Firaaq (2008), a film by Nandita Das, is an important film that bears testimony to the horrors of the 2002 Gujarat riots. Through its intricate explorations of interpersonal relationships, set in the aftermath of the riot, it conveys more truth than one can find in the dissimulated facts portrayed by government records and censored media.

In February 2020, when Delhi faced the brutal attack against Muslims by Hindutva fanatics, one’s mind got post-traumatic flashes of the 2002 Gujarat riot against Muslims, that killed more than 2000 people, committed hundreds of rapes and destroyed innumerable Muslim homes by arson attacks. In the light of this, it becomes important to read the cultural products of this time to get a deeper insight into the horrors of socio-political oppression.

Firaaq is the story of one day in the life of a few characters, in the aftermath of the Gujarat riots and how they emotionally and psychologically process the trauma of the riot.

The film opens with the shot of two men digging mass graves for the incessant influx of corpses of Muslim victims of the riot and the debilitating pain and anger that they feel, setting the context of the film.

Muneera and her husband Hanif, played by Shahana Goswami and Nawazuddin Siddiqui are introduced, who had to flee their home during the riot. When they return, they discover that their home had been burnt down to its skeletal remains. Despite their shock and helplessness, Muneera rushes to check her small container of savings, money that she had set aside without her husband’s knowledge. Once she tells Hanif that all the money is gone, Hanif lashes out at her. Literary scholar and feminist Gayatri Spivak had spoken about the theory of double suppression, where colonised women faced a two-tiered patriarchy, once by the men in her personal life, and then by the political oppressor. Here, Muneera is thus a survivor of this double oppression, once as a wife and then once again by the Hindutva oppressors who would either kill her, rape her or burn her house down.

Das then introduces Arati (Deepti Naval), the docile, abused wife of the Hindu fanatic, Sanjay (Paresh Rawal). In the conversations between Sanjay and his brother Deven, and in the way Sanjay treats his wife, it is proved that religious fanaticism always goes hand-in-hand with misogyny. Right-wing oppressive philosophy bases its roots in patriarchy which makes its followers intrinsically consider women to be voiceless beings that can be torched down like houses. Hence, Sanjay does not hesitate to slap Arati and Deven does not feel any remorse while admitting that he along with a few other Hindu men gang raped a Muslim woman during the riot. Even when Sanjay’s scooter collides with a car driven by a woman, despite the accident being caused by his own mistake, his first reaction was that such events are bound to happen if women are allowed to drive. So through a journey of patriarchy, beginning from casual sexism against women drivers, to inflicting domestic violence on the wife, to raping women of oppressed communities, the misogynistic nature of Hindutva is revealed.

In Arati, the conscience of the nation is represented. Arati suffers from post-riot delusions where she constantly hears a knock at the door and has traumatic memories of a Muslim women begging to be let in. Fearing her husband’s brutal reign in the house, she had refused refuge to the woman, only to hear screams from her dying moments soon after, at the hands of a rabid Hindu mob. As Arati cannot come to terms with this crime that she became complicit in, her conscience gnaws at her soul and she gives in to moments of self-harm, as repentance. Perhaps the most heart-wrenching moments in the film lies in the scenes between Arati and Mohsin, a little Muslim boy orphaned by the riots, played by Mohammad Samad. As Arati finds him loitering aimlessly and brings him home for a while, Mohsin gives her a child’s account of the riot. He says:

“There were so many of them. They were all shouting, they burnt my mother and also my brother. They even killed my sister, my uncle and my aunt. Some even came with swords. They stripped my aunt naked and killed her but they did not take the clothes of the men off. I was hiding inside a garbage bin.”

