Anybody white could take your whole self for anything that came to mind. Not just work, kill, or maim you, but dirty you. Dirty you so bad you couldn’t like yourself anymore.

Some things go. Some things just stay. I used to think it was my rememory….What I remember is a picture floating around out there outside my head. I mean, even if I don’t think it, even if die, the picture of what I did, or knew, or saw is still out there. Right in the place where it happened.

Beloved, Toni Morrison

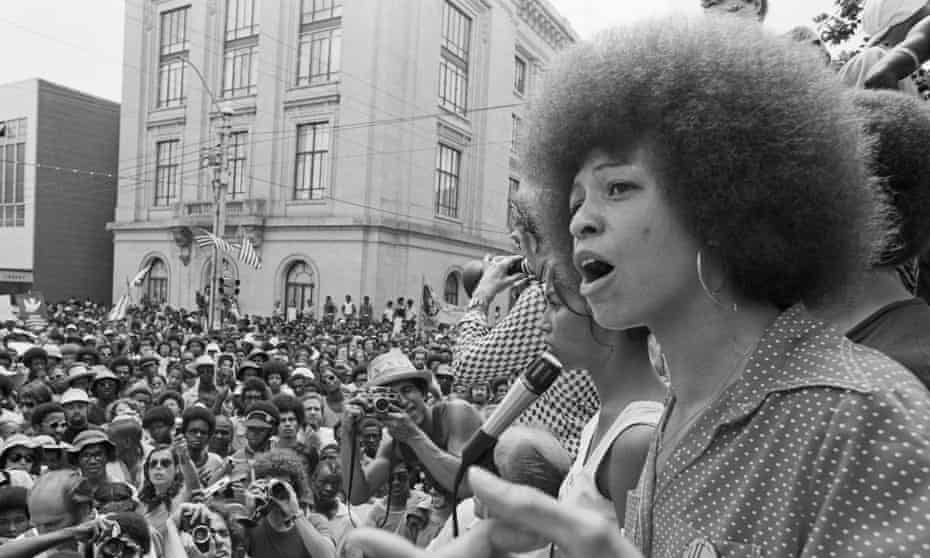

Throughout her academic career, African-American educator, activist, philosopher and author Angela Yvonne Davis has challenged the mainstream discourse. Her contribution lies in the analysis of culture, gender, capital, and race. Her works have greatly influenced much of the theory and praxis in the fields of democratic theory, anti-racist feminism, critical studies and political struggles. Philosopher and journalist Antonio Gramsci, in his conceptualization of intellectuals identifies Organic Intellectual as the one who emerges from a particular social class and “gives his class homogeneity and awareness of its own function, in the economic field and on the social and political levels.” Angela Davis can be understood as an organic intellectual, who had consciousness about her racial and gender identity which inspired her to emerge as a revolutionary political activist in the 1960s-70s. Her activism and counter-hegemonic role in civil society has greatly influenced her theoretical underpinning and writing.

Women, Race and Class (1981) authored by Angela Davis is a collection of 13 essays that chart the history of the struggle for equal rights for women, specifically Black women and working-class women in America. The chapters are arranged chronologically in a manner where Davis has deconstructed the historiography of Black Women from the period of abolitionism to the time when the book was written. The chapters document history and at the same time deal with specific themes involving an intersectional analysis that had not been done before. The major themes that emerge are the points of differences and commonalities in the Suffrage Movement and other women’s rights campaigns, what it particularly meant for the Black population as a whole as well as Black women and working-class women in particular.

The primary contribution of Angela Davis lies in highlighting that power operates from multiple points and is diffused in a network of relations. It is important to remember that gender is just one social relation in the vast matrix of social relations (such as race, class, ethnicity, caste and so on)

Angela Davis further points out how Black women and working-class women have been excluded from women’s movements led by White women and how women from these historically marginalized groups have articulated their issues and resisted hegemonic structures to fight for their rights.

The primary contribution of Angela Davis lies in highlighting that power operates from multiple points and is diffused in a network of relations. It is important to remember that gender is just one social relation in the vast matrix of social relations (such as race, class, ethnicity, caste and so on). She elaborates on this by giving instances from the women’s suffrage movement, where some White women fighting for the rights of women still indulged in racist and classist discrimination. In their activism, they established a social hierarchy tuned to suit their own selfish needs which proved detrimental to the struggle for rights by both Black men and women.

Also read: Watch: Angela Davis’ Lecture On Black And Dalit Lives In Mumbai

In the Indian context, Angela Davis’s interpretations of the struggle of Black women to make their voices heard and carve a subject position resonates with the struggles of Dalit women. For the longest time, the feminist movement in India was dominated by Savarna women, thereby ignoring the role caste played in oppression of Dalit women

Angela Davis also discusses how Black female labour was dehumanized during the period of slavery and was under capitalist formation. By using a Marxist framework of analysis, she points out how capitalism thrives by multiplying the existing conditions of exploitation. As Davis words it, “this subjection of Black female bodies takes place in the form of institutionalized sexual abuse that includes the domestic sphere of unpaid household labour, the market sphere of domestic wage-labour, sterilization campaigns and reproductive rights, lynchings and rape“.

What she then successfully signals towards is the racialized nature of sexual division of labour which in itself is a form of gender oppression under capitalism. The chapters ‘Rape, racism and the myth of the black rapist’ and ‘Racism, birth control and reproductive rights’ from her book are specifically relevant in the present times as they unravel the racist perceptions constructed around Black bodies.

Image: WBUR

In the Indian context, Angela Davis’s interpretations of the struggle of Black women to make their voices heard and carve a subject position resonates with the struggles of Dalit women. For the longest time, the feminist movement in India was dominated by Savarna women, thereby ignoring the role caste played in oppression of Dalit women. Therefore, in the wake of the Mandal agitations when the question of caste became political and actively came up in feminist debates, Dalit women identified caste as the source of their oppression and separated themselves from the Savarna feminist discourse.

Also read: Book Review | Mapping Dalit Feminism: Towards an Intersectional Standpoint By Anandita Pan

Dalit feminists have often articulated how certain kinds of violence like naked parading, dismemberment, pulling out of teeth, tongue, nails, and violence including murder after proclaiming witchcraft, are only experienced by Dalit women. Apart from this, they are also threatened with rape as part of a collective punishment by the upper castes which was also evident in the recent Hathras case.

In the current scenario, where capitalist neo-liberal and new-colonial forces are spread across the globe, it is necessary that the feminist movement comes together in solidarity, while also recognising intersectional differences, so as to address the varying patterns of oppression. The way the Dalit feminist movement has drawn inspiration from the Black feminist movement is an example of how solidarities can be forged transnationally in this increasingly globalized world.

These movements inspire to reject the gap between the global and the local and urge to think globally and act locally. The epistemological and experiential viewpoint of Angela Davis of the Black woman as a racialized subject adds to her analysis of the historical oppression of Black female bodies. At the same time, it serves as a rich foundation for any such analysis that waits to be attempted by future scholars.

References:

- Davis, Angela. Women, Race and Class. 1981. Penguin, 2019

- Gramsci, Antonio. “The Formation of the Intellectuals” in Theorysims: an introduction. Edited by Bodhisattva Chattopadhyay. Worldview Publications, 2015

- Morrison, Toni. Beloved. 1987. Vintage International, 2004

Daksha Chaturvedi is a graduate in English literature and currently a student of Women’s Studies. There are hopeless romantics and then there are hopeless feminists, Daksha identifies as both and looks forward to being a researcher and a killjoy for the nasty men in academia. You may find them at daksha998@gmail.com

Featured Image Source: Datebook