Posted by Prachi Sharma

Earlier May, as India woke up to the results of the Bengal Assembly elections, what followed right after were the visuals of post-poll conflict and violence in the State. A lot of that turned out to be fake news, reproduction of old photos and videos while only some information was found to be true. Soon, people on the Internet could be seen indulging in arguments, hurling misogynistic abuses (verbal violence on women), as to assert their own idea of ‘truth’. The question is: how does the internet, dominated by the toxic-masculine ethos of power, revenge and war, talk about women? Their use of language, especially during conflict, demands an interrogation of the way in which women are treated as pawns in the battle between two sides even today.

The question is: how does the internet, dominated by the toxic-masculine ethos of power, revenge and war, talk about women? Their use of language, especially during conflict, demands an interrogation of the way in which women are treated as pawns in the battle between two sides even today.

The fake news of men from TMC sexually assaulting two women polling agents from BJP during the post-election violence in Bengal had been making rounds on social media. Someone on the Internet said that it is political bias which is stopping people (“even feminists”) from at least acknowledging these cases of brutal sexual assault as the possible ‘truth’. Someone else argued that these are the losing party’s propaganda tactics. Many let the matter die in graves of communal fervour.

However, what remained to be closely examined within this discourse is the normalised attitude towards women’s sexuality. Specially in times of conflict, a woman’s experience of violence extends to her body in a different way than it does for a man. India’s social fabric is such that it renders women from different socio-cultural backgrounds as victims of violence in different ways while what rests behind this gendered nature of violence is man’s thirst for power.

Also read: Sudarshana’s Escape & Veera’s Return: Two Stories Of Partition’s Abducted Women

It would be helpful to go back into the past and see how it manifests itself into the present. Also, is there a pattern in how the male dominated narrative continues to see women? India is a communally tense country. This all started way back in and around 1947: when Pakistan and India attained independence but at the cost of Partition.

From Saadat Hasan Manto’s short stories like ‘Thanda Gosht’ and ‘Khol Do’ to Amrita Pritam’s 1950 novel Pinjar, many writers recorded the horrific event that the Partition was, particularly for women. For a long time though, feminist researchers complained of a dearth of first-hand accounts of women during the partition. History, like most other disciplines, had also failed women. Written and controlled by men, women figured only as numbers and typecasts under the male gaze. It was largely the history of men, full of them just like the museums of historical significance. It was only in the year 1998, that we finally had two seminal works which not only dealt with the human aspect of partition but also with personal narratives from different social standpoints – Urvashi Butalia’s The Other Side of Silence and Borders and Boundaries by Ritu Menon and Kamla Bhasin.

Butalia shares in her book how she had first started with the intention of interviewing partition survivors. Only later did she think about how in all the families she had met, none of the women said anything. Whenever she would ask questions or initiate a dialogue, men would be the first to speak. Women would either silently listen or not even be around. Women who didn’t survive had also become absences in their families. There would be no mention of what happened to them. Finally, Butalia found all these women in silences, in gaps between utterances. This reminds one of the lines from Kamleshwar’s story ‘Kitne Pakistan?’: “Women never forget anything. They only pretend to forget. Otherwise it would be difficult for them to go on living.”

Butalia and the Menon-Bhasin duo went on to look for these very voices. In the process, they uncovered the truth about men’s treatment of women’s lives. Women were raped and abducted by men as a symbol of their power over the other community. The whole ordeal was a tool to subject the ‘other’ through humiliation – ‘inability’ to protect ‘their’ women. The notions of “honour” and “morality” permeated not only the mistreatment that women were subjected to but also the apparent ‘recovery’ of abducted women from the other country irrespective of whether or not they wanted to be ‘recovered’. Communities would even be ready to kill the women of their own, lest they be ‘dishonoured’ by the other. The words of major figures were furnished by the rhetoric of power.

Describing how the inability of one country to recover ‘as many’ women as the other was seen as the sign of its ‘weakness’, Butalia quotes Professor Shibban Lal Saxena who went on to project the Hindu moral code of conduct on the situation by saying that “for the sake of one woman who was taken away by Ravana the whole nation took up arms and went to war” — A classic example of women put down as mere subjects for men to wage their wars on.