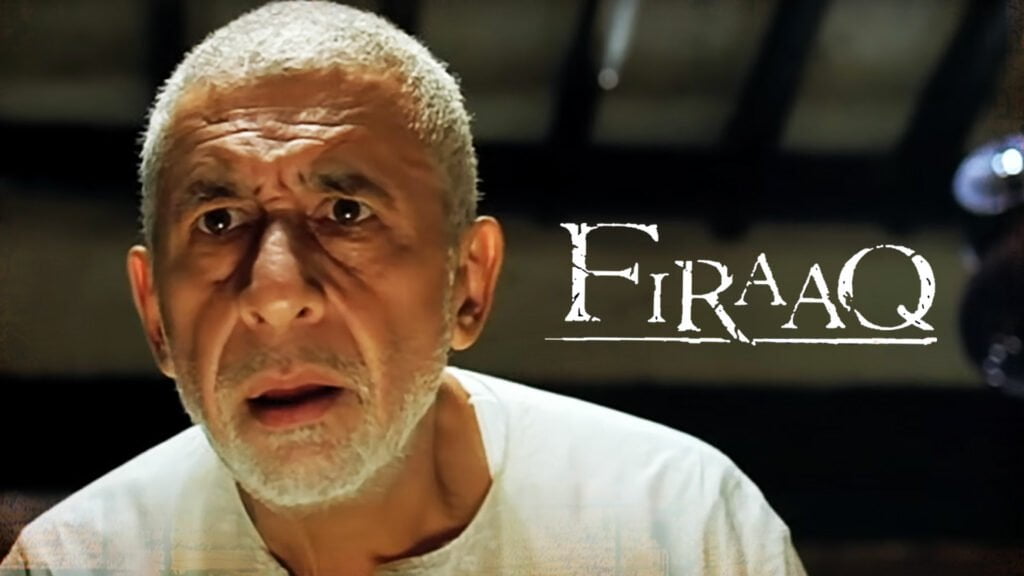

While Mohsin represents the agony that the riot left behind, the blissful and utopian glory of peaceful coexistence between communities is shown through the old Khan Saheb, a locally renowned classical singer, played by Naseeruddin Shah. For a major part of the film, Khan Saheb is unaware of the riot as he is old and barely leaves the home, and his home was spared in the riots. But when he discovers one day that the shrine dedicated to the Sufi saint, Wali Gujrati, which he prayed at, was demolished by Hindu goons, his heart breaks. It is symbolic as Khan Saheb’s utopian dream gives way to a world of Mohsin’s terror.

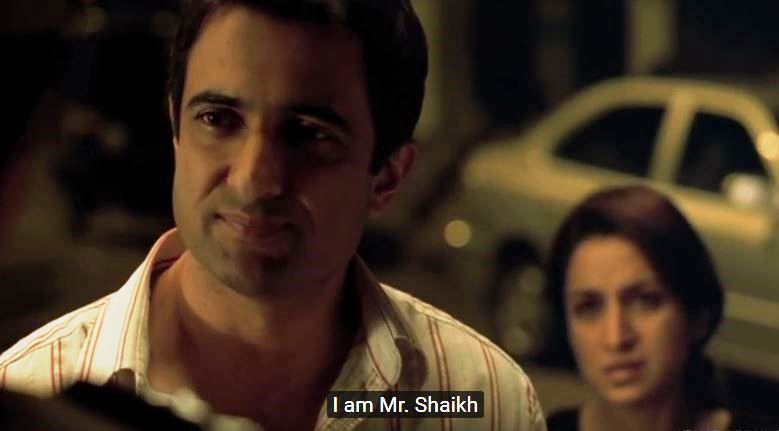

Das explores the national debate on minority oppression through the life of Sameer Arshad Sheikh (Sanjay Suri) and Anuradha Desai (Tisca Chopra), an upper middle-class interreligious couple based in Gujarat, whose lives were spared but their store was attacked and looted. Sameer and Anuradha visit their friends, a Hindu couple, Rajat and Ketki, who abide by the there-are-two-sides-to-the-coin theory. Each time Anuradha or Sameer pointed out what Sameer was facing as a Muslim, Ketki responded by saying that Hindus suffer too, turning a blind eye to an obviously Islamophobic attack.

Even in February 2020, when Delhi was burning and Muslims were being killed, the citizens of the country continued to pretend that the violence was both-sided and that Muslims must have instigated it, almost as if they were justifying Hindutva mob violence. The same has been observed each time Muslims were lynched, where citizens debated whether the lynching was justified by testing if the meat being carried by the Muslim man killed was beef or mutton. In the light of these circumstances, it is commendable that Das critiqued how the supposedly neutral Hindu Indian becomes complicit in the crime by refusing to acknowledge that there is a misbalance in power. It is almost ironic that the solution that Sameer’s friend has is, ‘Can we please change the topic?’

Throughout the film, Das emphasises how only a Hindu upper caste identity could save Muslims from being attacked. Jyoti, Muneera’s friend, sticks a bindi on Muneera’s forehead to pass her off as a Hindu, at a Hindu wedding ceremony. Arati, while watching the news, sees an account of a Muslim survivor who says that while the Hindu mob raped every salwar-clad Muslim woman, she was spared because she was wearing a saree and was mistaken as a Hindu. In a scene later, Arati is almost hopeful that the little boy Mohsin’s mother would be alive because he had mentioned that his mother wore only sarees. Sameer had to conceal his surname and use a Hindu surname so as to escape public disdain.

India is trying to introduce the Uniform Civil Code, where all citizens will come under a uniform code of law and Personal Laws will be done away with. A film like Firaaq makes you realise that the State that has inflicted such violence against minority communities cannot be trusted to form a unified code that will ensure safety and respect for minorities. Minorities will remain victims of majoritarian violence, in this case, Brahminical Hindu fundamentalism, and women in minority communities will continue to be doubly oppressed by the misogynistic laws of their religious community and by the misogyny of the right-wing State.

Also read: Film Review: Kakasparsha—A Casteist Tragedy Of ‘Love’

In a world of growing right-wing fanaticism, one can only hope that films like Firaaq will be revived and re-watched, to instill a sense of empathy and educate the nation on the horrors of state-sponsored hate.

Anwesha is a media professional who loves to create and curate content and is currently working in the world of advertising. Along with this day job, she is also pursuing an M.Phil. in Women’s Studies from Jadavpur University. Anwesha spends her time reading books, swiping through social media and watching films and web shows, in an attempt to understand how popular culture portrays intersectional feminism. Follow her on Instagram and Facebook.

All images via the film Firaaq