One of the ways in which gender equality is reflected within marriages is through the equal distribution of domestic chores among the partners. In the context of the changing society, more women are taking up careers and this has considerably contributed to the dismantling of patriarchy’s sacrosanct model of the “male breadwinner” household.

However, women still continue continue to disproportionately bear the burden of performing household activities even though their roles have changed from the traditional moulds of housekeeping and care giving. This simply means to say that “choice” for women in terms of working and earning comes with the cost of continuing to also manage the household in heterosexual partnerships. Their foray outside the domestic space is thus contingent on overcompensation, including performance of activities that enable adherence to traditional, and heteronormative gender roles.

By viewing “empowerment” in a unilinear fashion, that simply forges a link between financial stability and women’s empowerment, we “disempower” women by discarding underlying inequalities. We fail to acknowledge the socio-cultural conditioning that is an invisible force curtailing true empowerment when we continue to romanticise the performance of domestic chores by women

Seamlessly interwoven with the performance of domestic tasks, are notions of caregiving and nurturance, both of which constitute socio-cultural connotations of “wifely” and/or “motherly” duties. This discourse reinforces, perpetuates, and normalizes women shouldering a larger portion of domestic work, compared to their male counterparts. Here are five ways in which the domestic work assigned to women are romanticised and consequently normalised as work exclusively meant to be done by them:

1. Women are inherent nurturers

The debate on dismantling the gendered norm of women taking care of the domestic realm, has also brought in debates about deconstructing the concept of household work as a “life skill”, and not a “gender role”. However, for men who perform domestic tasks, the aspect of “functionality” is at the forefront of their performance. For women on the other hand, socio-cultural and historical accounts of gendered expectations have cultivated the image of a caregiver, the acme of nurturance, for whom the motivation to perform domestic work primarily stems from caregiving, and valuing others emotional needs and well-being over her own.

2. Only Maa can make such delicious food

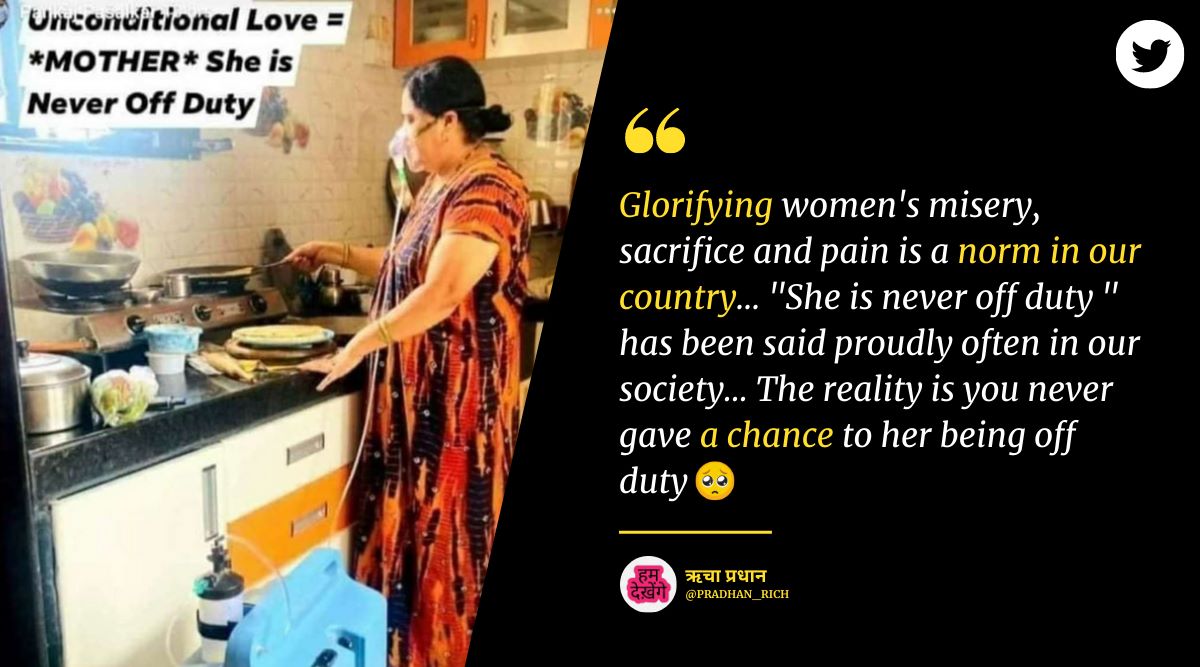

Women cooking for their children is an act that has been timelessly peddled as “pyaar se banaya hua khana”, “maa ke saath ka khana”. These are not mere statements but reinforcements of gendered ideals that locate domestic work at the center of wifely and/or motherly duties. The interlacing of domestic labour with sentimental value, is a link forged only between women and domestic work, which is indicative of the gendered notions of the task. Let us also recall the photograph of a woman cooking for the family with an oxygen concentrator attached to her being glorified as “mother’s unconditional love“.