Menon and Bhasin describe how when the countries were negotiating a plan to rescue abducted women, some people went as far as to say that only an “exchange” of women be considered, “what they give is what they will get” – like commodities. An officer of the Indian Civil Services, KL Punjabi felt that “we had not recovered enough women in proportion to the money spent on this work.” In India, there was a huge problem of families unwilling to accept women now that they had been “defiled” by Muslims such that the Ministry of Relief and Rehabilitation had to bring out ‘educational’ pamphlets which said: “just as a flowing stream purifies itself and is washed clean of all pollutants, so a menstruating woman is purified after her periods.” It is impossible to not see the sheer manipulation of the process by assertion of masculinity and false patriarchal ideas.

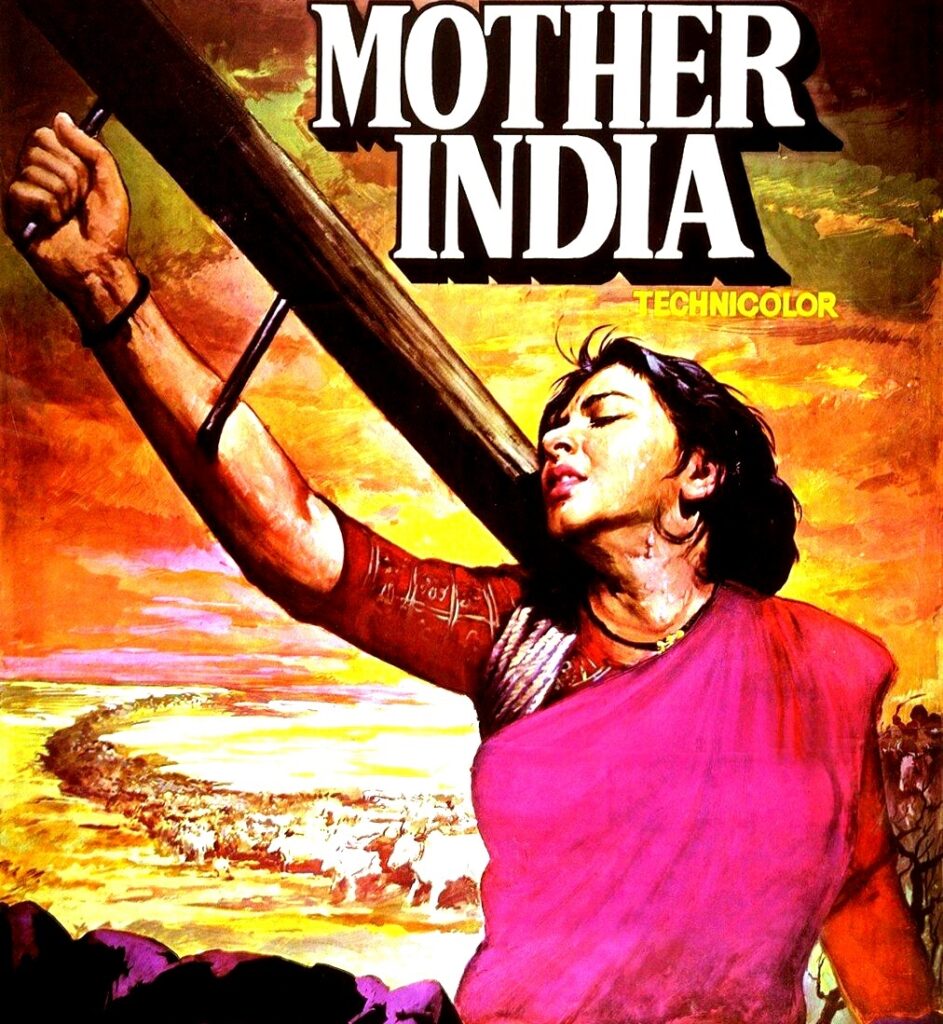

As the country came to be seen in the image of “Mother India”, the assault on women by the other became equivalent to the motherland being violated by the foreigner against the man’s effort to ‘protect’ it. Now, Indian feminists reject these images and metaphors. It is difficult to not see a parallel between the male dominated narrative around women’s sexuality during the partition and the treatment of the cases of sexual assault today under the male gaze. Menon and Bhasin elucidate how over the main objective of the program, what became important was “to identify the women as either Hindu or Muslim” for the matter was now about countries’ prestige. This brings us back to the recent event in Bengal which, although isn’t the only one of this nature, but is worth pointing out – how to infuse communal tension and play a game of party politics, even “fake news” is written over women’s bodies and sexuality.

