Recently, an incident was reported from Palakkad, Kerala, about Rahman from the Ayiloor village of the district, revealing how he allegedly hid the woman he was in a relationship with for nearly 10 years in his house without the family’s knowledge. Sajitha, who went missing for 10 years from her maternal home allegedly lived in Rahman’s bed room for nearly a decade. The couple had eloped to Rahman’s place because they feared opposition from their parents as a result of their inter-faith love affair.

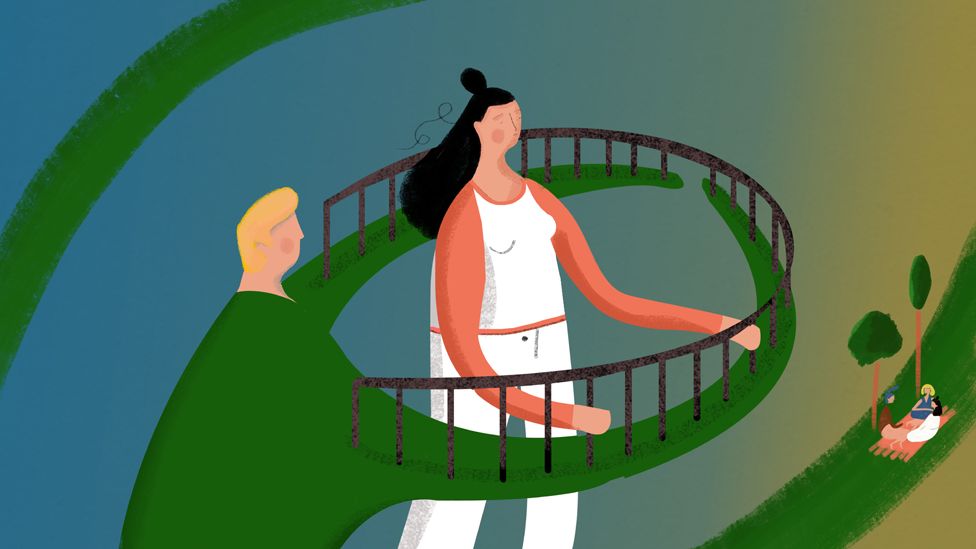

The incident calls for our acknowledgement and renegotiation of women’s agency in heterosexual romantic relationships, when in this case, Sajitha was lauded with benevolent sexism and glorified for impounding herself in a single room for nearly 10 years. The case becomes an important standpoint to investigate the ideal moulds of ‘femininity‘ in the context of romance and thereby to understand how traditional gendered behaviour is reproduced in such cases.

Sajitha’s helpless circumstances were augmented as sacrifices for ‘true-love’, which not only gender neutralizes Sajitha’s situation of being locked in a tiny room, but also coverts the fact that romantic ideals in heterosexual relationships conform with traditional gendered behaviour, where women are expected to be emotionally and physically accommodating to discomforting environment at the cost of their well-being.

The fact that Sajitha was reported to eat half of the food from Rahman’s plate during her meals as Rahman’s family was completely unaware of her presence is a symbolic one which prompts us to see through the ritualised, traditional and historical ways of performing gender in romantic or marital relationships. Thus, what is deemed as being romantic in Rahman’s case is in fact, a novel experience of romantic love and sacrifice that demands the reproduction of gendered inequalities that work to broaden power differences between heterosexual couples. One can hardly imagine the glorification of a similar narrative if the gender roles were reversed.

One might justify this as a consensual venture of the heterosexual couple, but what is neccessary to imagine is the pressure exacerbated on women in patriarchal societies like India which disallows them to reconsider their choices once they decide to elope with a man

In their report, Sajitha was seen complacent with her confining circumstances as an ordeal for ‘true love’. Her consensual stance enables us to understand that women remain embedded within a heterosexist imperative where they are constructed as equal and given the power of choice, so long as these choices conform to the imperatives of heterosexuality. The ‘paternalistic chivalry’ of Rahman where he is seen protecting Sajitha inside a small roof of a tiled house promotes the idea that men should protect and cherish women, and women should be passive, emotionally supportive and adaptable to untimely circumstances.

Alternative marriage models like elopement in most cases make women submissive and receptive to slavish ill treatment in their conjugal families, justified in the name of ‘womanhood’. Romance is seen as a point of contact between heterosexual men and women, a point of contact seen stereotypically as ‘nice’ and desirable, but also one that is desired more by women, the disenfranchised group.

Also read: Analysing Body, Autonomy & Gendered Spaces In The Great Indian Kitchen

Romance, which is an ubiquitous social product acquires its conventional connotation through various media representations. Such a notion sustains myths and unrealistic expectations about marriage and what it means to ‘live happily ever after’, the burden of which falls on women. The gender identities performed while being romantic are not neutral but are highly gendered and entrenched in idealised, old-fashioned patriarchal gender values.

