The same injured vice lives in our grandmothers, mothers, mothers-in-law, teachers, aunties, sisters, friends and within each of us.

M.C. Josephine is an activist and politician who recently stepped down from the position of Chairperson of Kerala Women’s Commission, in the wake of public outrage over her response to a victim of domestic violence on TV during a live phone-in programme.

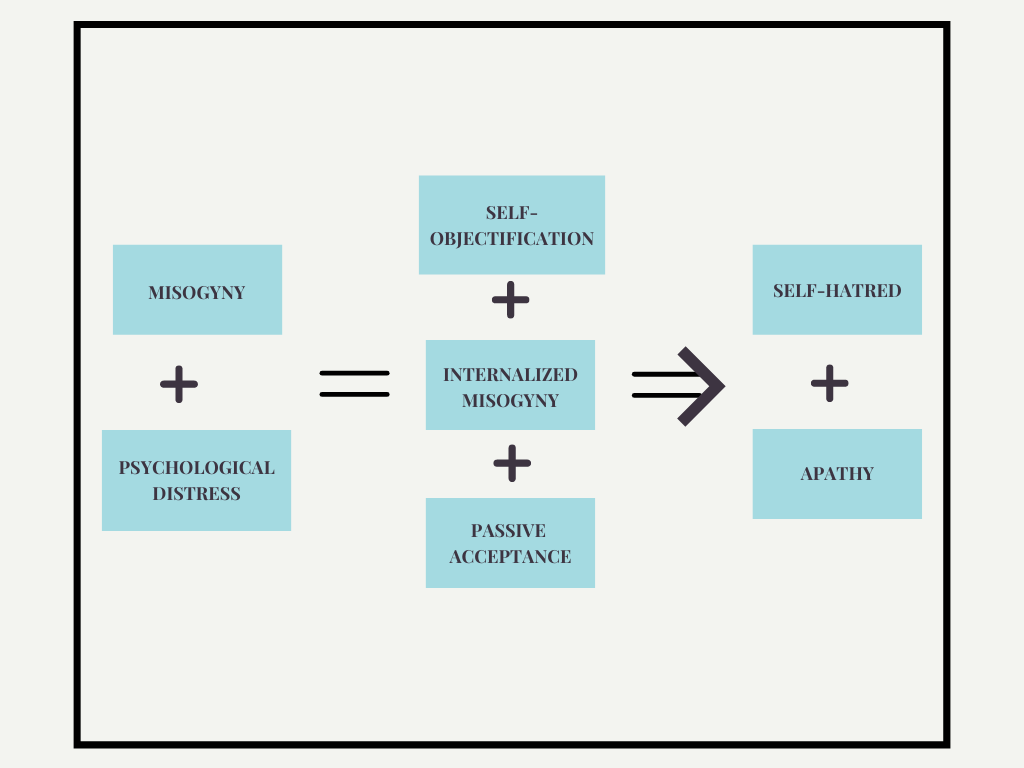

The pain invoked by M.C.Josephine’s words is neither about ‘language orthodoxy’ nor a reaction to the theme of Oppression Olympics she seemed to use while prematurely disqualifying the victim’s right to grieve. Describing the problem as her ‘insensitivity’, ‘rudeness’ and ‘the irritability of tone’ minimises the endemic of internalised misogyny.

M.C. Josephine’s antipathy towards the victim invalidated the victim’s suffering. Her deflection of the blame towards the victim for not having initiated legal action against the perpetrator is not a mere blind eye to the victim’s possibly compromised safety, codependency, trauma bonding, fear, shame and other situational or emotional factors, not to mention the terrifying stories of negligent responses from the police that we have heard from other victims. But her reaction carries depths of victim-blaming and gaslighting, further reaffirming any victim’s worst nightmare– of not being heard, seen or believed when they speak their truth.

The self-hatred of internalised misogyny is a failed and misplaced resistance. An anger that had forgotten its enemy seeped into oneself and blazed fire at one’s own femininity– ‘the curse’ that attracts patriarchal abuse. It burned into ashes the ‘messiness’ of the recklessly feminised emotion called empathy. Does M.C. Josephine’s internalised misogyny deserve sympathy just as much as it needs accountability? There is no room to empathise with the bully and the vile abuser in M.C. Josephine, but it is important to see its roots.

The pain invoked by M.C.Josephine’s words is neither about ‘language orthodoxy’ nor a reaction to the theme of Oppression Olympics she seemed to use while prematurely disqualifying the victim’s right to grieve. Describing the problem as her ‘insensitivity’, ‘rudeness’ and ‘the irritability of tone’ minimises the endemic of internalised misogyny.

