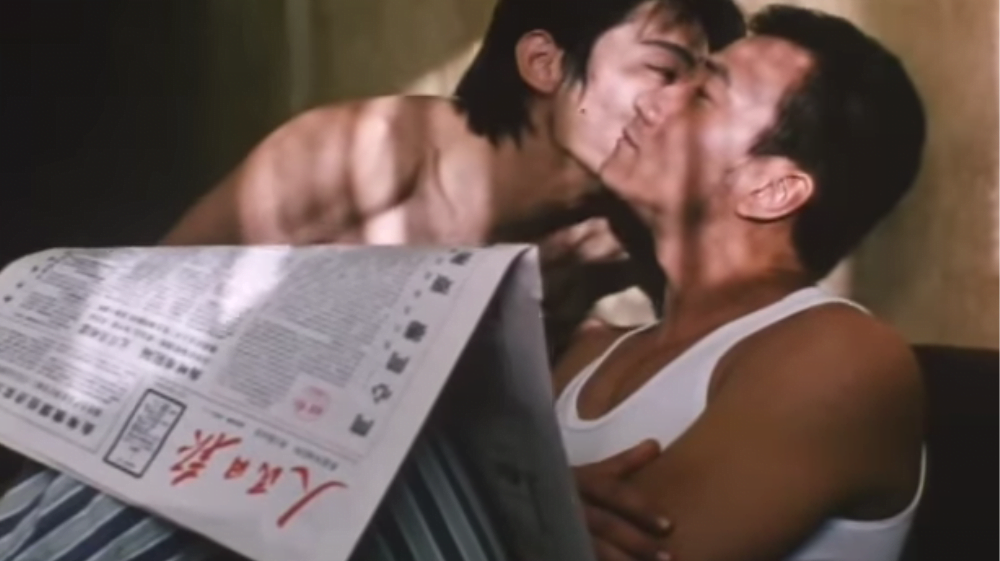

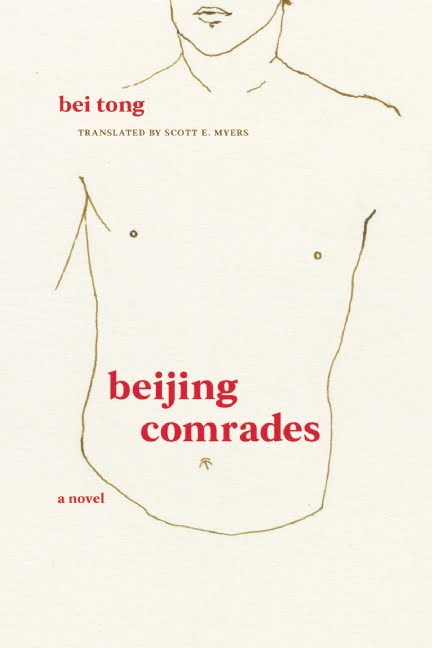

Beijing Comrades is a radical novel by Bei Tong that depicts a same-sex relation in Mainland China, and radically critiques the totalitarian government during the period of reformation of the late 80s. Narrated from the point of view of Han Dang, a wealthy businessman, the confessional novel traces sexual exploits, homosexuality, and income inequalities posed during the period of reformation, to the Tiananmen Square Massacre, and beyond.

The novel was anonymously published on an underground gay website (now defunct), known as Chinese Men’s and Boy’s Paradise, and gained a cult following because of its unwavering commitment to demystifying same-sex relations. The identity of the anonymous author, Bei Tong, has always been of wonder. Their gender, sexual orientation, and personal life experiences are often brought into question. However, the authenticity of Bei Tong’s authorial voice is evident. They wrote the novel after reading “the pornographic stories out there,” claiming that they could “write something better”. The pseudonym Bei Tong comes from the abbreviation of the word “tongzhi,” the term used by people in China to denote diverse sexual identities.

In 1978, Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping declared reforms that would shift the country out of the chaos and terror of the Cultural Revolution. One of the biggest reforms involved the de-collectivization of agriculture, which pushed people from villages to move into cities in droves. He also opened the country up for foreign investment and gave permission to entrepreneurs to start businesses. It is during the bustling era of reforms that the story of Han Dong and Lan Yu opens. Han Dong is the wealthy and spoiled offspring of former Party members, who studied Chinese literature in university, and went on to make a successful business worth millions of dollars. He is shown to use sex as a sport, with pleasure induced from both men and women.

In Han Dong’s first sexual experience with a man, he says: “I had long known it was possible for two men to do this sort of thing but I had no idea how much I would like it.” As the private sector grew under the reforms, Han Dong did well economically and bought the affections of his various lovers through many expensive dinners and gifts. He was used to treating people like sexual objects, and fulfilling their material desires in return.

The book does not focus, like most mainstream queer literature, on the act of “coming out.” Although it candidly inculcates the homoerotic in the narrative, the characters are not interested in attaching a specific sexual identity to themselves. The central narrative is a love-story set in Beijing, and the complete rejection of conformity to a static sexual orientation is what makes the novel unlike any other in its genre. Sexual acts are rarely accompanied by euphemism, and depictions of internalized misogyny and homophobia, even within the homoerotic Han Dong, are not removed; revealing the three-dimensionality of a man at the cusp of modernity. Beijing Comrades is liberating and unapologetic, and the captivating erotic scenes are tastefully translated by Scott E. Myers.