The internet also speaks the male-centric language of aggression. It operates through people irrespective of their gender but when discussing sexual violence on women, it becomes important to identify ‘who’ is saying along with ‘what’ they are saying. People on the internet, especially men, who ordinarily wouldn’t extend solidarity and support for women survivors of sexual assault and would even enable rape culture through their speech, suddenly want to talk about it now that it can be given a communal colour. Women as ‘beings’ are again invisiblised in this discourse as our spaces are hijacked by the male gaze and masculine struggle for power. [Trigger Warning: Abuse] Reading a random man’s comment on a post: “Now these BJP hating feminists want an evidence of the rape (probably on a xxx site)” is a major trigger. One can only imagine how a young girl on the internet feels coming across such a statement on a daily basis. Internet has ceased to be a safe space for women.

It is crucial, however, to separate this aggressive patriarchal communalisation of women’s sexual assault from the very necessary acknowledgement of identities across religious, caste and other socio-cultural lines. Since the assertion of Hindu-Muslim conflict in the case of sexual assault fuels the communal agendas of the political elite, they amplify it. Whereas in the Hathras case of September 2020, the acknowledgement of caste identities went against the agendas of the dominant caste elites, there was an effort to silence it. Some on the Internet spoke on the lines of: “Why does the victim’s caste matter?”

Also read: The Hypermasculine Post-Poll Violence That Took Over West Bengal After Elections

In her ground-breaking essay ‘The Orders Were To Rape You’, Meena Kandasamy gives a picture of the Tamil Eelam struggle and recounts her journey to Malaysia and Indonesia to talk to women who were the survivors of sexual violence by the military. She asserts: “Women raped as a weapon of war are potent tools for political mobilisation and grandstanding oratory, but in everyday life, they are viewed with derision, suspicion, shame”. While one of the survivors is narrating her story to Kandasamy, she tells her about the answer she received upon asking her rapists why they do this to her, “They wanted the wombs of our women to bear their children”.

This reeks of the masculine ideas of power while sexual violence becomes their tool for it. Upon threatening to complain to the superiors, she was told, “These are their orders”. Here, the woman is further oppressed with respect to the man because of her position in the hierarchy.

In Hansda Sowendra Shekhar’s collection of short stories ‘The Adivasi Will Not Dance’, one comes across the narratives of Santhal women and their exploitation by Diku men – the outsiders and the privileged. One story named “Getting Even” ends with the description of brutalities that so many girls would have had to go through “just for warring parties to get even with each other”.

Women’s spaces have continued to be hijacked by male dominated narratives. Unfortunately, this continues to happen on the Internet every time any such atrocity comes to light. Men’s language on the internet today echoes the language of those from the partition.

Sexual violence on women, has in the past and today, continues to be used as a tool in conflict and to wage wars. Women’s spaces have continued to be hijacked by male dominated narratives. Unfortunately, this continues to happen on the Internet every time any such atrocity comes to light. Men’s language on the internet today echoes the language of those from the partition. Since this generation ‘lives’ on these online spaces now, such a culture cannot be ignored. Women need to continue reclaiming their spaces and discourses and become the agents of their own lives.

References

Butalia, Urvashi. The Other Side of Silence Voices from the Partition of India. Penguin Books, 2014.

Kamleshwar, et al. “How Many Pakistans?” Manoa, vol. 19, no. 1, 2007, pp. 193–206. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4230534.

Kandasamy, Meena. The orders were to rape you. Navayana, 2020.

Menon, Ritu, and Kamla Bhasin. Borders & Boundaries: Women in India’s Partition. Kali for Women, 1998.

Sekhar, Hansda Sowvendra. The Adivasi Will Not Dance. Speaking Tiger, 2015.

Prachi is a postgraduate student of Literature at University of Delhi. How the language of ordinary discourse both has an impact on and is impacted by society is an area which interests her. She wants to study the expansion of this phenomenon on the internet, specially as a space for the marginalised. Her recent essay on social media as a democratic and burgeoning place for literature has been published in a book called ‘Indian Popular Fiction: New Genres, Novel Spaces’ which is available on Amazon. She can be found ranting and occasionally sharing her writing/art/reads on Instagram.

Featured image source: Deccan Herald

About the author(s)

Guest Writers are writers who occasionally write on FII.