Also read: What The Case Of Vismaya & Surging ‘Dowry Deaths’ In Kerala Tell Us

We all know women like M.C.Josephine. She starts playing the game of respectability politics by agreeing with misogyny’s demands, just enough to be heard and seen by men. Then she submits her own authenticity to get a seat at the table. She further betrays other women’s interests to sustain the approval of a heavily masculine political public with a pathetically delicate male ego. She climbs on the monster’s shoulder to get to the top of the mountain until she forgets the rules of discretion, exposing her allyship with misogyny. The shoulder disappears. All fingers point to her and the limelight of monstrosity shifts to shine brightly on her face.

The radicalised and casteised femininity of Kerala women is rendered invisible and colonially muted to fit to the role of less-than-human other, the opposite to the dominating knowing-subject who is the epitome of reason and knowledge– first the Aryan Brahmin Masculinised subject, then the Westernised Masculinised White subject, now a faceless misogynist with many shadows take the centre stage while the Brahmin man and the White man continue to fill their pockets and gain social capital behind that stage. The inherited trauma and unhealed victimhood of Kerala’s faceless misogynists hide in the gnarled tentacles of castes, economic classes and genders. The perpetual reproduction of this duality produces ever-lasting, ever-deepening profound injuries in the cognition alongside the intergenerational collective trauma.

The trauma responses can look like internalised subordination, lack of self-worth, disassociation, distorted sense of agency and self determination, denial etc. These aren’t signs of weakness but an array of exquisitely self-harming coping mechanisms, a refusal to be buried alive.

Unfortunately, this coping mechanism injures not only oneself but the parts of themselves they see around them– like M.C. Josephine bullying the part of herself that she sees in the helplessness of domestic violence victims. M.C Josephine’s shockingly callous apathy is a projection of her desensitisation from pain, denial, dissociation and emptiness. Her shame in her sense of self as a woman is projected onto other women, wrapped in a tone of contempt and despise, blocking the victim’s blood from seeping onto her political image and between the ornate embellishments of the system that failed to protect the victim. Her attempt to intimidate the caller by instilling fear is the stale hack of every insecure, self-hating bully.

Internalised misogyny in women is the unhealed injury that devalues and distrusts other women while applauding male domination because they are addicted to the familiar patterns of trauma responses.

Are we cancelling M.C. Josephine?

Activism lives in the unseen body of water between the binaries of the ‘good’ and the ‘bad’ that sparkles in the light of self-enquiry, knowledge, self-reflection and accountability. Activism, revolution and social justice movements are testaments to our hope and optimism in that water flowing bountifully, breathing love into life. That potential to flow and transform is what makes us human beings. M.C. Josephine, has the same potential to consciously learn, carefully unlearn, heal and love like any one of us.

This is also a moment for us to reflect on the innumerable chances we, as a society, offer men when they shed tears in public and feign an apology with no accountability nor changed behaviour. This is the same society that ostracises women who retaliate to misogyny and sentences women to lifelong banishment for calling out the many hypocrisies of male domination. The same society that rewards women for internalising misogyny and conforming– offers women a shoulder to climb on if she’s willing to betray her authenticity and other women’s interest. Yes, unsurprisingly, the very same society is also eager to banish and cancel a woman who internalised and displayed a little too much of the same misogyny that dehumanised her because everything’s fair in patriarchy’s game of respectability politics.

Unsurprisingly, the very same society is also eager to banish and cancel a woman who internalised and displayed a little too much of the same misogyny that dehumanised her because everything’s fair in patriarchy’s game of respectability politics.

Also read: A 101 Introduction To Internalised Misogyny

The many shadows of M.C. Josephine’s internalised misogyny doesn’t cease to exist with her resignation. The same injured vice of coping mechanism that sabotages the interest of womanhood lives in:

● the grandmother who wouldn’t hug her menstruating granddaughter before going to the temple,

● the mother who dutifully trains her daughter to not talk back,

● the sister who teases her brother when he cries,

● the wife who is disappointed that her husband is not career-driven,

● the teacher who ask the girls on the front row to sit with their legs closed,

● the cousin who lovingly offers weight loss tips at weddings,

● the roommate who advises her girlfriend to forgive the verbally abusive fiancée,

● the auntie who proudly offers tips to the bride on becoming ‘an adjusting wife’,

● the mother-in-law who wants her daughter-in-law to take more time off from work than her son to care for her grandchildren

and the list goes on.

The vice has been planted in each one of us and that works in favour of the forces in power so no one will urge us to reflect on it. We are not and will never be the true benefactors of patriarchy no matter how persuasive our shadows can be.

Featured image source: Sanu N/Wikimedia Commons

This is exactly what I was thinking. The lady is still arguing about what was wrong in what she said. This kind of behavior is prevalent not only in Kerala but also in other parts of India. I guess we will have to tolerate the slow change.