Social mobility is defined as the upward or downward movement of one’s socio-economic status within a class system society. This movement can occur intergenerationally or intra-generationally; and since individuals’ socio-economic backgrounds largely determine the privileges and resources accessible to them, social mobility has become a major topic of interest in the field of social sciences.

Darker skinned individuals were characterised with negative stereotypes which promoted stigmatisation and discrimination against them, resulting in the development of structures purposed to keep marginalised individuals at the bottom of the ladder.

Throughout the 20th century, an increase in Latin American and Asian immigration started changing the U.S. racial demographic from mostly Black/White to a more graduated skin color hierarchy. However, along with a changing demographic also came newer forms of institutionalised discrimination, which is why it has become crucial to study non-White immigrants’ experiences with social mobility. In this context, it becomes important to analyse the different experiences darker versus lighter skin toned immigrants have in the U.S. regarding occupational, wealth, and income prospects caused by colorism.

Also read: Can Mere Representation Be The Solution To Problems Like Racism?

To illustrate a clearer picture of the current United States’ racial makeup, I will first discuss the Latin American racial stratification system that has existed since the 1500s colonial period. After the Spaniards colonised Latin America, a hierarchy was set up to secure White people’s position at the top: establishing this power made it easier to exploit Latin American resources. The hierarchy was set up according to skin color, with Spaniards ranked at the top of the chain, followed by Creoles, Mestizos, Indios, and Africanos, in that specific order. Darker skinned individuals were characterised with negative stereotypes which promoted stigmatisation and discrimination against them, resulting in the development of structures purposed to keep marginalised individuals at the bottom of the ladder.

The current racial hierarchy in the United States somewhat resembles that of Latin America due to the massive influx of immigrants coming from all over the world. With this changing demographic also came more complicated systems of discrimination, for instance, discrimination in the job market. Prior research has found that darker skinned Americans in general have lower rates of education completion, lower pay, and jobs with lower prestige. A study by Dr. Painter and colleagues’ specifically found that darker skinned immigrants tend to have lesser wealth and own fewer assets. Compared to darker skinned immigrants, lighter skinned immigrants tend to earn 17% more in salary.

One particularly interesting study by Dr. Han found that darker skinned immigrants face greater barriers towards upward mobility than their lighter skinned counterparts. Upward mobility in the context of social mobility means shifting to a higher class, and the author discovered, upon research, that while both darker and lighter skinned immigrants get to experience upward mobility, darker skinned individuals experience a significantly more gradual upward mobility. In addition to a slow upward mobility, darker skinned immigrants in general undergo a steeper downward mobility before right before their upward mobility, which contrasts with lighter skinned immigrants whose downward mobility patterns show to be less steep.

This particular study goes against the assimilation theory, which claims that immigrants’ external features will not act as a barrier towards upward mobility as long as they assimilate themselves within the U.S. culture. Immigrants’ home cultures are usually seen as disadvantages, therefore, immigrants are heavily pressured to acculturate and leave their old identities behind. The problem with this theory is that it attributes downward mobility to individuals’ characters, as if their struggles are purely a result of their “bad habits” and inability to blend in. The assimilation theory fails to acknowledge that many privileged people tend to hold implicit racism, which makes them act biasedly towards whom they hire and how much they offer to pay them. As several research studies have found, physical features do play at least some part in acting as barriers against the access to many privileges.

Furthermore, the assimilation theory also minimises the extent to which people’s socio-economic backgrounds shape their identities. According to Dr. Ainslie’s work, an individual’s class standing influences a wide range of traits such as their taste in music, food, fashion, and most importantly, their self-esteem. Ainslie’s assertion about individuals’ social class impacting self-image, along with Han’s research about darker-skinned immigrants and downward mobility imply that darker-skinned individuals experiencing downward mobility may start viewing themselves as unskilled or untalented; this in turn, further perpetuates systemic racism because these individuals now feel that they deserve to be in their unfortunate positions.

Even though explicit racism may not be as common in the U.S. as it was before, implicit racism is still integrated into the major institutions and is continuously perpetuated by events such as the differential treatment of lighter versus darker skinned individuals.

Also read: Meghan Markle’s Interview: The Insidious, Pervasive Racism Of The British Monarch

Institutionalised colorism came with the onset of colonialism during the 16th century and has constantly served to be a major problem throughout the world. The consequences of colorism has resulted in the development of several problematic modern day phenomena such as racism, discrimination, stigmatisation, and prejudice. Even though explicit racism may not be as common in the U.S. as it was before, implicit racism is still integrated into the major institutions and is continuously perpetuated by events such as the differential treatment of lighter versus darker skinned individuals. Therefore, it’s important that we study issues of race and colorism in intersection to other flawed systems in our society such as our unequal class system, as it will give us a deeper understanding of the problems that are devastating marginalised communities everyday, eventually leading to the construction of better, more effective solutions to help these improve our communities.