3. Women are happy to give, their patience is their strength

Women are relentlessly portrayed as deriving happiness and fulfilled emotional needs through performing work for the family members. To lace a woman’s self worth to how well she performs domestic caregiving work, is to further romanticize the notion of emotional labor. This narrative continues to erase her worth as an autonomous individual to someone who only exists in relation to others. The sexist stereotype that women must smile more, is also rooted in this idea. A woman must be constantly beaming even while slogging in the house with no help.

Displaying disappointment or even frowning while performing these tasks itself makes her the recipient of harsh criticism not only by men but also by women, as this goes against the social construct of the sacrificing, patient home maker, happiest only when her family approves of her labour.

Also read: Are Mothers Machines? A Review Of Interrogating Motherhood

4. Women are multi-tasking super humans

Women who choose to work are not easily encouraged, and motivated to do the same. Their value and dignity continues to be tied to their role as a mother or a wife. No matter how much they excel at work, at the end their value and respect is determined through how well they perform gendered domestic roles.

Additionally, for most women, being able to work comes with the condition of continuing to perform domestic tasks and subscribing to the patriarchal ideals of wifehood and motherhood. Owing to this, women overcompensate by not only managing their career, but by overworking in the house. This is referred to as “corrective” work, wherein, to “correct” their “deviation” from gendered expectations, women overcompensate by conforming to traditional gender roles. This predicament is romanticised and normalised by the society by handing overworked women trophies for being “multi-taskers” and “super women“.

Image: Forbes

5. A woman is the glue that holds a family together

Domestic work being the prerequisite to be a “good” mother or wife, women who have a career suffer from immense guilt for not not putting enough effort at home while their male counterparts face no such problems. Social conditioning is at the core of this guilt followed by being reprimanded for having a career. Subsequently, issues in the household are conveniently blamed on the woman of the household being absent or simply not being present full time. The woman being the “glue” that holds the family together, her “choice” to do something for herself in terms of a career, is baffling to many firstly, because she chose herself, and secondly, because she has “failed” the family. This attitude of the woman being the one who keeps the family together is another trope to ensure women stay slaves to lop-sided family structures.

Also read: Can An Unequal Marriage Be The Foundation Of A Family?

Caregiving has always been associated with women and it carries with it the reinforcement of gendered ideals. Nurses, teachers, nannies, and domestic help are careers most often chosen women, as women are believed to be best suited for these profiles, owing to the widespread misbelief that providing care and nurturance are “biological givens” for women. So, while career opportunities for women are sporadic, they are further limited and filtered through the “womanly” lens. In this vein, motherhood is also a glorified gendered ideal, and men wanting to be stay at home partners is frowned upon, not only because this goes against the male breadwinner heteronormative model, but also because men are assigned to be emotionless and thus, duties in the domestic realm performed by men may mar the prestige of the “ideal” family.

Love, nurturance, caregiving, through acts of service, can be viewed in a gender neutral fashion as “love” and “care” and not necessarily “womanly”, since the it comes with massive baggage, which women have timelessly shouldered

Pigeon holed into patriarchy’s expectations of gender roles, the idea of “self-care” for women also has its roots in feminist movements. The crux of the concept is in valuing one’s own emotional and physical needs. To be “selfish” and choose oneself then, was a radical move that upended the dominant narrative of women relentlessly and yieldingly caring for the family. With the burgeoning cosmetic industry, patriarchal ideals of beauty, and the iron hold of capitalism, “self-care” is now reduced to marketing strategies attempting to sell cosmetics and reducing caring for oneself to “good skin”. While women subscribe to the notion of self care in this reductive fashion, they still succumb to ideals of the “perfect” wife or mother, who is the epitome of sacrifice.

By viewing “empowerment” in a unilinear fashion, that simply forges a link between financial stability and women’s empowerment, we “disempower” women by discarding underlying inequalities. We fail to acknowledge the socio-cultural conditioning that is an invisible force curtailing true empowerment when we continue to romanticise the performance of domestic chores by women. It is high time we divorce domestic work from notions of motherhood and wifely duties, and view the same through a functional lens as we readily do in the case of men. Women are not seamless multi taskers, but human beings who are forced to do more work to be given respect and acceptance.

Love, nurturance, caregiving, through acts of service, can be viewed in a gender neutral fashion as “love” and “care” and not necessarily “womanly”, since the it comes with massive baggage, which women have timelessly shouldered.

About the author(s)

Shaniya Karkada is a Postgraduate student of Sociology at Christ University. She believes in learning something new, no matter how small, everyday. She has many interests that constantly change, but the one that has remained is exploring Gender Studies.