices on violence against women. Tell us about the book and how did it happen?

Sarita Jenamani: Thank you. In fact, congratulations to all the contributors! They have enriched this anthology with their unique and powerful voices. The whole idea of this book, “Still we Sing: Voices on Violence against Women”, with writings by women from South Asia, emerged out of a symposium organised by PEN Austria where I was asked to present a paper on the literary responses to violence against women in South Asia. While preparing the article, I reflected upon how indifference is a death sentence and how a bystander is also an enabler. I wanted to know what women had to say about the violence against them that was being perpetuated in the name of religion, tradition, or culture. I did not want to go round without addressing the issue at its core. In the process of my research, unfortunately, I could not trace even a single anthology of poetry or prose on this issue. So, I decided to collect and compile a volume of poems written by South Asian women.

Janet Montefiore in her essay Feminist Identity and Poetic tradition says, “The interrogation of received meanings and the creation of new ones are tasks shared by all women, but poetry has a particular role through its ability to conjure language into new significance.” What do you think?

Sarita Jenamani: Since ages, across cultures, women are closer to words than to silence and the medium of poetry has always played an important role in the process of communication in women’s life. Poetry written by women opens up like linen of plenitude and possibility in every cultural scenario. Women write to record their history and as a part of the common legacy of literary history. Female poetic practise forms an important part of women‘s literary history.

Many modern women writers reflect on the issues highlighted by feminism and elaborate female identity in their works. Of course, writers’ movement, their techniques and thematic works are necessary to understand women’s issues and feminine concepts in different situations and stages of their lives. They develop a female framework through figurative languages. Women’s poetry is all about decoding the silence; this is a search for the unspoken. Through the richly woven tapestry of poetry, ornamented by various texts and texture, women express themselves and mould their destinies. Their voices filled with the enormous power of language and individuality.

Women’s poetry is all about decoding the silence; this is a search for the unspoken. Through the richly woven tapestry of poetry, ornamented by various texts and texture, women express themselves and mould their destinies. Their voices filled with the enormous power of language and individuality.

When in your life did you feel the calling to become a poet?

Sarita Jenamani: I was born and brought up in a family where we had a lot of independence and opportunity to flourish, but we had to move within a certain invisible boundary line that we were not allow to cross just like almost all the middle class families in India. Questioning tradition was not something we were supposed to do. In the process of growing up, addressing certain issues was not easy. Poetry has often been taken as a form of resistance and a powerful way to give voice to those who do not have it. So, I adopted poetry as my medium of expression. It was a conscious decision that I took when I was in college.

How have your ideas about the position of women changed over time?

Sarita Jenamani: I have always believed that there is an apt room available for a woman to live more freely than before and without prejudice. After moving to Austria I observed that, though women have achieved equal rights and personal freedom on paper (and when I am saying that, I am talking of all women irrespective of their social class, education level or sexual orientation) they still have a long way to go even in the so called liberated western society. But women are constantly struggling for their betterment. Their lot in South Asia is even worse where it is even more difficult to break away from traditional patriarchy; they are required to make sacrifices as patriarchy inculcates in their minds that only they are responsible to keep the culture and tradition intact, at the cost of their wellbeing and freedom of mind and body. Women have to obey the rules set by patriarchal set-up and in many cases, are not even aware of their exploitation.

As a poet, writer, translator and editor of a bilingual magazine, you not only have voice in the arts and literature but a vantage point too. Do you see sexism in the arts?

Sarita Jenamani: – Well. We may say that women poets have now secured their place in literary history. In the words of Virginia Woolf, they have already found a room of their own. Nevertheless, economic, social and psychological barriers still stand in the way of production of art and literature, especially poetry, by women and in the full acceptance of women artists and writers in the mainstream literary and artistic field. Again, the publishing industry is still a male-dominated area and most of the art and literary establishments are also headed by men.

Still, you find a handful of women in anthologies. Literature written by them within a framework of a male-dominated literary criticism has not been given due recognition in the contemporary literary discourse. Most of the time, the reader remain clueless about the existence of the wonderful women poets who depict their inner and outer world in words. Unfortunately, sexism also prevails in the art world just like in any other field.

In recent years, horrifying incidents such as the December 2012 rape case combined with the #Metoo movement that followed in a few years later, shook the society to the extent that laws were revamped and gender sensitisation was vigorously promoted at various levels. Yet, violence against women continue to manifest in several ways in India, especially on the Internet with body shaming and rape threats as a regular feature. What do you think is missing from our quest of social justice and gender equality?

Sarita Jenamani: The violence to which women are subjected to is not random neither can be defined by specific circumstances alone. It is used as a weapon to punish women for stepping out of the boundaries set by the power structure of patriarchy.

Also read: Interview With Kritika Pandey: 2020 Commonwealth Short Story Prize winner

We do need to change the way our society looks at its women. Indian society is completely plagued by the Devi syndrome, that means if a woman follow the rule set by patriarchy then she is termed as a goddess otherwise she is a fallen woman, says Sarita Jenamani.

It is not that we do not have laws to protect women. However, we do need to change the way our society looks at its women. Indian society is completely plagued by the Devi syndrome, that means if a woman follow the rule set by patriarchy then she is termed as a goddess otherwise she is a fallen woman. Women must stand in solidarity with each other rather than allowing themselves to be pitted against each other and committed to carry the flag of patriarchy. It is not always productive to take the streets with protest march. All change begins at home, in our personal resistance – silently but strongly is a more effective way. Each and every one of us owes it to our posterity.

One narrative that is widely accepted happens to be “women are their own worst enemies.” What do you think about it in relation with women empowerment?

Sarita Jenamani: Society offers just a little power to women and that too only to those who support its value system. There are women who want to enjoy whatever power they can, but often, they tend to overlook the disadvantageous groups. They know it is difficult to resist a system that is well rooted and armed with religion, cultural believes and tradition. Or, in many cases, the system is such that that they are made to feel insecure if they do not uphold patriarchal values in order to survive in the position they are holding, irrespective of their educational, financial background or religious or cultural believes. Before we commit ourselves to be the champions of traditions, we must pause and consider whether this tradition deems every individual as equal?

In your Editor’s Note in Still We Sing, you mention that “this book is not an anthology of feminist poetry.” Rather it is a home to “all women voices rendered silent by the vicious trinity of oppression, denial and victim bashing that has allowed violence against women to escalate to an alarming magnitude.” Where can this collective of feminine voices lead?

Sarita Jenamani: Silence allows predators to rampage through decades unchecked and the omnipresent silencing apparatus of patriarchy devours the voices of victims and turns the women’s subjectivity into mere nothingness. Poets of this anthology position their views in a manner that let the world understand the power of women’s voices. These voices underscore new thematic concerns such as self-respect and their power to overcome the stigma of gender-based violence by questioning the validity of such actions in their own culture and society. These poems raise questions of identity and dignity. They expose misconceptions about women as depicted by the society. These women writers give voice to the voiceless through their poetry.

What advice would you give to young women in our society?

Sarita Jenamani: I can only say that as women they should try to create a more compassionate world. Before positioning themselves as the cheerleaders and torch bearers of certain tradition, culture or religion, they should pause and reflect upon how humane these values are after all. We have a long way to go, and each and every one of us, especially the young women should not forget to stand up for their own and their sisters’ right. Everything great starts at home and with small gestures.

Nalini Priyadarshni is a poet, writer, translator, and educationist though not necessarily in that order who has authored Doppelganger in My House and co-authored Lines Across Oceans. Her writings have appeared in numerous literary journals, podcasts and international anthologies. A nominee for the Best of The Net 2017 she lives in Punjab, India.