References

Ainslie R. C. (2009). Social class and its reproduction in immigrants’ construction of self. Psychoanalysis, Culture & Society, 14(3), 213-224. https://doi.org/10.1057/pcs.2009.13

Han, J. (2020). Does skin tone matter? Immigrant mobility in the U.S. labor market. Demography, 57(2), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-020-00867-7

Montalvo, F. F., & Codina, G. E. (2001). Skin color and Latinos in the United States. Ethnicities, 1(3), 321-341. https://doi.org/10.1177/146879680100100303

Painter, M. A., Holmes, M. D., & Bateman, J. (2015). Skin tone, race/ethnicity, and wealth inequality among new immigrants. Social Forces, 94(3), 1153-1185. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sov094

Zhou, M. (1997). Growing up American: the challenge confronting immigrant children and children of immigrants. Annual Review of Sociology, 23(1), 63-95. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.23.1.63

Madiha is an intersectional feminist who wants to write to spread awareness of marginalised issues.

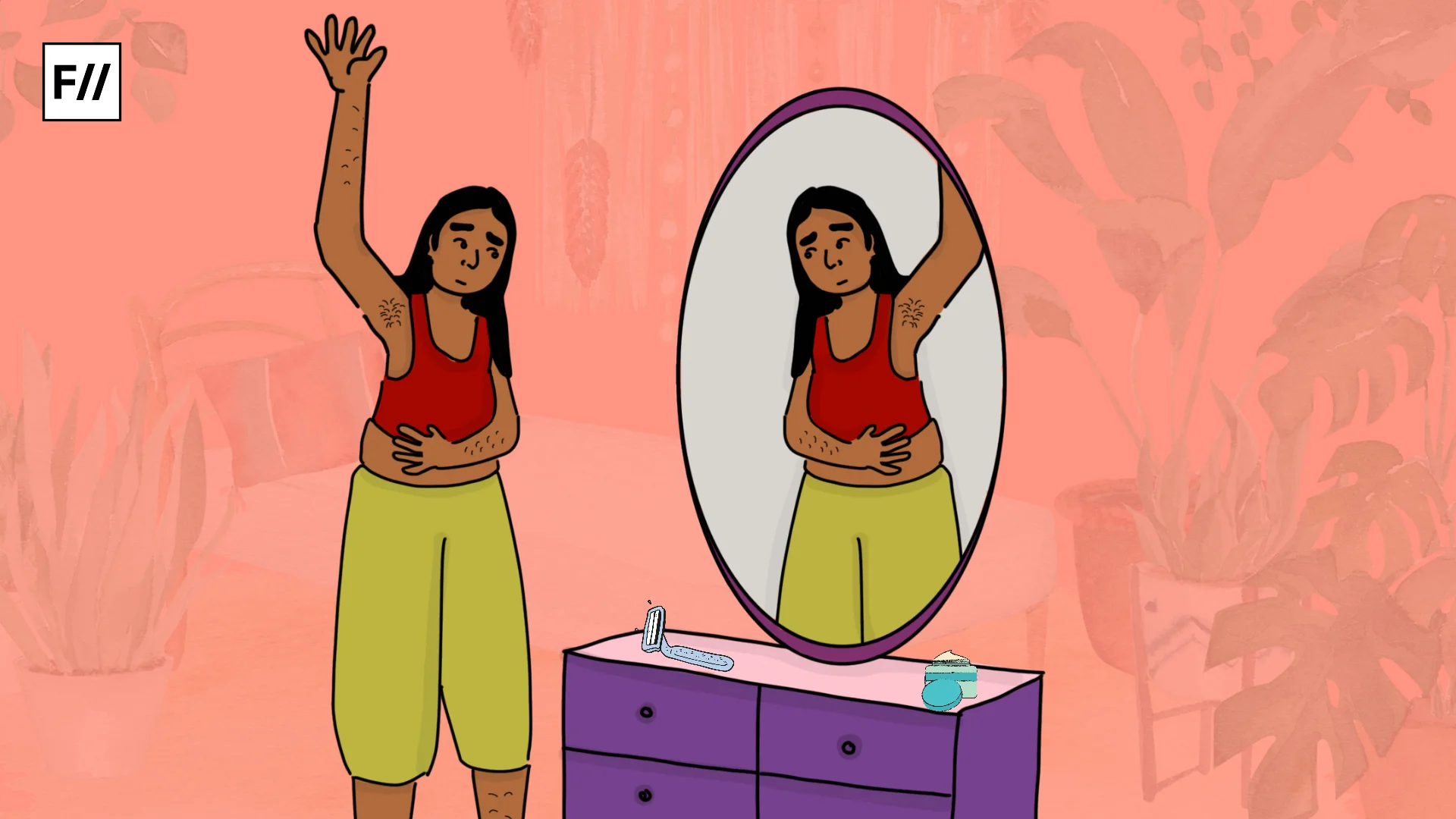

Featured image source: Africans.us