Sajitha was locked in a tiny room with wooden bars on the window which could be removed when needed. According to the police, Sajitha would go out only at night and would remove the bars and jump out of the window to go to the bathroom outside the house. If she fell sick, Rahman would bring the medicines. “I had installed a TV inside the room. I would take food to the room for us to eat together,” Rahman said.

The collective idea of what romance looks like in this case – a decade of sacrifice and emotional housekeeping by living in a small room – is difficult to re-imagine or resist as a gendered production owing to how such expectations from women in heterosexual relationships are normalized. The fact that no incidents of emotional and physical abuse were reported saves Rahman from any confrontation of his patriarchal gallantry that has cost Sajitha her emotional and mental sanity, social life and independence.

She also noted that she has missed two weddings that have happened at her natal home in the last decade. Thus, being passive and at the receiving end of all the inconveniences seems integral of the broader discourse of heterosexual romantic relationships for women. Romantic femininity is void of any agency and projects one as “a woman to whom things happened”, thus glamourising female victimisation

One might justify this as a consensual venture of the heterosexual couple, but what is necessary to imagine is the pressure exacerbated on women in patriarchal societies like India which disallows them to reconsider their choices once they decide to elope with a man. Women who decide to pursue unconventional ways of marriage due to fear of opposition from family and society are character assassinated and abandoned by their natal households, making them vulnerable and compelled to live in dire conditions in their conjugal family.

Sajitha also told the media that they had to stay like that because of their situation. “He gave me half of the food he got. He took care of me very well. But it was difficult to stay in a room. During the day, I used to watch TV using a headset and walk around in the room.” She added, “When no one was there, I used to come out of the room at times. At night, I used to go out and walk, but not during daytime. I did not fall sick except for some headaches.”

She also noted that she has missed two weddings that have happened at her natal home in the last decade. Thus, being passive and at the receiving end of all the inconveniences seems integral of the broader discourse of heterosexual romantic relationships for women. Romantic femininity is void of any agency and projects one as “a woman to whom things happened”, thus glamourising female victimisation.

It was reported that the family denied all allegations of holding Sajitha captive for such a long period of time. Further, the Women’s Commission Chairperson M. C Josephine pointed out the criminal element in the case. The news of Rahman allegedly fixing a contraption on the door which ensured that the door was locked using a remote and could not be opened from outside, was reported to the village police. The Commission filed a suo moto case for blatant violation of human rights. It noted that the woman was kept as a slave in inhuman conditions.

The Chairperson decided to visit the couple after the lockdown to take cognisance of the matter, to investigate the bizarre elements of present case and also into the lapses on the part of the police in investigating the missing case of Sajitha 10 years ago. While Rahman’s family members were completely hostile to his narrative and dismissed it, they claimed that his eccentric behaviour of electrifying his room’s door with barbed wires around was because of his mental health concerns.

The case sheds light on the need to redress women’s role and agency in the complex heterosexual structure of marital and romantic relationships and renegotiate the idealised gender enactment of love and romance in the public domain. It also provides evidence of the grave repercussions of unacceptance of inter-faith marriages that can cost women their lives and well-being

Taking into consideration such claims Sajitha’s position seems worrisome and complex with respect to her relationship with Rahman, as it is likely that she was held captive in some other place and was ordained to live in unhealthy condition by her ‘ultimate‘ lover Rahman. The story narrated by Rahman sounds quite illogical and her deplorable conditions in no sense can be ‘caroused’ in the name of love. The Commission would acquire Sajitha’s statement in the legal matter.

Furthermore, the entire case is testimony of how normalised toxic patterns in heterosexual relationships harboured in the name of love are, especially among the marginalized communities. Women are impelled to meet with and be at the receiving end of larger structural problems like unemployment and are banished from their natal communities for failing to conform to traditional religious norms, embedded in a patriarchal set up. On the contrary, men remain immune to such exclusion and resort to gender violence as a coping mechanism of their mental health deterioration.

The case sheds light on the need to redress women’s role and agency in the complex heterosexual structure of marital and romantic relationships and renegotiate the idealised gender enactment of love and romance in the public domain. It also provides evidence of the grave repercussions of unacceptance of inter-faith marriages that can cost women their lives and well-being.

Also read: You Are My Soulmate Because Society Approves Us: Intersectionality In Love

Featured Image Source: BBC

About the author(s)

Mansi Bhalerao is an Ambedkarite feminist, an undergraduate at Miranda House. She is an aspiring student of Sociology, trying to navigate and assert her praxis.