Also read: Book Review: Jorasanko—A Semi-Fictional History Of The Tagore Women

Han Dong is in his late-twenties when he meets Lan Yu, and is moved by the cold indifference of a guy who has so little. Lan Yu is described as, “your typical Communist Youth League hopeful from the provinces.” Han Dong is introduced to Lan Yu by his close friend and business associate, Liu Zheng, who often scouts for potential lovers for his boss. Lan Yu had the impoverished look of a man who would sell his virginity for a few bucks. However, he is not depicted like a hungry beggar devoid of dignity, nor as a victim of poverty and family strife, but just as a simple sixteen-year-old enrolled in architecture school who wants to be successful. He is offered a thousand yuan upon sleeping with Han Dong, but he only takes half the money as a loan. In the afterword, Professor Petrus Liu talks about the significance of this particular exchange of money.

By constructing Lan Yu as a figure of true love who, despite his background as an impoverished migrant, remains utterly uninterested in monetary gain, the novel appeals to contemporary Beijing gay men’s prevalent fear of being associated with or, worse still, mistaken for “money boys.”

Throughout their relationship, the question of money is pertinent. Lan Yu refuses to take Han Dong’s money, and if he ever does, he always takes it as a loan. As Han Dong is forced to confront his gay identity, he is also forced to reconfigure relationships outside of the give-and-take system he has devised as the norm. The anxiety surrounding the pair’s unequal status is evident; people refer to Lan Yu as Han Dong’s “concubine” but Lan Yu is undeterred in his refusal to monetary help. Han Dong gifts him a car, clothes, and an entire apartment. But Lan Yu eventually uses these possessions to rescue Han Dong from jail.

The question of homosexuality rests in a liminal space for Han Dong, who thinks of a lifelong romance between two men as unnatural. His eventual plans always include having a wife and kids; his primary filial duty lies in being a “normal” son. No matter how palpable his devotion to Lan Yu, a man ten years his junior, he always informs him that their relationship would be ephemeral, and that they would only stay together till it’s right.

Although Lan Yu and I entered into a new period of stability in our relationship, I didn’t completely stop sleeping with women. I went to bed with them not because of any physiological need; nor even because I liked them, but because of a need that was completely psychological. I wanted to prove to myself that I was a normal man.

Although he does not outrightly condemn homosexuality or his desire, he also does not succumb to it or solidify his queer identity. He is shown to be equally attracted to women. It is unclear whether he loses interest in women after a while because he is inherently a playboy, or whether he can’t sustain an interest in the female body. At one point, Lan Yu mentions that Han Dong is lucky to be attracted to both men and women, claiming it is much simpler for him. Although Lan Yu never outrightly refers to himself as a gay man, he affirms a future without marriage and children. However, it is not a lack of identity, but the lack of conformity to a sexual identity that constitutes a bulk of his character.

Also read: Book Review: The Scarlet Letter By Nathaniel Hawthorne

Han Dong tries to get Lan Yu into conversion therapy to cure him of his perverse illness, believing that Lan Yu views himself as a woman, whereas he himself is only occasionally attracted to men. Their dynamic is fraught with an income inequality, and Lan Yu is often shown as submissive, wearing his hair the way Han Dong desires, and even going into therapy to please him. However, Lan Yu isn’t devoid of a voice, both economic and emotional. He establishes his financial independence by working jobs that Han Dong disapproves of, and never accepts money as a reward. Lan Yu refuses to be emotionally manipulated. Their on-again, off-again dynamic constitutes complete independence on the part of Lan Yu, who despite his economic and social disadvantage, does not call out to Han Dong for help. While Han Dong is shown to have the shrewd sense of a businessman, Lan Yu is shown as empathetic and emotionally mature.

In present-day China, identification with the word “homosexual” is loaded with social condemnation. Although consensual homosexuality was legalised in 1997, and homosexuality was removed from the Chinese Society of Psychiatry’s list of mental illnesses in 2001, there are no civil rights laws to address discrimination or harassment. Gay conversion therapy is not banned nationwide and continues to be practiced. While Beijing Comrades covers “unchartered territory in Chinese queer writing,” it continues to thrive because of its universal themes of love, loss, and longing – proving to be an addictive read. Beijing Comrades is exceptional because of the absence of labels regarding sexual orientation and an unpredictable, page-turning, narrative.

References

- Tong, B., Liu, P., & Myers, S. E. (2016). Beijing Comrades. The Feminist Press at CUNY. Here is a link to the book.

- Garnaut, R., Song, L., Cai, F., & Chow, G. C. (2018). In China’s 40 years of reform and development: 1978-2018 (pp. 93–115). essay, ANU Press.

- Sparks, H. (2021, March 2). Homosexuality can be called a mental disorder, rules Chinese court. New York Post.

Suhasini Patni is an English and Creative Writing graduate from Ashoka University. In 2019, she graduated summa cum laude from the Ashoka Scholar’s Programme and since then she’s worked as a teaching fellow, and visiting faculty at Nirma University. Her writing was short-listed for the Toto Funds the Arts, Creative Writing in English award, 2021. She’s a freelance writer at scroll.in and her work has appeared in Asymptote, The Tishman Review, and elsewhere.

Featured Image Source: Osu.edu